October 23, 1850

Celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with stories about the people and events that led to the passage of women’s suffrage in the United States.

On October 23, 1850, the first National Woman’s Rights Convention began in Worcester, Massachusetts. Amidst the ringing fervor of the mid-19th-century clarion call for expanding women’s rights – with the right to vote as its central tenet – this day would emerge as a significant step in solidifying the goals and action plan of the women’s suffrage movement in the United States.

Held over two days in Worcester, Massachusetts, the 1850 Woman’s Rights Convention was planned by members of the Anti-Slavery Society, among them Lucy Stone, Abby Kelley Foster, Paulina Wright Davis and Harriot Kezia Hunt.

Davis – a New York suffrage advocate who helped petition for the passage of the Married Women’s Property Act of 1848 – would later be elected president of the convention during the event’s proceedings.

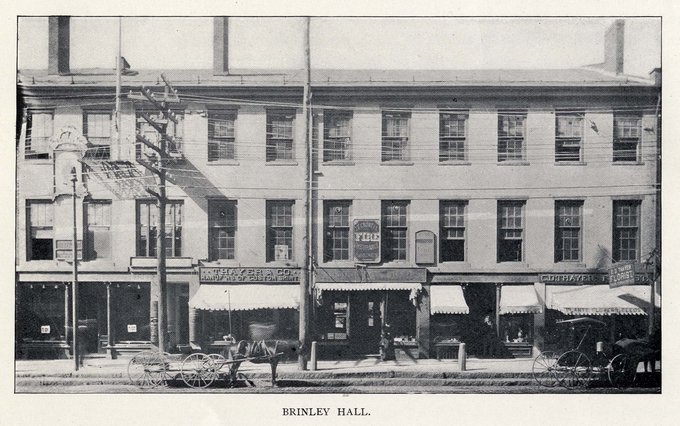

More than 1,000 delegates from 11 states gathered in Worcester’s Brinley Hall for numerous speeches on topics ranging from the right to vote, owning property, and women’s admittance to the fields of higher education, medicine, and the ministry.

Brinley Hall, Worcester, MA, where the National Woman’s Convention was held in 1850 and 1851. Photo from the Massachusetts State Library.

Among the convention’s attendees were Frederick Douglass, William Lloyd Garrison, and Sojourner Truth. Truth and many other prominent suffragists, including Ernestine Rose, Antoinette Brown and Lucretia Mott, delivered speeches over the course of the convention.

The press was largely derisive in its reporting on the convention. The New York Herald, for instance, attacked the speakers’ appearances and portrayed the attendees' demands as ridiculous, framing the convention in their headlines as an “Awful combination of socialism, abolitionism and infidelity. The Pantalettes striking for the Pantaloons. Bible and Constitution Repudiated.”

In a satirical take, the newspaper reported that the Woman’s Rights Convention organizers aimed to:

- abolish the Bible

- abolish the constitution and the laws of the land

- reorganize society upon a social platform of perfect equality in all things, of sexes and colors

- establish the most free and miscellaneous amalgamation of sexes and colors

- elect Abby Kelley Foster President of the United States and Lucretia Mott Commander-in-chief-of the Army

- cut throats ad libitum

- abolish the gallows

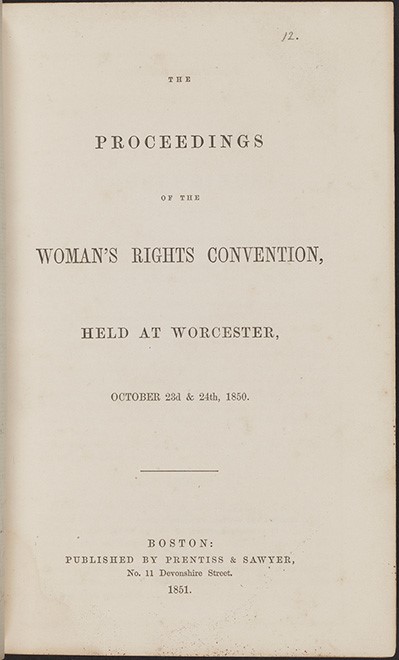

In some ways, this condescending portrayal helped expand the notoriety and message of the convention. The convention’s proceedings were recorded and sold after the event as pamphlets, gaining international readers and recognition.

The Proceedings of the Woman’s Rights Convention, held at Worcester, October 23d & 24th, 1850. Boston: Prentiss & Sawyer, 1851. Source: NAWSA Collection, Rare Book and Special Collections Division, Library of Congress (014.00.00)

The British writer and women’s rights advocate Harriet Taylor Mill was significantly inspired by the events of the convention, referencing the organizer’s work in her 1851 piece “The Enfranchisement of Women.”

The 1850 convention would be the first of many national events that would occur annually from this point forward for about a decade, setting a precedent for national suffrage organizing.

The twelfth and final Woman’s Rights Convention would be held in 1869 in Washington, D.C. This would be the last meeting of an organized suffrage front: later in 1869, the movement would split into two groups, divided by the issue of suffrage for other disenfranchised populations.

Under the leadership of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, the National Woman Suffrage Association directly opposed the 14th and 15th Amendments that would have allowed for African-American men to vote. Lucy Stone and others would go on to form the American Woman Suffrage Association, which supported the 15th Amendment. The suffrage movement would not see widespread unification again until 1890 with the establishment of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, bringing together Stanton, Anthony, Stone, Howe and other suffrage leaders, including Alice Paul and Mary Church Terrell. The group would hold its first convention in 1890 in Washington, D.C.

The 1850 National Woman’s Suffrage Convention represents a historic moment in the suffrage cause, on both scale and in terms of what resulted from the meeting. Although large suffrage conventions had been held in the past – most notably, the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention in New York -- this was the first time a convention of its sort was held on a national level.

This event set an organizing precedent within the suffrage movement for decades to come.

Learn more in “Women’s Suffrage in America: An Eyewitness History” by Elizabeth Frost-Knappman and Kathryn Cullen-DuPont, available at the Library.

2020 marked the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States.