First Native American Navy Pilot

Long-time Arlington resident Thomas Oxendine became the first Native American Navy pilot when he enlisted in 1942 following the attack on Pearl Harbor and U.S. entrance into World War II. His distinguished Navy career would bring him to Arlington in 1965 to work at the Pentagon and, later, for the Bureau of Indian Affairs during a period of intense American Indian activism in the 1970s. In 2007, he discussed his fascinating life and career in an oral history interview with the Center for Local History.

Please note that the phrases “Native American,” “Native,” “American Indian,” and “Indian” are used interchangeably in this blog post. This is aligned with Oxendine’s own use of these phrases, and accounts for the names of organizations and movements that use various terms of identity. For further information, see this guide on terminology prepared by the National Museum of the American Indian.

A young Thomas Oxendine. From the University of North Carolina at Pembroke Indianhead Volume 66, p. 221.

A Lumbee Indian from North Carolina, Thomas (“Tom”) Oxendine was born in 1922 in a small village west of Pembroke. The oldest of eight children, he learned to read and write before he started school at the age of 5, leading him to graduate from Cherokee Indian Normal High School when he was only 15.

He enrolled in Cherokee Normal College (now called the University of North Carolina at Pembroke) to pursue a Bachelor of Arts in education, where he began taking flight courses in a civilian pilot training program funded by aviator Horace Barnes. Despite the U.S. military’s official policy of racial segregation, Barnes had petitioned the government to train ten Native Americans to fly through a program similar to the Black pilot training program that operated out of Tuskegee University.

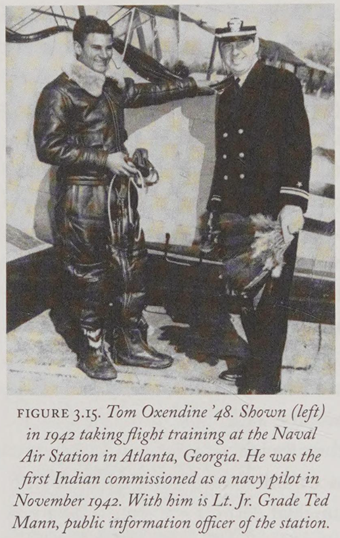

Oxendine in flight training. From Hail to UNCP!: A 125-year History of the University of North Carolina at Pembroke, p. 102.

Through this three-month course, Oxendine earned his private pilot license at 18, and in 1942 he attempted to enlist in the Navy. At that time, the Navy restricted American Indians from becoming officers. However, to address the Navy’s wartime needs, an exception was made that allowed Oxendine to participate in Navy flight training.

Oxendine built an illustrious career as a Navy pilot, taking part in 33 battles during World War II and earning many medals. This includes the Distinguished Flying Cross, which he was awarded for risking his life to rescue another soldier while under gunfire on Yap Island in 1944 (an excerpt of Oxendine’s interview where he recalls the rescue mission here).

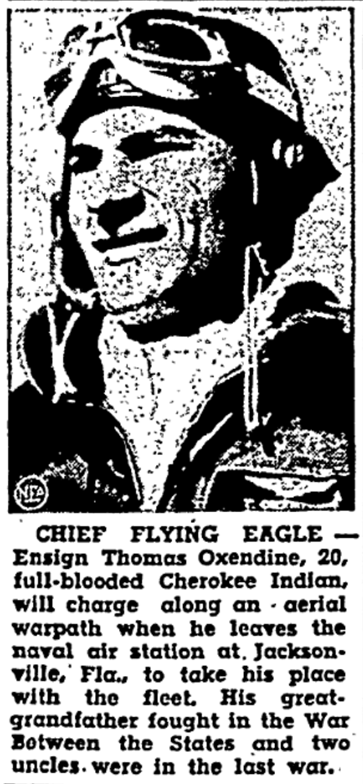

Oxendine received widespread press coverage as the first American Indian Navy pilot. Here, the reporter refers to him as a Cherokee Indian because the Lumbee were at that time part of the National Congress of American Indians under the name “Cherokee Indians of Robeson County.” In 1952, the tribe voted to adopt the name “Lumbee.” From The Flint Journal, December 25, 1942, p. 18.

