Recipes from Over 300 Years

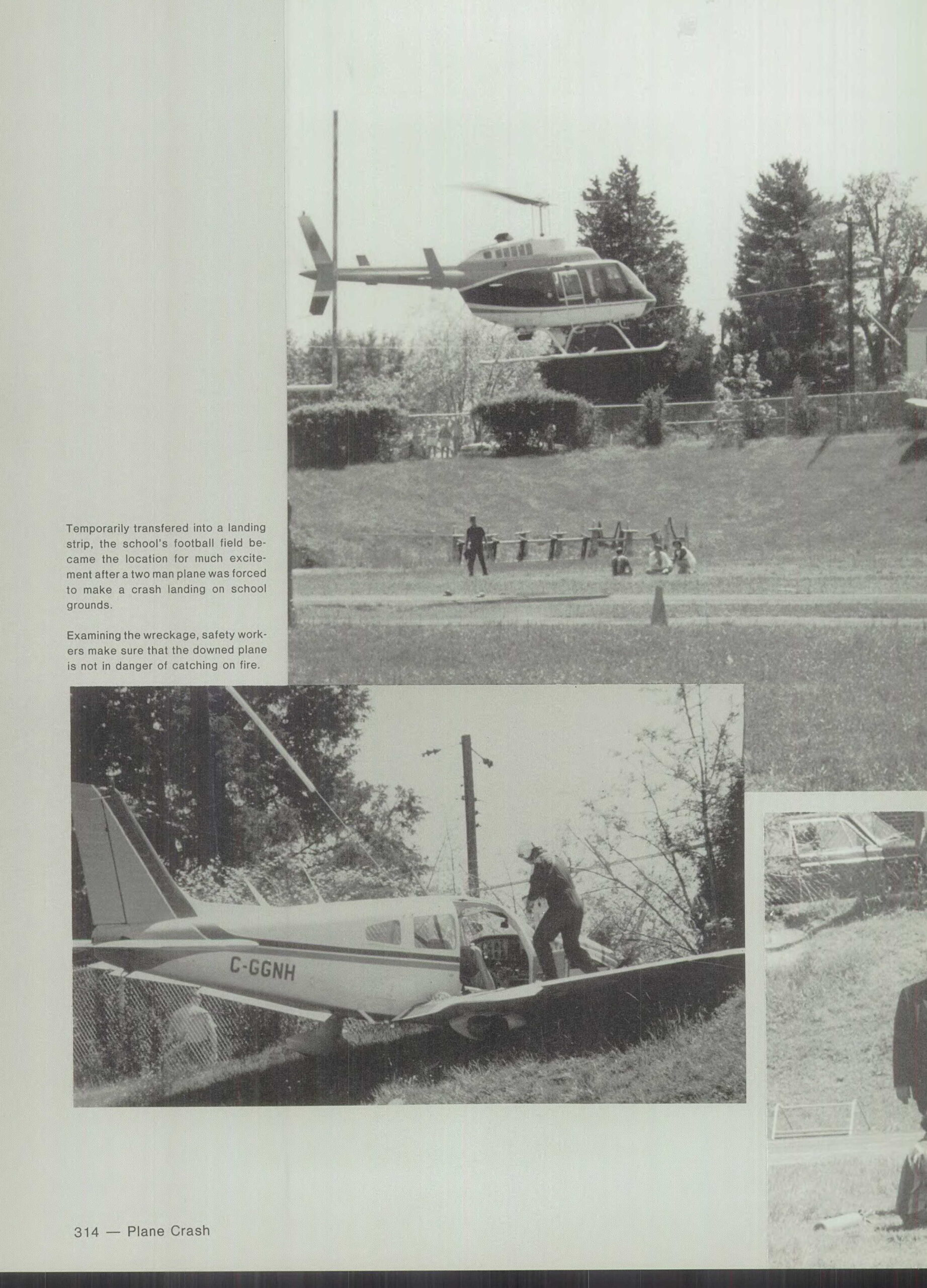

Did you know that the Center for Local History holds dozens of cookbooks that document the history of Virginia cuisine from the 17th century to present day?

