One Community’s Evolution

African American history is not a separate component of the Arlington story, but a central part of our shared history.”

-- John Paul Liebertz, “A Guide to the African American Heritage of Arlington County Virginia,” Second Edition, 2016

Part 1: Freedman’s Village

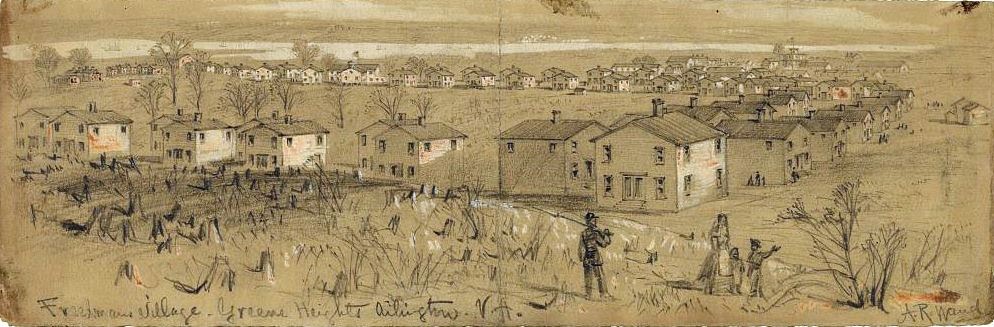

On property that today houses the Pentagon and Arlington National Cemetery, a little-known, thriving, African-American community called Freedman’s Village once stood.

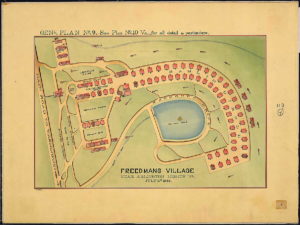

Established and formally dedicated by the U.S. Government in 1863, Freedman’s Village was located on land that surrounds Arlington House, a sprawling antebellum plantation inherited by Robert E. Lee’s wife, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, and where the Lee family lived for a number of years. The main objective of the founding of Freedman’s Village was to provide protection, education, instruction, and employment to its African-American residents.

Situations were at times far from ideal, but Freedman's Village quickly gained a reputation as a haven for “contraband” (escaped slaves) and freepersons due to its rural location, away from the crowded, diseased-ridden city camps in Washington, D.C. , where individuals were less likely to survive. Camp life and living conditions were far from perfect however, and during the early years treatment of residents was questionable. Once this was exposed and an investigation was launched, conditions began to slowly improve.

As time progressed, the residents began to cultivate, improve, and create a community they could call home. Although initially planned as temporary housing, through decades of hard work and communal dedication on behalf of the residents, Freedman’s Village transformed into a developing community, a home, and a place for growth and personal success for many fugitive slaves and freepersons alike who previously had no opportunities or rights in Virginia.

During its various stages of growth and development, Freedman’s Village offered educational, professional, and emotional support for its increasing population. Residents could acquire employable skills, and many found that they finally had access to medical care, clothing, healthy foods, and adequate shelter.

Revelation and Realization of Citizenship

Along with gaining access to better living conditions, the residents of Freedman’s Village were also learning about their basic human rights as U.S. citizens. The village became an area for revelation and realizations.

Along with gaining access to better living conditions, the residents of Freedman’s Village were also learning about their basic human rights as U.S. citizens. The village became an area for revelation and realizations.

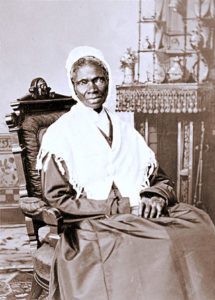

One well-known abolitionist, Sojourner Truth, resided in Freedman’s Village for approximately a year, and worked to assist villagers with access to information. During that time, Sojourner Truth worked for the National Freedman’s Relief Association. She counseled the villagers on self-care and self-maintenance, instructed the women in domestic chores, preached the gospel, helped find work for the unemployed, and taught residents how to demand their basic human rights be represented and respected.

Closing Freedman's Village

The population of Freedman’s Village fluctuated continuously, much like any temporary housing community. When it first began in 1863, it was estimated that approximately 1,000 individuals resided in the community. By July 1867, 837 inhabitants were recorded as living in Freedman’s Village. However due to its better-than-average living conditions, and its ability to offer employment and personal support to individuals, the community remained unusually strong for almost 40 years.

The Government attempted to close the village on several occasions. With each looming shutdown, the residents rallied and successfully resisted closure - until 1900, when the Government finally succeeded in closing the village permanently, and payed off residents to vacate the area once and for all.

Part 2: Queen City

Building in East Arlington

As Freedman’s Village began to decline - and especially after it was closed in 1900 - residents of the Village had to find new places to live. One such area was the nearby community known as East Arlington. Within East Arlington, two acres of land were purchased by the Mount Olive Baptist Church and this subdivision soon became known as Queen City. Located in the northern corner of East Arlington, the homes in the first wave of residency were built by African American owners.

Residents of Queen City created a close-knit community, with men usually working at the nearby brickyards (they could use the Queen City trolley stop to get to work), and women bringing in work such as sewing. Children went to school locally at the Jefferson School on Columbia Pike, and families would attend Mt. Olive or one of the other nearby churches, St. John’s Baptist or Mt. Zion. The local Odd Fellows had annual “Entertainments” at Christmas and the Fourth of July, supported community members in distress, and even made loans.

Queen City was a strong community built on proximity, hard work, social ties, and the realities of Jim Crow. The 1940 census records show 903 people living in 218 residences in the whole of East Arlington.

World War II and Eminent Domain

With the US’s entry in to World War II, the War Department needed to expand. There was no room in Washington, DC, for a building big enough to hold the department, so a new site was selected across the river in Arlington. The building, now known as the Pentagon, was on the land of the outdated Hoover Airport and the federal experimental farm, but additional space would be needed for parking and roads serving the complex. The East Arlington neighborhood - and Queen City within it - was in the way.

The federal government exercised eminent domain to take over the land in February of 1942. Homeowners were compensated, but unlike the nearby African-American neighborhood of Johnson’s Hill, Queen City did not have paved streets or running water, so property values were lower.

Casualty of Change

Residents were given four to six weeks to leave their homes in an already tight housing market, and African Americans had even fewer housing options than whites. With intervention from Eleanor Roosevelt and the House Military Affairs Committee, temporary trailer park housing was finally set up for residents in nearby Green Valley and Johnson’s Hill - but not before many families lost all their possessions because they had no safe place to store them.

Not all East Arlington residents moved into the trailers. Some moved away, a few had the money to build a new house in Arlington, and some lived with relatives. The biggest casualty was the community as a whole. Interviews with residents who lived through this time talk about the pain and uncertainty the entire community felt. Those strong community ties were diminished, and were mourned by residents for decades afterwards.

To learn more about Freedman's Village, Queen City, and all things Arlington, please visit the Center for Local History at the Arlington Central Library where you can browse our collection of books and articles on African American Heritage in Arlington County.

Read more articles on Arlington's history on the Center for Local History Blog.

For more information regarding the materials and collections available for research, please contact the Center for Local History at 703-228-5966.

thanks so much sharing this wonderful piece of history.is it available in book form?