Arlington's First Shopping Mall

Before it was known as the Ballston Quarter, Parkington was the largest shopping center on the East Coast and one of the first major shopping malls in the Washington D.C. area.

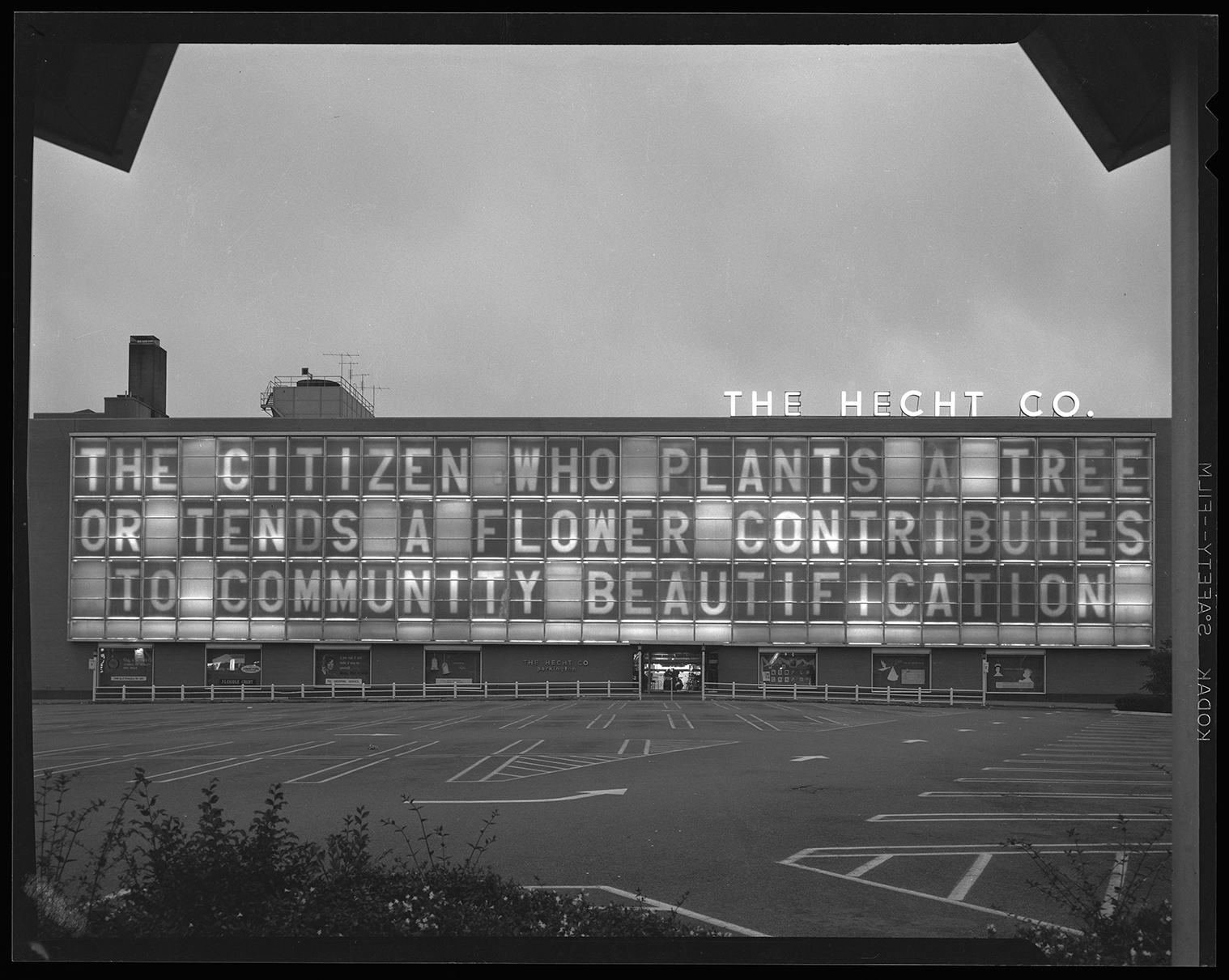

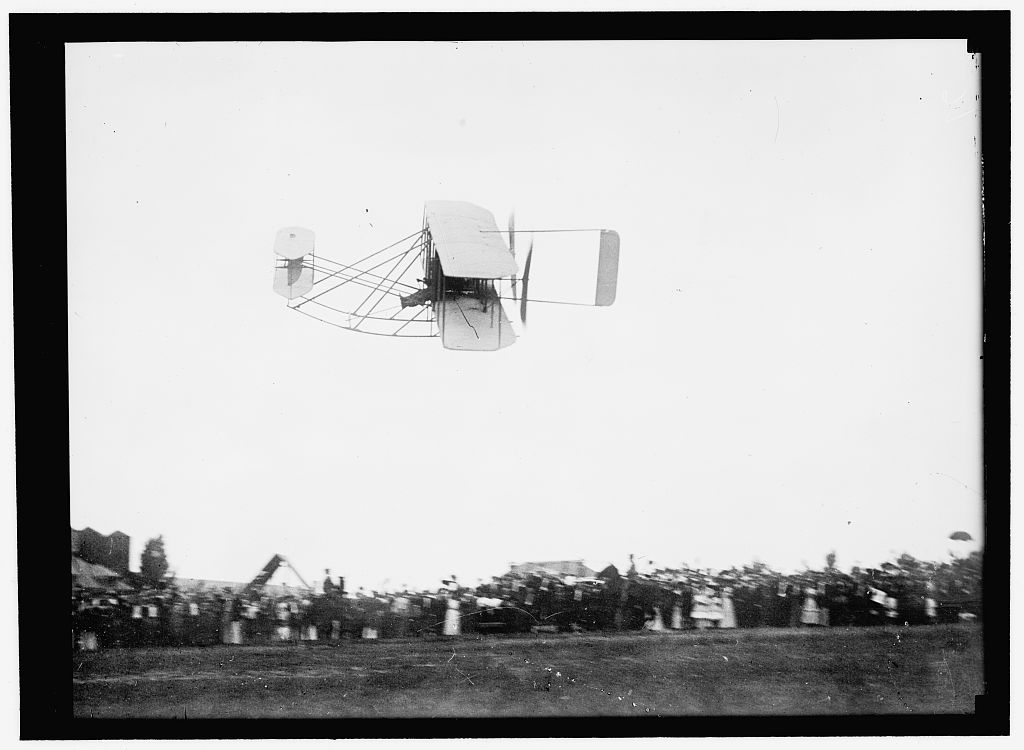

The Hecht Company, c. 1950s, CLH Collections

Publicized as “the area’s most dramatic venture in retail merchandising” when it opened in 1951, Parkington represented the post-war boom in suburban life and centralized, indoor retail shopping.

Located at the historic "Balls Crossroads" intersection of Wilson Boulevard and Glebe Road, Parkington Shopping Center was built on the site of the former Ballston Stadium (video). Used for practice by the Washington Redskins in 1938, the stadium had also been home to many local football games between Arlington neighborhoods under the Arlington County Federation of Boys’ Clubs.

Construction

Financed and constructed by Hecht's Department Store, Parkington was the flagship of Hecht's chain on the East Coast.

During construction, Parkington drew its name from the large, multistory parking garage at the heart of the development. It was described by the Evening Star in 1950 as “the first suburban shopping center with a four tiered parking garage built over a score of retail stores in the middle of the area.”

Officially opened on November 2, 1951, Hecht's was hailed as a "miracle of planning" - a modern and exciting improvement to the shopping experience.

Hecht's had a first aid room staffed by a full time nurse, bridal consultants, maternity shops, and interior decorating services, as well as an auditorium and spaces to hold classes in upholstery.

Birth of the Modern Mall

Many aspects of malls today that are taken for granted were still in the trial phase during the lifetime of Parkington. Newspapers at the time celebrated the “foolproof escalators… one person wide…they’re said to be safer than the broader types” and the way “shoppers may window shop from store to store without fear of being run over by delivery trucks” as well as the novelty of a store that was “fully air conditioned and fireproofed by a sprinkler system.” Features like a public address system throughout the building and background music while shopping were also brand new and helped establish Parkington as a hub of shopping innovation.

Upon opening, the Washington Post described Parkington Shopping Center as,

“A towering green brick building with an all-glass facade, lighted from behind by 180 fluorescent tubes…Hecht customers may drive to the store level in which they wish to shop, park their car, walk a few yards into the store and buy the items they want.”

The concept of the “shopping mall” was so exciting that the BBC, in collaboration with the United States Information Agency, produced a half an hour long program on American shopping malls, with Hecht’s as the focus. Describing Parkington as the blueprint for the modern mall/department store, they said,

“Ten years ago, there was no such shape as this in our American countryside. In recent years, these box-like structures have become part of the semi-rural scene all over America. Today their presence in a village or a suburb is accepted by most Americans without a thought. They’re just part of the changing picture. They are the magnets that attract customers from miles around.”

With the aim of diverting area shoppers to Arlington by the lure of one-stop shopping, the 5 story, 1,146,000 sq. ft. building grew to hold over 30 stores.

Parkington Shopping Center added stores like Walgreens, Giant Foods, McCrorys, Hub Furniture, Stag’s Shops Men’s Clothing, Crawford Clothes, Wilbur Roger’s Women’s Apparel, the Casual Corner, and a Disney themed children’s barber. Restaurants at Parkington included a Polish bakery, South Pacific Polynesian Cuisine and the Virginia Room Restaurant on the basement floor, which held a conveyor belt in order to bring meals and take away dirty dishes.

A Community Fixture

Parkington quickly established itself as an important part of the Arlington community. Hecht’s three story glass wall was used to display messages along the entire block, becoming a local landmark for residents. The “sign” contained eighty-seven 10ft by 14ft canvas panels, which were used to create messages in celebration of the holidays and to support organizations like the Heart Fund and Arlington Beautification Association.

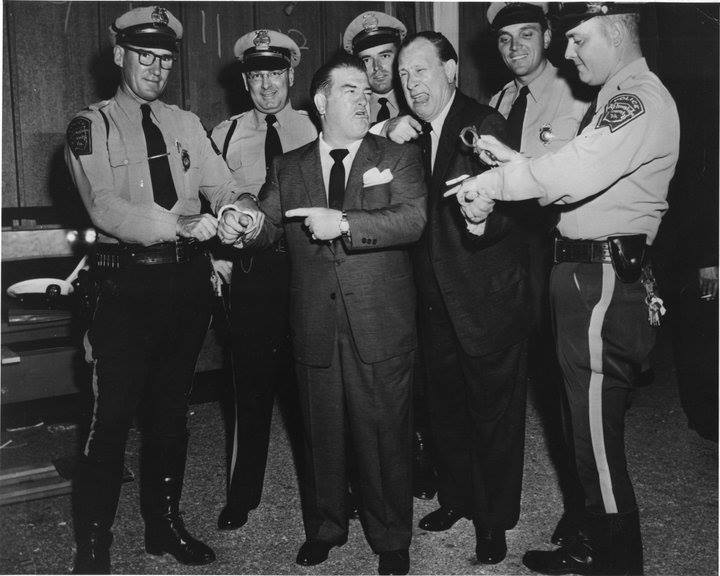

During the 1950s - at its peak in popularity - Parkington drew in local and national celebrities for events. In 1956, after an upgrade to the decorations and murals inside the store, Hecht’s established the “Freedom Fair”, honoring the 15th anniversary of Series E United States Savings Bonds as a way to show off the renovated facilities. Hecht’s brought comedians Abbott and Costello, Charlie Brown cartoonist Charles M. Schulz, artist Norman Rockwell, and actors Virginia Mayo, Michael O’Shea, Buddy Hackett, Jeanne Crain, and “Miss Frances” Horwich to Arlington for shows and events for customers. That same year, Parkington celebrated its 5th birthday with a 12 foot high birthday cake and prizes for local residents.

Parkington's Decline and Closure

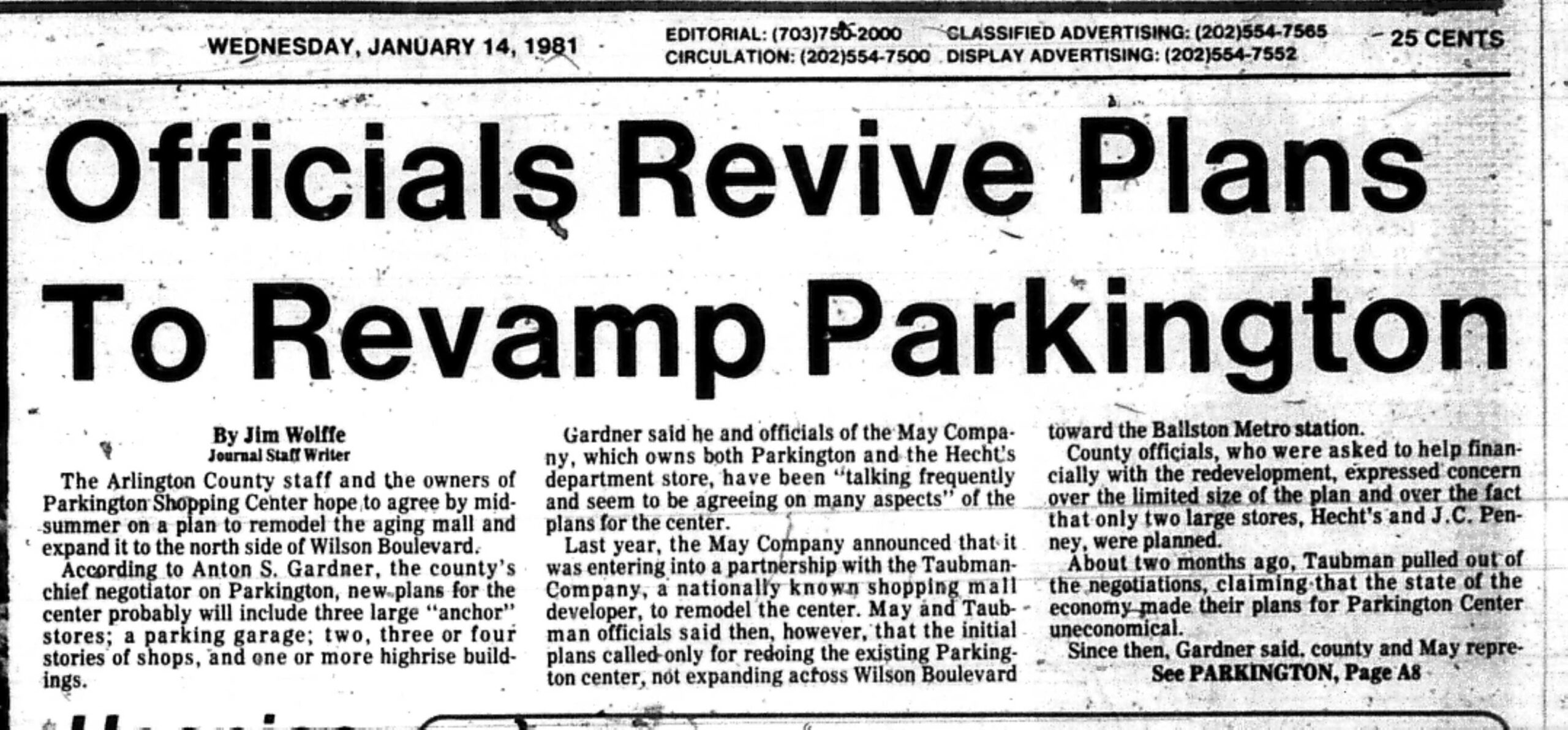

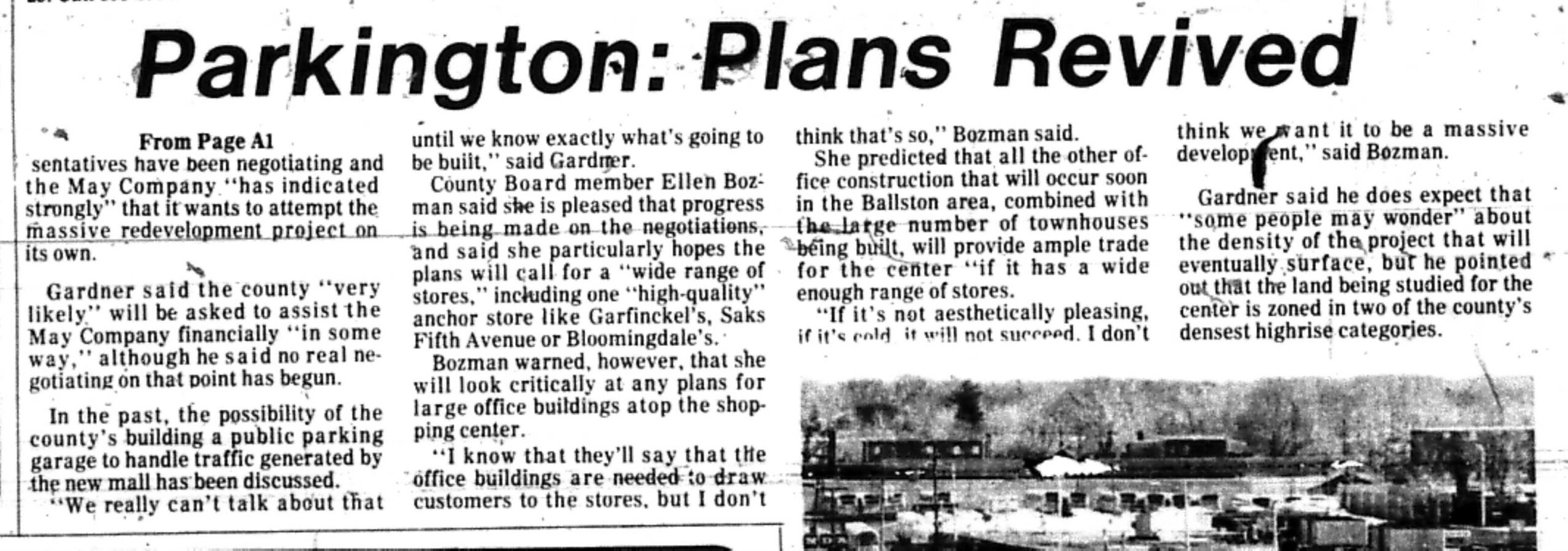

Although Parkington grossed over $223 million in 1959 and expanded with a 12 story office building in 1963, the success would not last long. More department stores and malls opened in the area through the 1960s and 70s, competing with the already aging Parkington complex. By 1979, with the addition of the Ballston Orange Line Metro stop, property value skyrocketed and the 30-year-old facilities were in desperate need of renovation.

Plans were brought forth to completely raze the original structure and rebuild, leaving Hecht’s as the only building standing. After Arlington County approved a $13 million investment in 1982, the $100 million renovation project was officially unveiled, with construction finishing in 1986. A naming contest among Arlington County residents renamed the site from Parkington to Ballston Common Mall for its reopening in October 1986.

The new Ballston Common Mall included 4 stories for retail and nine additional stories were added above the mall to be used as office space. One hundred new businesses, including a J.C. Penneys, were added; the only stores to survive the transition besides Hecht’s were Casual Corner, Waldenbooks, General Nutrition Center, and Dart Drug.

At the end of the 1990s, the Ballston Common Mall was once again in need of changes and by the early 2000s, the parking garage was transformed into the Kettler Capitals Iceplex (the HQ and practice facility for NHL team the Washington Capitals). The Hecht Company was sold to Macy's in 2005 and the Hecht's name was subsequently phased out. By 2016, most of the businesses had been closed in order to redevelop the entire site into the Ballston Quarter.

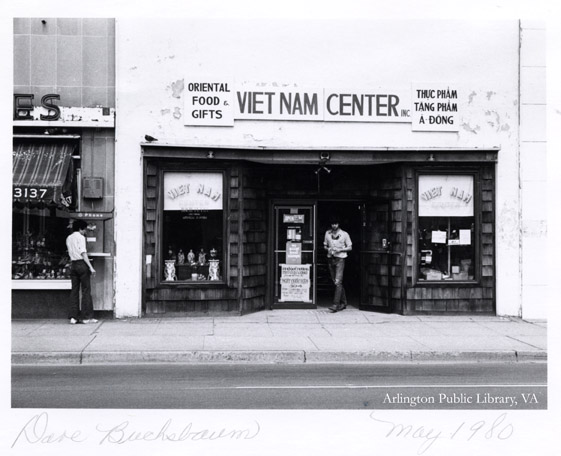

The Francis Copeland Collection

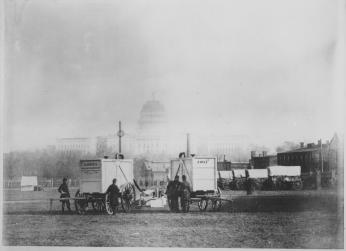

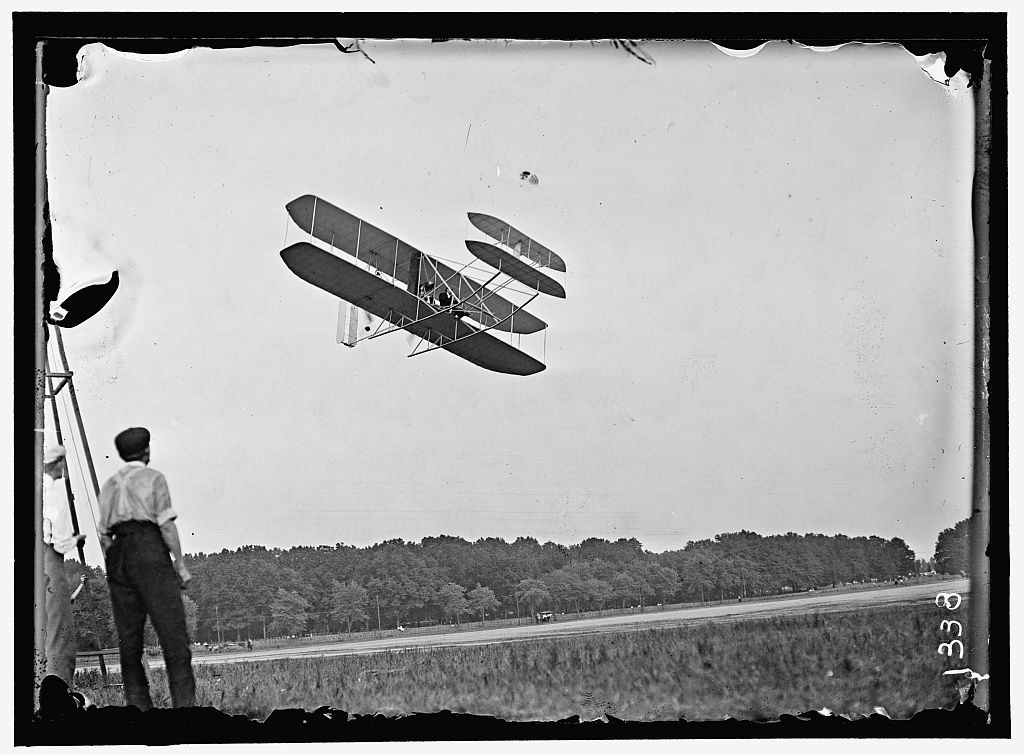

The Francis Copeland Collection at the Center for Local History features over 200 previously unseen images. These photo negatives document the construction of Hecht's and its surrounding Parkington Shopping Center. The photos also offer a glimpse into the 1940s-1950s Ballston neighborhood of Arlington.

Copeland was the Visual Color Lab Manager for Hecht’s Department Store, and worked in their Parkington location during the 1970s. When the store decided to discard a large group of negatives from the 1940s and 1950s, Copeland donated them to the CLH and other archives around the area. To view more photos of Hecht's and Parkington, visit the Francis Copeland Collection.

Help Build Arlington's Community History

The Center for Local History (CLH) collects, preserves, and shares resources that illustrate Arlington County’s history, diversity and communities. Learn how you can play an active role in documenting Arlington's history by donating physical and/or digital materials for the Center for Local History’s permanent collection.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields