November 14, 1917

Celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with stories about the people and events that led to the passage of women’s suffrage in the United States.

Just over 100 years ago this week, on November 14, 1917, a group of suffragists underwent a horrifying night of torture and abuse that would come to be known as the “Night of Terror.”

33 women protesters were taken to the Occoquan Workhouse in Fairfax County and subjected to brutal treatment by the prison’s guards in retaliation for the women’s ongoing peaceful protest for the right to vote.

Some of the picket line on Nov. 10, 1917. Left to right: Mrs. Catherine Martinette, Eagle Grove, Iowa. Mrs. William Kent, Kentfield, California. Miss Mary Bartlett Dixon, Easton, Md. Mrs. C.T. Robertson, Salt Lake City, Utah. Miss Cora Week, New York City. Miss Amy Ju[e]ngling, Buffalo, N.Y. Miss Ha. Harris & Ewing, Washington, D.C. (Photographer). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The arrest and imprisonment of the women was the culmination of months of organized protest. In response to the reelection of Woodrow Wilson, members of the National Woman’s Party (sometimes referred to as the “Silent Sentinels”) picketed for months outside of the White House. Bolstered by banners, signs, and a consistent physical presence, they called for the president to back a federal amendment granting women the right to vote (by 1917, nine U.S. states had extended voting rights to women).

The protests – carried out on a rotating basis to ensure a constant presence at the White House - had gone smoothly following their start after Wilson’s reelection. Wilson had even invited protesters inside the White House for coffee, although the invitation was declined.

But the mood changed after the U.S. entry into World War I, on April 6, 1917. The heightened patriotic fervor made criticism of the government more and more fraught, and members of the suffrage movement suffered for their outspoken and visible criticism of the president.

Policewoman arrests Florence Youmans of Minnesota and Annie Arniel (center) of Delaware for refusing to give up their banners. June 1917. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Helena Hill Weed, of Norwalk, CT, serving 3 day sentence in D.C. prison for carrying banner "Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed." July 6-8, 1917. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In June 1917, members of the ongoing picket began to get arrested. By October, police issued an ultimatum: if the picket continued, protesters could face sentences of up to six months in prison. Many of the arrested protesters were charged with “obstructing traffic” or given fines.

Hunger strikes emerged in the jails and workhouses where protesters were held, leading to force-feeding and other violent practices carried out by prison staff. In response to this, leader Alice Paul marched from the National Woman’s Party headquarters to the White House with a banner reading: “The time has come to conquer or submit for there is but one choice - we have made it” - the same slogan President Wilson used on posters encouraging Americans to buy war bonds.

The day after the police announce that future pickets would be given limit of 6 mos. in prison, Alice Paul led picket line with banner reading "The time has come to conquer or submit for there is but one choice - we have made it." October 20, 1917, Harris & Ewing, Washington, D.C. (Photographer). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Ten months into the ongoing picketing efforts, on November 13, 1917, 33 women were arrested around the White House. By the next day, they arrived at the Occoquan Workhouse, where, demanding to be recognized as political prisoners, they refused to put on prison uniforms or participate in the mandated work shifts.

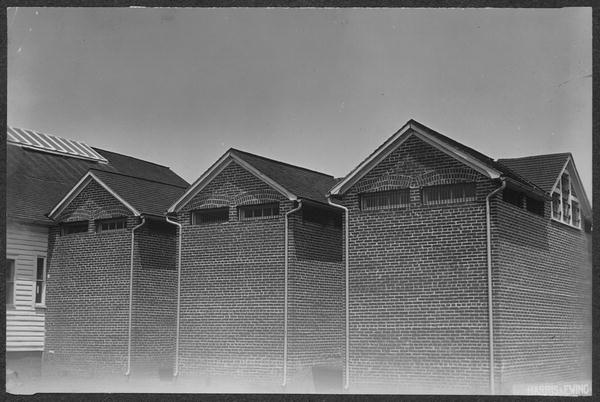

Cell blocks at Occoquan [Workhouse], ca. 1917, Harris & Ewing, Washington, D.C. (Photographer). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The prison guards responded with violence. On orders from Occoquan Superintendent W.H. Whittaker, guards physically assaulted the women and threw them into dark and filthy cells.

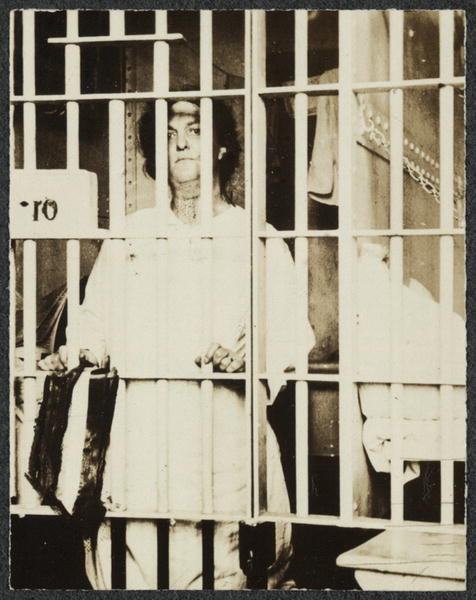

One suffragist, Dora Lewis, was violently thrown down, hitting her head on an iron bed. Alice Cosu, who witnessed this, suffered a heart attack and did not receive medical treatment until the next day. Organizer Lucy Burns was chained with her hands over her head to the bars in her cell and forced to stand for the entirety of the night. Fellow protester Julia Emory assumed the same position for the night in solidarity.

One of the protesters, Doris Stevens, wrote an account of the “Night of Terror” entitled “Jailed for Freedom,” which chronicled the events of their imprisonment. She included excerpts of Lucy Burn’s accounts, which were recorded clandestinely during her imprisonment on scraps of paper and smuggled out of the workhouse.

Miss [Lucy] Burns in Occoquan Workhouse, November 1917, Harris & Ewing, Washington, D.C. (Photographer). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

Burns writes: “(Whittaker) refused to hear our demand for political rights. Seized by guards from behind, flung off my feet, and shot out of the room. All of us were seized by men guards and dragged to cells in men’s part.”

During their time in Occoquan, many arrestees resorted to hunger strikes. In response to this, the guards force-fed the women raw eggs and milk, causing them to become ill. At one point, marines from the nearby Quantico Station were brought in to support the Occoquan guards. By the time the women were released, many were too weak to walk on their own.

Kate Heffelfinger after her release from Occoquan Prison, ca. 1917. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The imprisoned suffragists were returned to D.C. after a November 23 ruling determined that, since they were arrested in D.C., it was illegal to incarcerate them in Virginia. By November 28, they were out on bail, and by March of the following year, all of their arrests had been declared unconstitutional.

In early January 1918, President Wilson expressed his support for the voting rights amendment, which passed in the House but failed in Senate. It would take until 1920 before the amendment was formally incorporated into the U.S. Constitution. The “Night of Terror” remains a pivotal point in the struggle for suffrage, a true show of the solidarity of the protesters and the lengths to which they would go for their cause – and the lengths their opposition would go to hamper their efforts.

Research sources used in this piece:

- The Night of Terror: When Suffragists Were Imprisoned and Tortured in 1917 - History.com

- Wilson and Women's Suffrage - PBS American Experience

- Suffragist History - Turning Point Suffragist Memorial

- Women of Protest: Photographs from the Records of the National Woman's Party - Library of Congress

- History of the Workhouse - Workhouse Art Center

- "In 1917, the ‘Night of Terror’ at a Virginia prison changed history. Now it’s a site of beauty" - Los Angeles Times

- "‘Night of terror’: The suffragists who were beaten and tortured for seeking the vote" - Retopolis, Washington Post

Read about Gertrude Crocker, Arlington's own Silent Sentinel suffragette, also jailed multiple time in 1917.

Learn more in these books available at the Library:

- "The long loneliness: the autobiography of Dorothy Day," by Dorothy Day

- "Mr. President, how long must we wait?: Alice Paul, Woodrow Wilson, and the fight for the right to vote," by Tina Cassidy

- "Votes for women!: American suffragists and the battle for the ballot," by Winifred Conkling

2020 marks the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States.

![Alice Paul banner Photograph of Alice Paul emerging from National Woman's Party headquarters holding banner, followed by Dora Lewis (with no banner). Unidentified women stand with a banner in doorway of building. Banner Paul carries reads: "The Time Has Come to Conquer or Submit, For Us There Is But One Choice. [I] Have Made It. President Wilson." Paul is leading picket line from headquarters to the White House.](https://library.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Alice-Paul-banner.jpg)