This includes recipes copied from the housekeeping books of Woodlawn plantation and George Mason’s Gunston Hall, as well as modern takes on old classics, such as Sally Lunn bread and Brunswick stew.

The most unique cookbooks, however, are the community cookbooks that have been lovingly compiled by various church groups and organizations in Arlington over the years.

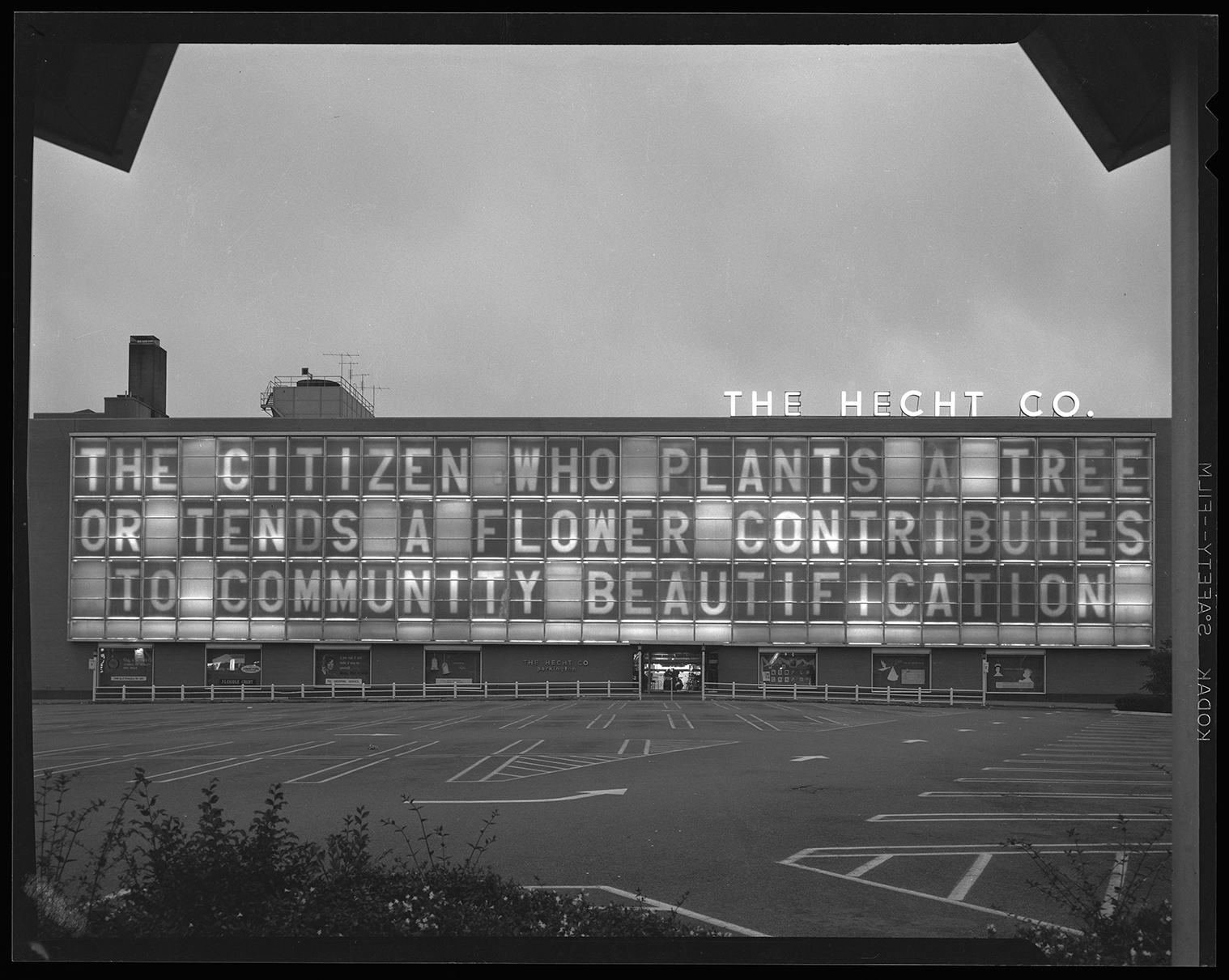

These cookbooks were usually created to raise funds and awareness for different causes in the Arlington community. For instance, the Clarendon United Methodist Church Handbell Choir published Medley of Morsels in December 1986 to raise money to purchase new handbells. In some cases, additional funding was provided by local businesses in exchange for ad space between recipes, providing current readers with a glimpse of bygone eras in Arlington history.

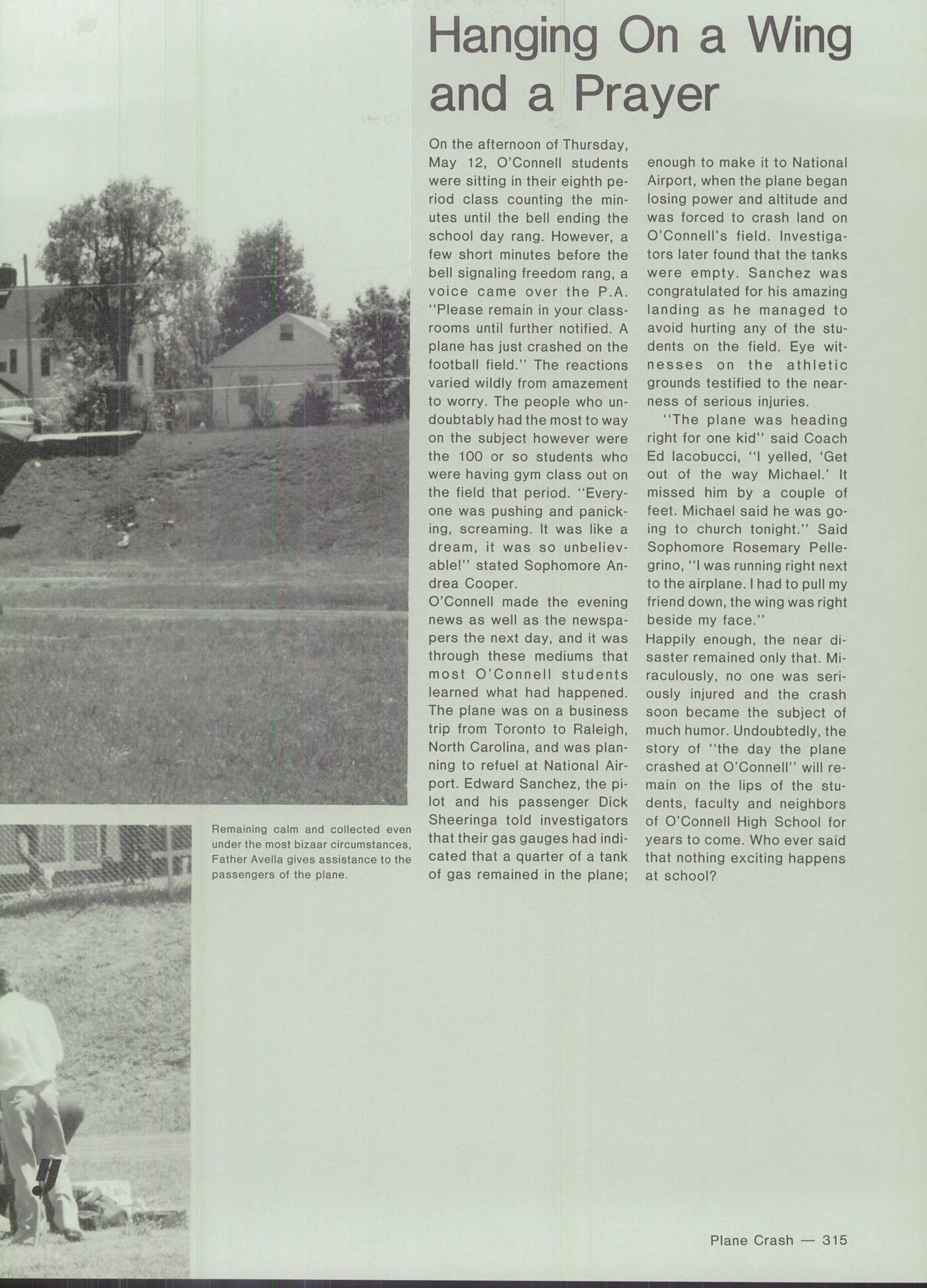

“Kitchen Favorites from the Good Neighbor” was compiled and published by the Arlington County Chapter of the American Red Cross in May 1982 to commemorate the 65th anniversary of the chapter. It’s full of wonderful illustrations by Karen Beasley and was assembled by an army of volunteers. This illustration is for Pot Roast Diablo by Florence Churchill and can be found on page 47.

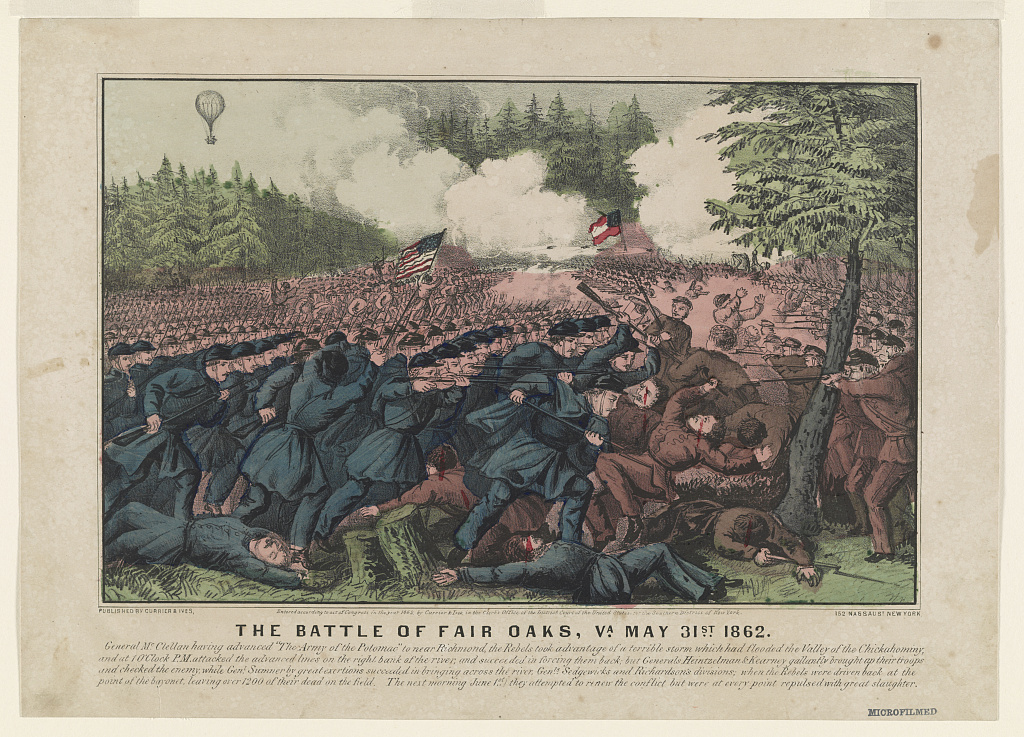

Fundraising through cookbooks has been an American tradition since 1864 when Maria J. Moss published A Poetical Cookbook (so-called because the recipes rhymed for entertainment and easy memorization) and donated the proceeds to subsidize medical costs for Union soldiers injured in the Civil War.

A century later, so many community organizations had taken up the idea that publishing companies began offering custom cookbook services – templates with built-in illustrations, measurement guides, and helpful tips and tricks marketed toward housewives. That said, many of the CLH’s community cookbooks were printed, illustrated, and constructed “in-house,” harnessing the time and talents of dedicated community members.

In addition to fundraising, cookbooks celebrate community organizations and help document their histories and values. For example, Arlington Presbyterian Church made “Table Treasures” in 2008 to celebrate a “Century of Hospitality” since the church was founded on April 12, 1908. They preface their collection of recipes with an introduction that sketches the history of the congregation and draws upon their organizational archives to illustrate the church’s longtime dedication to feeding the soul and body.

“Forest Favorites” was compiled in 1976 by the women of the Miriam Gruber Fellowship at Arlington Forest United Methodist Church. It is bound with wooden covers made by Gene Dauma of the Methodist Men, in keeping with the “forest” theme. The cover illustration was likely done by Betty Quinn, one of the Miriam Gruber Fellowship members.

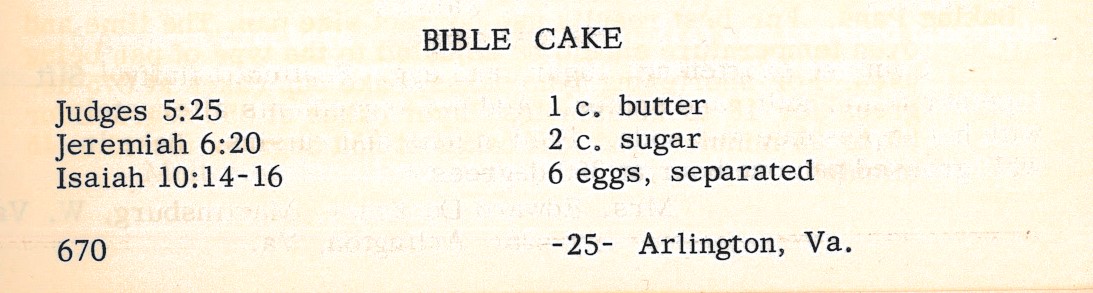

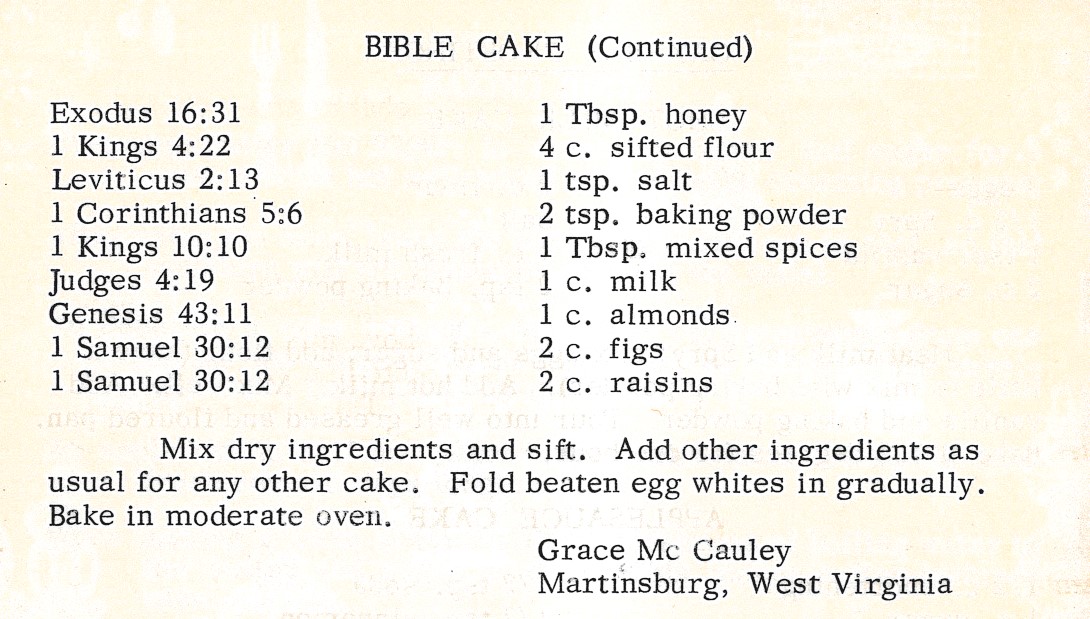

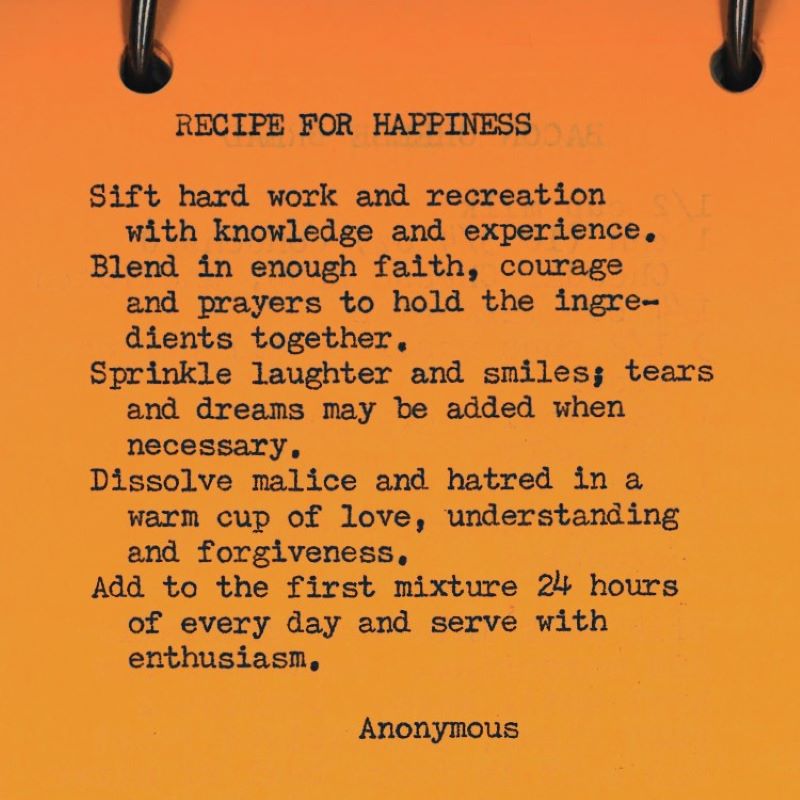

The intimate association between food and faith comes as no surprise, and similar sentiments are found in other church cookbooks that contain recipes for Happiness and tempting cakes inspired by Bible verses.

Most importantly, the CLH’s community cookbook collection preserves the memory of all those who created, perfected, and passed along their beloved home recipes. Most recipes credit their cook, and many are also dedicated to the mothers, grandmothers, church organizers, and community leaders that taught them.

As the Arlington Red Cross puts it in their cookbook, “A recipe that is not shared with others will soon be forgotten, but when it’s shared, it will be enjoyed by future generations.” So please, try out some of the recipes included in this post or stop by to check out what other delicious treats the collection has in store.

Works Cited

All images are from the following cook books in the Library's collection:

- Arlington County Chapter of the American Red Cross, "Kitchen Favorites from the Good Neighbor." 1982. [VA 641.59755 K62a].

- Arlington Forest United Methodist Church, "Forest Favorites." 1976. [VA 641.59755 A724fu].

- Arlington Presbyterian Church, "Table Treasures: Celebrating a Century of Hospitality." 2008. [VA 641.59755 A724t].

- Christian Women’s Fellowship of the Pershing Drive Christian Church, "Our Favorite Recipes." 1962. [VA 641.59755 O93p].

- Clarendon United Methodist Church, "Medley of Morsels." 1986. [VA 641.5 UN58].

Additional Source: Jessica Stoller-Conrad. “Long Before Social Networking, Community Cookbooks Ruled The Stove.” The Salt. July 20, 2012.

Help Build Arlington's Community History

The Center for Local History (CLH) collects, preserves, and shares resources that illustrate Arlington County’s history, diversity and communities. Learn how you can play an active role in documenting Arlington's history by donating physical and/or digital materials for the Center for Local History’s permanent collection.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields