Virginia has a long history of horse and car racing, and Arlington County has had a role in both of these historically popular pastimes.

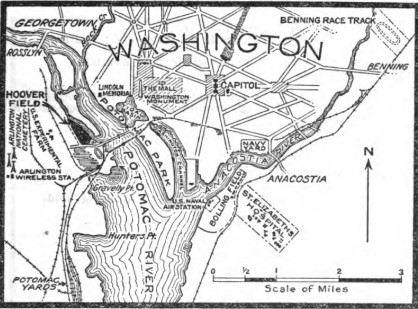

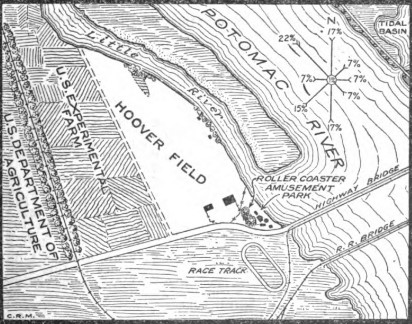

Beginning in the 1890s, Arlington (then known as Alexandria County) was home to a half-mile-long racetrack that drew thrill-seekers and daredevils from the County and beyond. The track, located on the grounds of what would become the Washington Airport next to the Hoover Airport, was on the land south of 14th Street bridge now occupied by the Pentagon.

Racing venues like Alexander Island in Arlington, and the St. Asaph Racetrack in Alexandria also became the focus of nationwide anti-gambling measures around the turn of the century.

A Racetrack for Arlington’s “Miniature Monte Carlo”

Arlington’s racetrack has its origins in the controversial history of the now extinct Jackson City neighborhood, and its then twin, Rosslyn. In the late 19th century, the two areas were considered hubs of criminality, associated with betting, gambling, and other unsavory activities.

Jackson City was even referred to as a “Miniature Monte Carlo.” Following the post-Civil War ban on gambling in Washington, D.C., the neighborhoods drew customers across the Potomac to Rosslyn, conveniently located by the Aqueduct Bridge, and to Jackson City at the Long Bridge.

An article from the Washington, D.C., Evening Star on January 30, 1892, alludes to the controversial nature of the Jackson City area in Arlington. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

In the 1890s, Virginia lawmakers attempted to control the gambling that had overtaken the state, but corrupt legislators slipped in a loophole to allow an exemption for driving clubs, agricultural organizations, and grange organizations. Thanks to this provision, the Jones family in Arlington was able to secure a charter from the Grange Camp Association of Virginia and began investing in a racetrack in Jackson City.

Over the years, the racetrack would sometimes be referred to as the “Alexander Island” racetrack, referring to the also-controversial piece of land it sat on, which was considered Virginia at low tide and Washington, D.C., at high tide.

When a judge ruled the racetrack could stand, this set the precedent for the area formerly being considered part of Virginia – as horse betting was illegal in the District. This decision was later reversed in the 1930s, but Alexander Island ultimately came under the Pentagon’s jurisdiction a decade later and is now the present-day site of the Connector Parking Lot.

The City of Alexandria’s Racetrack Rises

Around the same time the Arlington racetrack got its start, investors in the city of Alexandria were also capitalizing on the loose gambling laws. A Gentlemen’s Driving Club was chartered in 1888, and by 1894 this would materialize into the St. Asaph Racetrack – the more notorious track in the Northern Virginia region.

This track was backed by the Hill family and other numerous high-profile investors, among them Virginia Senator George Mushback, who had helped pass legislation allowing for gambling to continue.

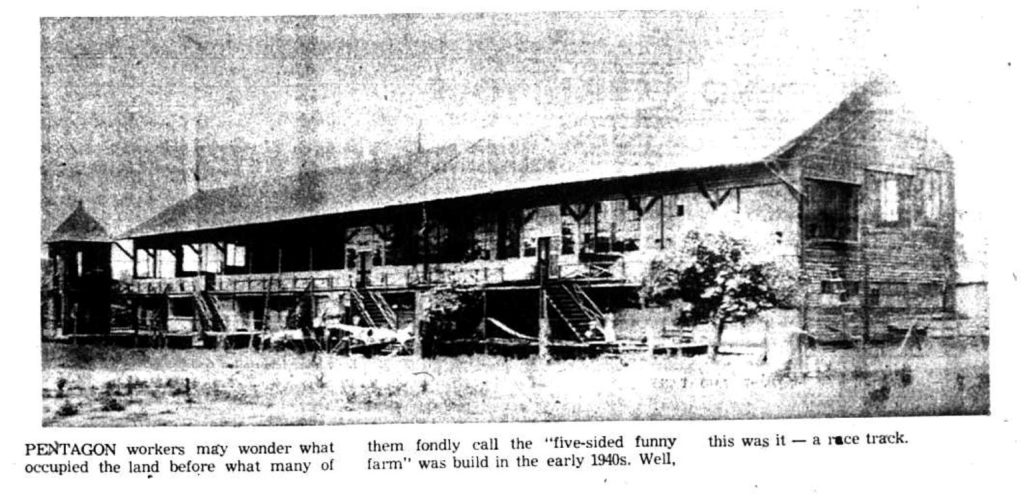

Photo from the Northern Virginia Sun, October 8, 1970, for an article titled “Arlington-- Yesterday and Today.” Though the caption and title suggest this was the Arlington racetrack, this photo is of the St. Asaph grandstand.

Located in the Del Rey neighborhood, the St. Asaph racetrack was extremely popular, drawing in thousands of dollars on its racing days. The operation made an estimated $150,000 per year – bolstered by its poolroom, where gamblers could stay connected and bet on other races via the establishment’s telegraph wires. The track was ¾ miles long and was frequently noted for the beauty of the landscape and architecture.

By 1895, the competing Arlington and city of Alexandria tracks and their investors had reached an agreement to race on alternate days, keeping both in business. In 1897, horse racing was outlawed outright by the state, though betting for out-of-state races at St. Asaph continued with the racetrack’s extensive telegraph setup. In 1898, during the Spanish-American War, St. Asaph’s was also used by the U.S. Army as a mobilization camp.

Maps from July 6, 1927, Airway Bulletin (No. 124) show Arlington’s racetrack adjacent to Hoover Field. Image courtesy of the University of California.

Drama, Debauchery, and Depositions

The scale of the St. Asaph’s track eventually made it a target for Crandal Mackey, who after being elected the commonwealth’s attorney in 1903, set his sights on eliminating crime in the region. Mackey had become a prominent figure in both Rosslyn and Jackson City, shutting down the area’s illegal bars, bordellos, and casinos over his tenure, and the racetrack was next on his list.

After Mushback’s death, Mackey swooped in to take down the racetrack and its not-so-savory reputation. In May of 1904, he staged a dramatic raid on the track, backed by a posse with sledgehammers and axes who destroyed slot machines and other equipment.

However, the track soon resumed business as usual. Mackey would eventually obtain 19 warrants against the track’s owners, igniting an extended courtroom battle against some of the region’s richest and most prominent figures. Mackey was ultimately successful in 1905 when the St. Asaph racetrack shut down for good.

“Flood with racetrack in the background,” Image of the abandoned St. Asaph Racetrack, 1924, with the Arlington radio towers in the background. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Memories of the Arlington Racetrack

It’s unclear why the Jackson City racetrack eluded Mackey’s “shotgun justice,” but it managed to disassociate itself from the historical notoriety of its Alexandria counterpart.

In the early 1900s, the Arlington racetrack remained a place for spectators to take in the thrills of the burgeoning sport of car racing. It was also near another popular spot for Arlingtonians to pass the time, the Arlington Beach, which featured a dance hall and amusement park rides.

Want to learn more about early 20th Arlington? Check out “Shotgun Justice: One Prosecutor’s Crusade Against Crime and Corruption in Alexandria & Arlington,” available at the Library.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Charlie Clark Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields