1908

Arlington is the home to the country’s first military test flights, which lead directly to the adoption of aircraft for military use. Orville Wright came to Arlington in 1908 to demonstrate his new flying machine for the U.S. Government and U.S. Army.

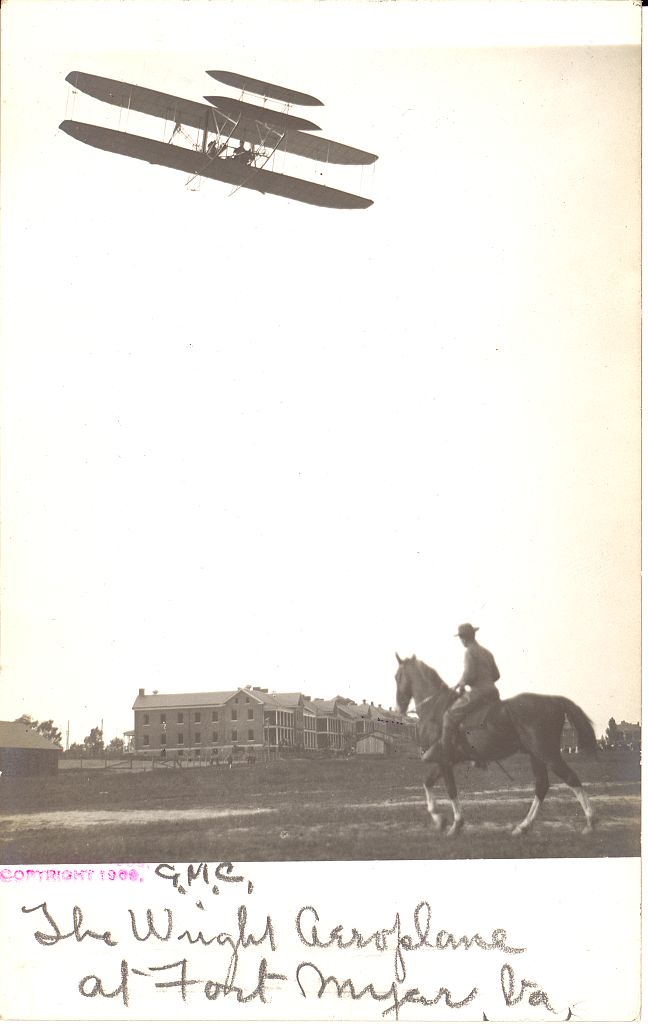

Wright and his assistants arrived in late August 1908, bringing the aircraft from Ohio. Over the course of several days, Wright would perform small flight tests at Ft. Myer in the hopes of selling the machine to the Army. Wright began making small test runs across the parade field on September 3, and by September 9, the flights began to last over an hour, with Orville flying 40mph 120 feet in the air, in front of huge crowds that gathered to watch as he broke multiple existing flight records.

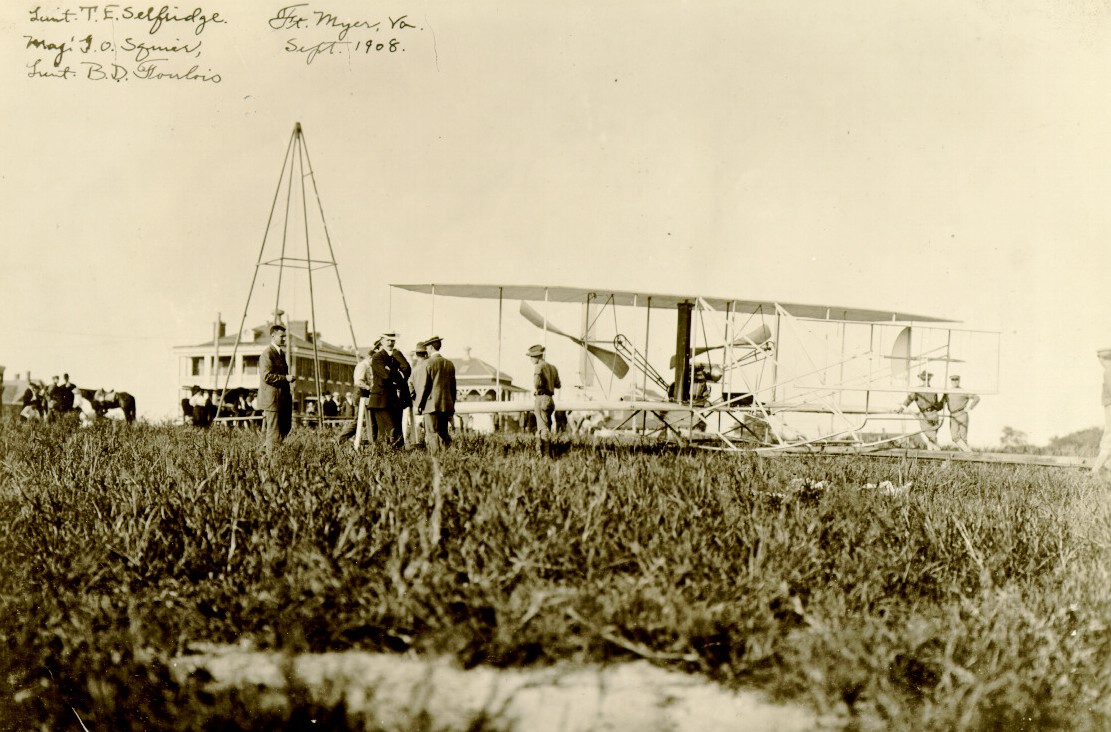

Orville Wright, Lt. Thomas Selfridge, Major Squire, and Lt. Benjamin D. Foulois with flyer at Ft. Myer, September 1908, Photo Courtesy of Wright Brothers History

One of those watching was Gutzon Borglum, an American sculptor best known for working on Mount Rushmore. In an attempt to describe the plane, he said,

“Within stood the most unlikely, spider-like frame, with twin cotton covered, horizontal frames, one above the other, about six feet apart. There is nothing about the contraption that would suggest to the lay mind its possible use, should he find it unattended in a field; nothing that would suggest to him what it might do or that it was built for anything in particular."

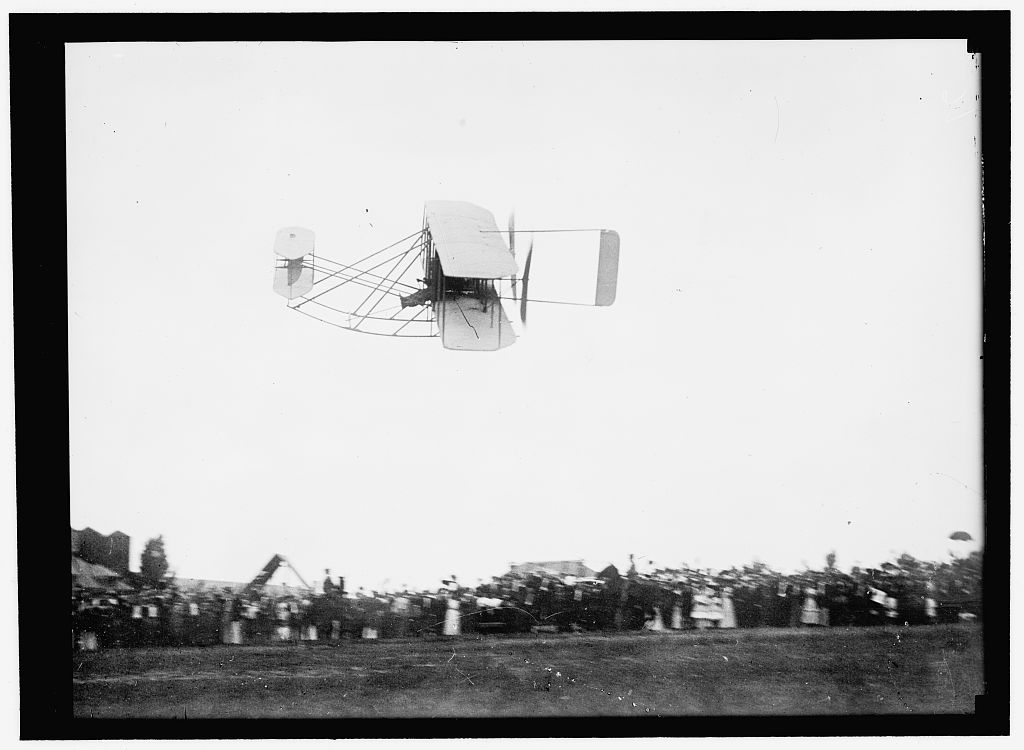

Orville Wright and Lieutenant Lahm flying at Fort Myer, July 27, 1909, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

After witnessing the flight, he said,

“There is no action of the ‘wings’ so you do not think of birds... It is so simple, it annoys one. It is inconceivable, yet having seen it, it now seems the most natural thing in the air. One is amazed humankind has not built it before…As soon as the motor started, the plane gave a slight jump forward. The wind from the propellers drove the hats from the spectators' head…The crowd stood open mouthed, with murmurs of wonder and an occasional toot from an automobile horn; then as he passed over us everybody let go in an uproar of shouting and handclapping. The miracle had happened! Nothing can take this step made into space from man."

Although the tests started well, they would end in disaster. On September 17, Wright took Lt. Thomas Selfridge, an aspiring Army aviation expert, on a test flight. Shortly after takeoff, one of the propellers split, sending the aircraft into the ground. Wright would suffer serious but nonlife threatening injuries, and Lt. Selfridge would later die on the operating table, making him the first victim of an accident in a powered aircraft. Because of the failure, the U.S. Army delayed further tests of this version of the aircraft until the problems could be fixed.

Bystanders work to free Lt. Selfridge, 1908, Ft. Myer, Photo Courtesy of Arlington Cemetery

Determined not to let the fatal crash hurt their reputation, the Wrights resumed test flights in early July of the following year. Because of the highly publicized crash the year prior, thousands of people came to observe the tests. This included President Taft, members of Congress, Senators, high ranking Army officials, and other influential people such as Evelyn Roosevelt.

Senators Kean, Lodge, and Bacon with wives at Ft. Myer test flights, July 1909, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

Photographers at military flight trials, Ft. Myer, July 1909, Photo Courtesy of Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

The resumption of tests got off to a rocky start, requiring Wright to briefly return to Ohio to repair a torn wing. By July 12 however, Wright was able to consistently fly hour-long flights over Fort Myer. On the final acceptance test, Wright needed to fly 10 miles - from Fort Myer to Shooters Hill in Alexandria (now the George Washington Masonic Memorial), maintaining at least 40 mph and receiving a bonus of $1,000 for every mph he went faster.

Similar to the previous tests, Orville took passengers on test flights in the Arlington area to demonstrate the aircraft's speed and durability. On one flight, Wright took Major General Benjamin D. Foulois, who described the event 50 years later:

“Orville Wright, in his quiet little voice, asked me if I wouldn’t be the observer on that trip and his navigator. He picked me, I found afterwards, because I was the smallest one of the group - less wind resistance, less gasoline…When I got into the airplane with him, he quietly turned to me and said, ‘If we have any trouble on this trip, I’m going to pick out the thickest clump of trees I can find and land in it’, which sent a little reminder to me that I’d picked out a course with no landing fields on it…”

Washington Post, July 31st, 1909, Access Provided by ProQuest

First Army Aeroplane Flight, Fort Myer, Virginia, July 1909, Video Courtesy of UK National Archives

Although Wright and Foulois had initially overshot Alexandria, they were able to successfully return and land back at Ft. Myer. The test was a resounding success. Wright’s last test run with Foulois passed all of the Army’s requirements, and they purchased the world’s first military aircraft for $30,000.

Lt. Thomas Selfridge would later be honored with the Selfridge Gate in Arlington Cemetery, and the 1909 Wright Military Flyer is on display at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C.

Orville Wright flying, July 1909, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

Orville Wright flying above Ft. Myer, July 1909, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

Help Build Arlington's Community History

The Center for Local History (CLH) collects, preserves, and shares resources that illustrate Arlington County’s history, diversity and communities. Learn how you can play an active role in documenting Arlington's history by donating physical and/or digital materials for the Center for Local History’s permanent collection.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields