May 20, 1961: Nannie Helen Burroughs Passes Away

Celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with stories about the people and events that led to the passage of women’s suffrage in the United States.

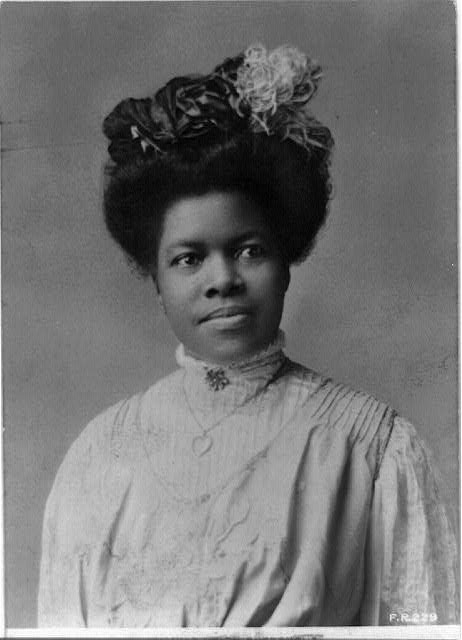

Nannie Helen Burroughs, who was a leading educator, feminist and suffragist in the Washington, D.C., area throughout the early 20th century, founded a school for girls and women and was an active member in her community.

Portrait of Nannie Helen Burroughs (left) and unidentified companion, ca. 1900. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Early Life

Burroughs was born on May 2, 1879, in rural Orange, Virginia. Both of her parents were formerly enslaved, and her father passed away when Burroughs was a young girl. She and her mother subsequently moved to Washington, D.C., where Burroughs spent the majority of her childhood.

She was an exemplary student and graduated with honors from the M Street High School, now the Paul Laurence Dunbar High School. Though she excelled academically, she was denied a teaching job in the Washington, D.C., public school system – however, this setback would not hinder her goal to further the education of those in need.

Nannie Helen Burroughs (center) and others at the National Training School in Washington, D.C., taken around 1909. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Training School

Burroughs then decided to establish her own school to educate and train African American women who could not pursue a traditional educational path. Burroughs brought her proposal to the National Baptist Convention, and the organization decided to support her idea. The group bought six acres of land in the Lincoln Heights area of Northwest Washington, D.C., but this was only the beginning of her journey to open the school. Not wanting to rely on wealthy white donors, Burroughs gained the support of small donations from African American women and children to raise the funds to open the school. Once the fiscal matters were in order, Burroughs was able to open the National Training School for Women and Girls in 1909.

Originally operating out of a small farmhouse on the property, the school was popular and well-attended through the first half of the 20th century. The curriculum at the school was rigorous, including courses both vocational and academic, such as dressmaking, power machine operation, music, and physical education. Students could also participate in activities such as the school newspaper. Most of the students came from working-class backgrounds and hailed both from the Washington, D.C., area and other countries around the world.

Early supporters of the school included Black history scholar Dr. Carter G. Woodson and president of the National Association of Colored Women, Mary McCleod Bethune, who also spoke at the dedication ceremony. Burroughs outlined her goals for the school as training women for jobs both in and outside of the traditional female job sphere, and aiming for each student to become “the fiber of a sturdy moral, industrious and intellectual woman.” In 1928, the school saw an expansion, and a larger building – called Trades Hall – was constructed, with 12 classrooms, three offices, an assembly hall, and a print shop.

Student basketball players at the National Training School for Women and Girls, between 1900 and 1920. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Woman’s Convention of the National Baptist Convention

At the same time as Burroughs lead her school and students, she was also an activist and advocate. Notably, she was involved in supporting greater civil rights and suffrage for African Americans and women. She wrote and spoke extensively on these topics, highlighting the need for African American and white women to work together to achieve the right to vote for all. She also emphasized that suffrage for African American women was key in protecting them in a persistently prejudiced and discriminatory society.

Starting early in her career, she was active in the Woman’s Convention of the National Baptist Convention, many of whose members were fellow suffragists and who discussed suffrage topics at their meetings. In 1900 she delivered a speech at the group’s annual meeting entitled “How Sisters Are Hindered from Helping,” and at the 1905 First Baptist World Alliance meeting in London, gave a speech called “Women’s Part in the World’s Work.” Burroughs also served as the corresponding secretary of the Woman’s Convention for 48 years and helped the organization grow its membership to 1.5 million by 1907.

“Nine African-American women posed, standing, full length, with Nannie Burroughs holding banner reading, Banner State Woman's National Baptist Convention.” Published between 1905 and 1915. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Legacy

Throughout her life she also became part of the vibrant community of African American women suffragists, advocating for the cause alongside Coralie Franklin Cook, Anna Julia Cooper, Angelina Weld Grimké, Lucy Diggs Slowe, and Mary Church Terrell. African American women’s clubs were a strong network in Washington, D.C., and Burroughs was also active in these groups, including the National Association of Colored Women, the National Association of Wage Earners, and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.

Burroughs served as president of her school until her death on May 20, 1961, and three years later, the school changed its name to the Nannie Helen Burroughs School in her honor. Trades Hall now houses the Progressive National Baptist Convention and is a National Historic Landmark.

Nannie Helen Burroughs photographed between 1900 and 1920. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

2020 marked the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment.