May 10, 1866: 11th National Woman’s Right Convention

Celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with stories about the people and events that led to the passage of women’s suffrage in the United States.

In 1866, the women’s suffrage movement experienced a significant change in its organization as the various groups leading the struggle toward women’s suffrage split over certain issues.

Key among them was support for the 15th Amendment, (passed in 1869), which states that "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

American Equal Rights Association

One of the major groups leading the suffrage movement at this point was the American Equal Rights Association (AERA). The organization was founded on May 10, 1866, at the eleventh National Woman’s Right Convention by suffrage leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony. The group outlined its goal to “secure Equal Rights to all Americans citizens, especially the right of suffrage, irrespective of race, color, or sex.”

The AERA featured a diverse group of members, many prominent figures in the suffrage and abolition movements. Among those who played significant roles in the group were Lucretia Mott, Lucy Stone, Frederick Douglass, and Henry Blackwell. A number of African-American women also held leadership roles, including Harriet Purvis, Sarah Remond, and Sojourner Truth.

Elizabeth Cady Stanton (left) and Susan B. Anthony (right). Stanton and Anthony broke off to form the National Woman Suffrage Association in 1869 after disagreement over the 15th Amendment, which they both opposed. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Advocacy for All

The American Equal Rights Association was initially focused on advocating and campaigning for the rights of both women and African Americans in the United States, and on gaining suffrage for both.

At the first anniversary meeting of the group, on May 9 and 10 in 1867, the group’s leadership wrote:

“Let the gathering, then, at this anniversary be, in numbers and character, worthy, in some degree, the demands of the hour. The black man, even the black soldier, is yet but half emancipated, nor will he be, until full suffrage and citizenship, are secured to him in the Federal Constitution. Still more deplorable is the condition of the black woman; and legally, that of the white woman is no better!

Shall the sun of the nineteenth century go down on wrongs like these, in this nation, consecrated in its infancy to justice and freedom? Rather let out meeting be pledge as well as prophecy to the world of mankind, that the redemption of at least one great nation is near at hand.”

Divisions in the AERA

This approach was short-lived, however, as prejudices were increasingly exposed in the group. This was particularly clear in New York and Kansas, two states with notable and controversial suffrage campaigns led by the AERA.

The New York campaign focused on entering women’s suffrage into the state’s constitutional revisions, as well as fighting discrimination against Black voters. Horace Greeley, a notable newspaper editor, and abolitionist, was chair of this campaign’s suffrage committee, and later came into disagreement with Stanton and Anthony. Greeley wanted to focus solely on Black male suffrage, while Stanton and Anthony wanted the focus on white women's suffrage.

The Kansas campaign was even more pivotal to the split, as the state was about to vote on both suffrage for white women and suffrage for African American men. Stanton and Anthony decided to back George Train, who used racist vitriol to further his campaign against granting African American men suffrage. Anthony’s writing also became more anti-Black during this time. Other members of the AERA stood up against this approach, notably Lucy Stone, but ultimately neither suffrage bill passed in Kansas.

In 1869, a final blow was dealt to the existing structure of the women’s movement. Two days prior at the AERA annual meeting, acrimonious debates had marked the group’s discussions. Frederick Douglass notably called out Stanton for denigrating Black male voters in her work in Kansas.

Two days later, on May 15, 1869, the AERA disbanded permanently. On that same day, Stanton and Anthony broke off to form the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA).

The executive committee of the National Woman’s Suffrage Association. Image courtesy of Spartacus Educational.

National Woman Suffrage Association / American Woman Suffrage Association

Headquartered in New York City, the aim of National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) was to promote suffrage for white women and to oppose the 15th Amendment.

Later that year, another group emerged: led by Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Brown Blackwell, as well as Julia Ward Howe, the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) supported the 15th Amendment along with women’s suffrage.

The split between these two groups lasted nearly two decades. However, in 1890, Lucy Stone’s daughter, Alice Stone Blackwell, successfully led a merger, leading to the creation of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). (Among the founding members was Washington DC activist Mary Church Terrell.)

This was the first time in decades the suffrage movement had been united under one banner, but racism within the movement persisted. Though the group was not segregated nationally, local chapters could and did exclude African American women. The struggles and shifts in these groups demonstrate the deeply ingrained prejudices that have accompanied the American suffrage movement for decades.

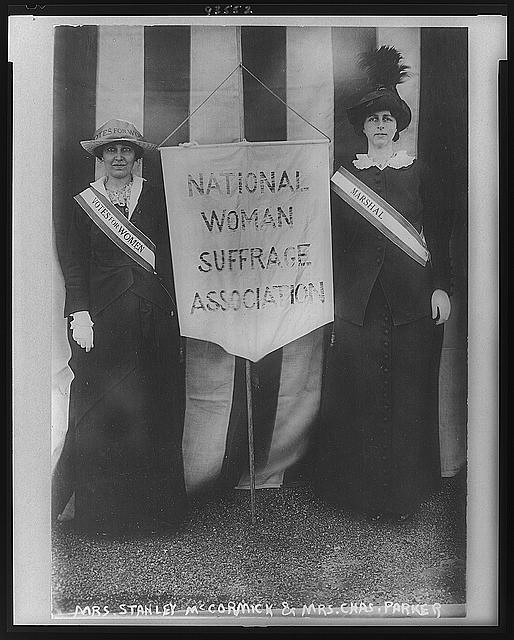

“Suffragists Mrs. Stanley McCormick and Mrs. Charles Parker, April 22, 1913.” Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“Horse drawn float declares National American Woman Suffrage Association’s support for Bristow-Mondell amendment.” Circa 1914. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

2020 marked the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment.