May 4, 1912

Celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with stories about the people and events that led to the passage of women’s suffrage in the United States.

Over 100 years ago this week a 16-year-old suffragist named Mabel Ping-Hua Lee made history when she lead one of the major women’s suffrage marches in New York City.

Dr. Mabel Lee, date unknown. Photo from the George Grantham Bain Collection, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Lee was born near Hong Kong in 1896 and moved to the United States in 1905 to join her father, who was serving as a missionary. Lee was granted a visa as part of an academic scholarship and attended the Erasmus Hall Academy in New York City, one of the oldest schools in the nation.

Throughout her teens, Lee grew increasingly involved in New York’s suffrage movement. On May 4, 1912, Lee rode on horseback at the head of a parade to advocate for women’s voting rights, along with suffragists Annie Rensselaer Tinker, Anna Howard Shaw (carrying a banner from the National American Woman Suffrage Association), and members of the Women’s Political Union. Ten thousand people attended this gathering, which started in Greenwich Village.

She later spearheaded another major march in 1917, leading Chinese-American women in a pro-suffrage parade down Fifth Avenue along with the Women’s Political Equality League.

“Youngest parader in New York City suffragist parade.” Participants in the May 4, 1912, women’s march in New York City that Mabel Lee helped to lead. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Lee later attended Barnard College, an all women’s school founded because the nearby Columbia University refused to admit women at the time. There, Lee was part of the Chinese Students’ Association and wrote feminist essays – among them “The Meaning of Women’s Suffrage,” written in 1914. In this piece, Lee argued that suffrage for women was essential to a successful democracy.

She also continued her advocacy work as a speaker, and in 1915 delivered a speech on behalf of the Women’s Political Union, which was covered by the New York Times. Entitled “The Submerged Half,” it urged members of the Chinese-American community to promote girls’ education and women’s participation in civic life.

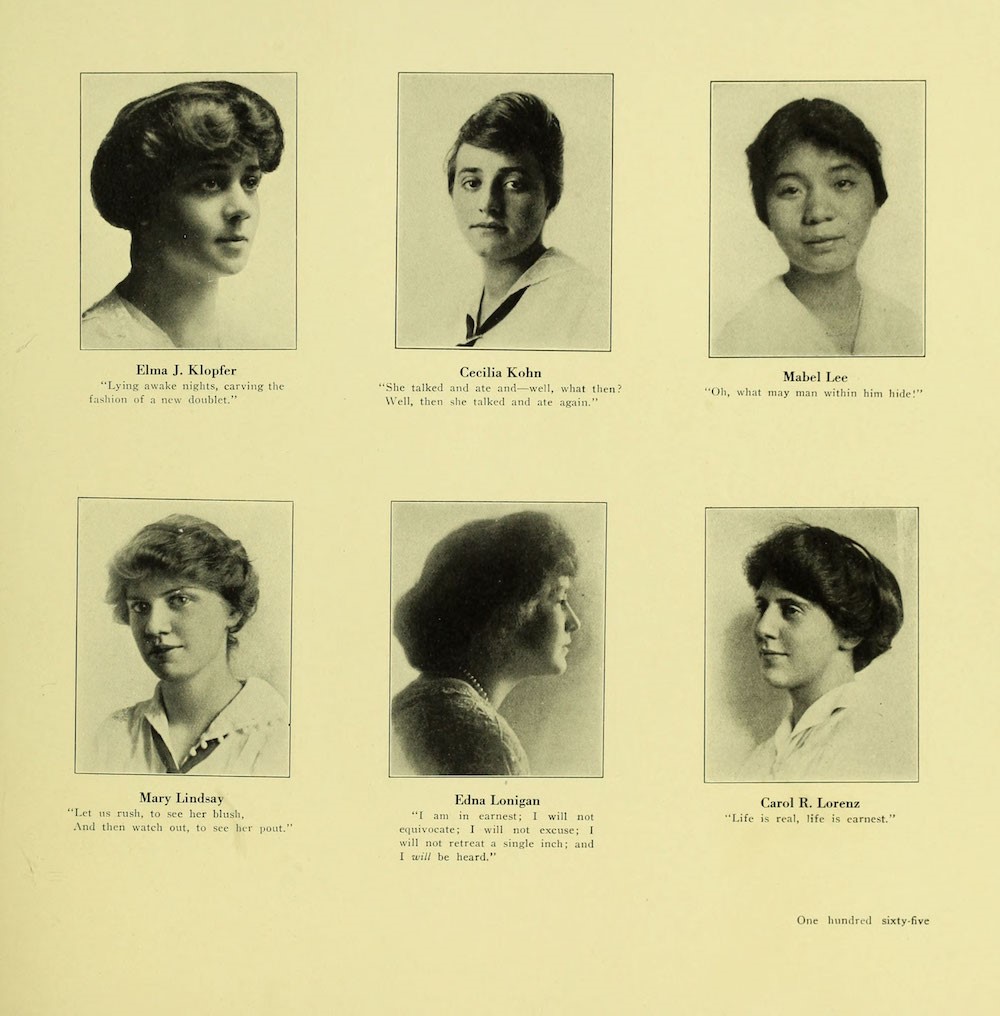

Mabel Lee in her Barnard College yearbook. Image courtesy of Barnard College.

Though women were granted the right to vote in New York in 1917, and nationally in 1920, Lee’s fight for universal suffrage would continue onward. The reality was that not all women benefitted from these laws: under the Chinese Exclusion Act, Chinese women were not allowed to vote. Under the law, which also limited Chinese immigration, Chinese immigrants were not allowed to become citizens, and Chinese women like Lee would not be able to vote until the law was removed in 1943 and they could become citizens. Despite these barriers, Lee and fellow suffragists continued to advocate for women’s rights.

She also went on to receive a Ph.D. in economics at the previously all-male Columbia University, the first Chinese woman to do so. Later in life, Dr. Lee also served as director of the First Chinese Baptist Church in New York City.

Dr. Mabel Lee died in 1966. In 2018, U.S. Congress approved legislation to rename the United States Post Office at 6 Doyers Street in China Town, New York City, in her honor.

Lee was featured in an April 13, 1912, New York Tribune article prior to her participation in the women’s march in New York City on May 4. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Read More:

NY Times Article from May 5, 1912, about the suffrage parade.

2020 marked the centennial of women’s suffrage in the United States.

Thank you for sharing the story of Dr. Mabel Lee. I had never heard of her. There are so many unsung heroines of the suffrage struggle. And to think Dr. Lee worked for the vote when Chinese women could not benefit until restrictions were lifted in 1943.