In 1965, after retiring from two decades of flying, Oxendine received orders to relocate for an assignment at the Pentagon with the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations in the Plans Division. As Oxendine prepared to move to Arlington, he received some good advice from a Navy Captain, including how to avoid the dreaded traffic jams on Shirley Highway:

OXENDINE: ...At the end of my career in flying I was assigned as a Deputy Fleet Information Officer at US Pacific Fleet where we put out all of the press releases for what’s going on out in the Pacific. At the end of that tour, I was ordered back for duty at the Pentagon. Never having served in the Pentagon here in Washington, some time a lot of aviators tend to try to avoid that. So, I was in my seventeenth year or so. I received orders to OPNAV [Office of the Chief of Naval Operations] in the Plans Division for contingency planning.

A Navy Captain said: "Ox, I have some good advice for you. Don’t rush back there and try to find a place before the packers so they don’t have to store your goods. Go back, take a month or two, Arna Valley or some place, let them store your things and take your own time about where you want to live because too many people rush back and make quick decisions and then regret that decision the length of time they’re in Arlington.” That was his first bit of advice. Second bit of advice he gave me was: don’t live anywhere where you have to use that Shirley Highway to get to the Pentagon, which is now 395. It was just a four-lane drive at that time. He said twice a day that is a parking lot. The third thing is: " Don’t live anywhere where you have to cross a bridge to get to the Pentagon."

So, putting that all together wind up coming into Arlington and I wound up at 1141 North Harrison Street and I’ve been very happy there. I made that decision. Four miles from the Pentagon and never any problems of commuting.

Oxendine’s home at 1141 North Harrison, where he lived for 45 years with his wife, Elizabeth Moody Oxendine, and their three sons.

After moving to Arlington, Oxendine became an aviation plans officer for the Office of Information in the Secretary of Defense, then headed the public affairs unit for the Naval Air Systems Command located in Crystal City. In 1970, Oxendine retired from the Navy to become head of the Public Information Office at the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), a position he held for 17 years.

He joined the BIA at a particularly contentious time, as the Red Power Movement ushered in a new age of American Indian activism and increased demands for Indian self-determination. Oxendine’s expertise was sought out under the direction of Commissioner of Indian Affairs Louis R. Bruce Jr., a Mohawk who pushed for the recruitment of Indians to head BIA activities and create policies that could better serve federally recognized tribes.

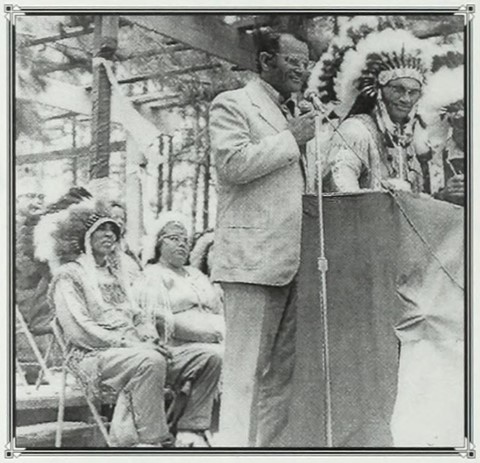

Tom Oxendine and Chief W. R. Richardson of the Haliwa-Saponi speaking at one of that tribe's powwows in the 1970s. From the Fall, 2005, edition of Tar Heel Junior Historian: North Carolina History for Students.

Despite these efforts to restructure the BIA, many Indians involved in the Red Power Movement regarded the organization with wariness and distrust due to its long history of disenfranchising Native Americans while erasing Native culture and language through its infamous Indian boarding schools.

Two years into Oxendine’s BIA tenure, hundreds of Native American activists took part in “The Trail of Broken Treaties,” caravanning across the nation toward D.C. to demand a meeting with President Nixon and deliver their Twenty-Point Position Paper, aiming to assert the sovereignty of the Indian Nations and reopen treaty negotiations.

When they arrived on November 1, 1972, protestors were denied this meeting and found themselves lacking adequate housing. While attempting to arrange for temporary shelter in the BIA building, conflict erupted as guards tried to forcibly remove protestors, who refused to leave, barricading themselves in.

By the end of their six-day siege, protestors had taken possession of many BIA files that they claimed as evidence of corruption and scandal within the BIA, as well as Native artwork and cultural objects that they regarded as rightfully theirs.

The Trail of Broken Treaties was only the beginning of a decade of intense American Indian activism, including the Wounded Knee Occupation, the 1976 Trail of Self-Determination, and The Longest Walk in 1978.

The 1973 Wounded Knee Occupation in South Dakota received wide press coverage, and Oxendine conducted many of the twice-daily press briefings of the protest, handling international journalists as well as dozens of American TV crews, newspaper reporters, wire-service representatives, magazine writers, and members of the Indian and underground press.

While working for the BIA, Oxendine became involved in the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI), an American Indian and Alaska Native rights organization founded to represent Native tribes and to resist federal pressure for termination of tribal rights and cultural assimilation.

NCAI provided support and advocacy for Nixon’s proposed policy of American Indian self-determination, which was passed in 1975 as Public Law 638, the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act.

The act expanded tribal authority over the administration of federal funding and reversed a 30-year effort by the federal government to sever treaty relationships with and obligations to Indian tribes. Oxendine also became a member of the National Aviation Club and was one of the first American Indians to be admitted to the National Press Club in D.C.

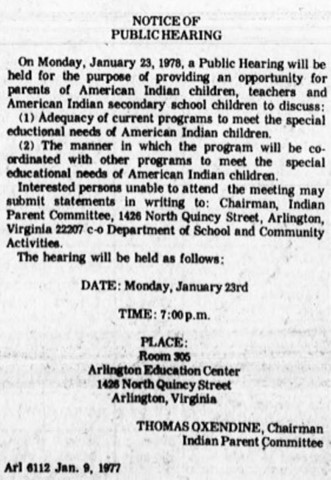

At home in Arlington, he served as chair of the Indian Parent Committee, collaborating with the Arlington school system to address the specific needs of American Indian children.

Notice for a Public Hearing held by the Indian Parent Committee on January 23, 1978, inviting parents, teachers, and students alike to discuss how Arlington schools could better address the needs of American Indian children. Northern Virginia Sun, vol. 41, no. 6, January 9, 1978.

After retiring from his role as a public information officer, Oxendine was sought out by the Census Bureau to promote the participation of Native Americans and Alaska Natives in the count. He also worked for a consulting firm overseeing agreements between Native tribes and companies seeking to do business on reservations.

In his work, Oxendine valued transparency and clarity around the relationship between Native Americans and the United States government, viewing knowledge as a tool that American Indians could use to advocate for themselves and their tribes.

Throughout his lengthy career, Oxendine took responsibility for sharing the truth, no matter how difficult that truth may be. He often sought guidance from one of the great lessons he learned in his college philosophy class: “Truth is good, it’s the lack of information where the problems are.”

Thomas Oxendine passed away on May 27, 2010, at his home in Arlington. Although many remember him as a hero for his service in World War II, he left behind an equally impressive legacy advocating for Native American rights.

You can find Thomas Oxendine’s interview in its entirety in the Center for Local History – VA 975.5295 A7243oh ser.3 no.207.

Further Reading:

Lakota Woman It is a memoir by Mary Brave Bird, a Sicangu Lakota formerly known as Mary Crow Dog. In it, she describes her participation in the 1972 Trail of Broken Treaties and the 1973 Indian Occupation at Wounded Knee. For other recommendations, see the Native American Voices Book List.

Works Cited:

Baker, Donald P. "U.S. Accused of Exhibiting BIA Damage: U.S. Accused of Showing BIA Damage." The Washington Post, Times Herald, November 23, 1972.

Blair, William M. "Shake-up Pressed at Indian Bureau: A Dominant Role for Indians Is Aim of Reorganization." New York Times, December 9, 1971, p. 29.

"Chief Flying Eagle." The Flint (MI) Journal, December 25, 1942, p. 18.

Eliades, David K., Thomas T. Locklear, and Linda E. Oxendine. Hail to UNCP!: A 125-year History of the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. University of North Carolina, 2014.

Horton, Paul B. Readings in the Sociology of Social Problems, 2nd ed. (Prentice-Hall, 1975), p. 299.

National Parks Service. The Struggle for Sovereignty: American Indian Activism in the Nation’s Capital, 1968-1978.

Neufeld, William. Slingshot Warbirds: World War II U.S. Navy Scout-Observation Airmen. 2003.

North Carolina Museum of History. Tar Heel Junior Historian: North Carolina History for Students. Fall, 2005.

The Northern Virginia Sun, vol. 41, no. 6, January 9, 1978.

Obituary for Thomas Oxendine, The Robesonian, May 29, 2010.

The University of Florida Department of History. Interview with Thomas Oxendine, November 6, 1974.

The University of North Carolina at Pembroke. The Indianhead, vol. 66. 2011.

Help Build Arlington's Community History

The Center for Local History (CLH) collects, preserves, and shares resources that illustrate Arlington County’s history, diversity and communities. Learn how you can play an active role in documenting Arlington's history by donating physical and/or digital materials for the Center for Local History’s permanent collection.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields