"The Price of a Ticket at the Cost of Your Conscience"

In 1959, Arlington became the first school system in Virginia to desegregate, and in 1960, after a series of organized sit-ins, the County desegregated its lunch counters. But the long road toward full desegregation of public and private institutions in Arlington and Virginia was just beginning, and an important milestone in this journey was Arlington’s movie theaters.

The process to extend equal rights to members of the Black community who wished to attend films and shows in the communities where they lived took three years, the dedication of Black activists, and extended legal battles against the County and the State.

The Right to Equal Enjoyment

In 1960, Arlington's six theaters – the Arlington, Buckingham, Byrd, Centre, Glebe and Wilson - were for the enjoyment of white people only, with no separate areas or alternate local options for Black patrons. Black Arlingtonians had to travel to Prince William County, Washington, D.C., or Alexandria to attend film screenings at integrated theaters.

Alexandria had a single theater open to Black patrons, the Capitol Theater at Queen and Henry Streets, which operated from 1937-1947, and later the Carver-Alexandria Theater, which operated until 1965.

Washington, D.C., had desegregated its theaters in the 1950s following extended boycotting, activism, and legal maneuvering led by Black Washingtonians. In 1950, two integrated theaters opened, and in 1952, the National Theatre (at the center of the integration battle) ceased segregation in its audiences. Finally, in 1953, a U.S. Supreme Court ruling struck down a law that permitted segregation in D.C. restaurants, and this ruling was applied to local theaters as well.

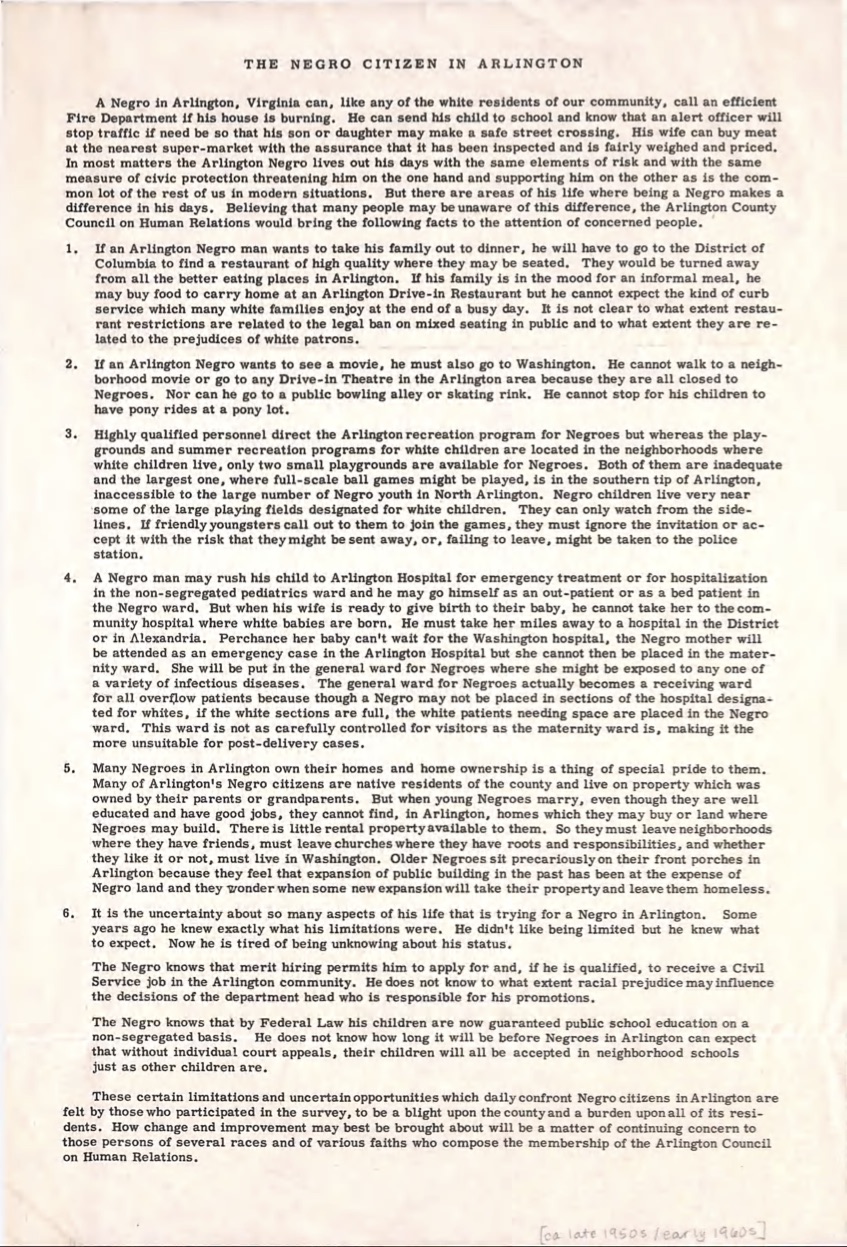

In an undated edition of “The Negro Citizen in Arlington,” published by the American Council on Human Relations, the broadside lays out the various inequities faced by members of the Black community in Arlington. Among the still-existing barriers listed was a lack of access to theaters in item 2: “If an Arlington Negro wants to see a movie, he must go to Washington. He cannot walk to a neighborhood movie or go to any Drive-In Theatre in the Arlington area because they are all closed to Negroes.” From RG 123.

Arlington, however, wouldn’t follow suit for another decade. In an oral history interview with Michael Jones, one of the first children to desegregate Arlington Public Schools, he recalls traveling outside of the County to attend movie screenings:

“At the time, we spent a lot of time going to D.C. because there were no movies. We couldn’t go to the movie theaters there, so we had to catch the bus to go to D.C. to watch movies. That was also something we had to do. It was just life as it was at the time. ... Yeah. Oh, yeah. I mean, we frequently caught the bus on Lee Highway, and it took us right down to D.C. — 11th and E. or the stops where the movie theaters were — so we spent a lot of time going back and forth. No subway then, so we — it was just the un-air-conditioned bus down there with the fans and everything like that.”

The segregation of Arlington’s movie theaters was aligned with other Jim Crow practices that permeated the County's legal system at that time, and were based in segregation law surrounding public assembly and seating.

Virginia’s laws regarding "Separation of Races" in public settings had been adopted in 1926, requiring racially separate seating at any “public hall, theater, opera house, motion picture show or any place of public entertainment or public assemblage.” This law also provided that any proprietor who failed to segregate their audience would "be fined not less than $100 nor more than $500 for each offense” and that any patron of the theater who refused to take a seat in the assigned section or refused to move to the assigned section when requested, "shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor and upon conviction thereof fined not less than $10 no more than $25 for each offense.”

This law had been periodically challenged in local and state courts, but judicial results and the actual local practices differed.

An Arlington judge ruled in 1957 that the segregated seating laws were valid, but in 1958 another judge ruled the law unconstitutional. And though no court had reversed the 1958 ruling, the laws still existed in practice.

Scanned document: Excerpt of Section 18-327 of the Virginia Code, which laid out the laws mandating segregated public assemblies. Image from RG 07, circa 1960.

Around 1960, following the successful desegregation of Arlington’s public schools, local activists directed their attention to the theaters. Civil rights groups initiated a letter writing campaign and conferences to encourage theater owners to bypass these laws, which had been done by other businesses that required public assemblages. The activists encountered only opposition from these campaigns.

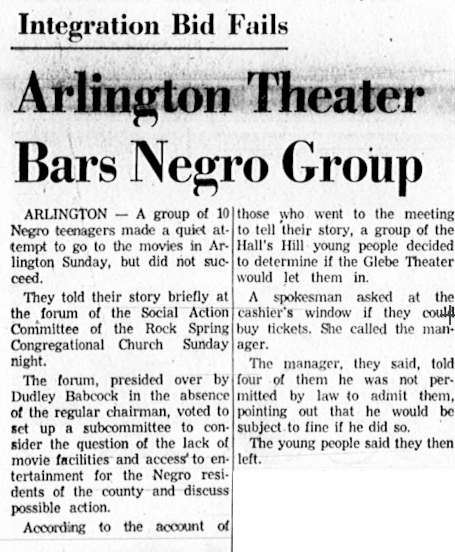

On March 18, 1962, a group of 10 Black teenagers from Hall’s Hill attempted to attend a film in Arlington at the Glebe Theater and were denied entry.

The group reported this experience to the Social Action Committee of the Rock Spring Congregational Church, who agreed to create a subcommittee to address the issue of theaters.

Article from the Northern Virginia Sun on March 19, 1962. Image courtesy of Virginia Chronicle.

The Northern Virginia Committee to End Theater Discrimination was subsequently organized by the Councils on Human Relations of Alexandria, Fairfax, and Arlington to further support theater desegregation efforts.

Picketting Arlington Movie Theaters

Picketing was the next step in the fight, and was also sponsored by the local branch of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Picketing efforts were spearheaded by Dorothy Hamm, who led the picket lines. Hamm was a prominent local activist, and had been deeply involved in the legal and organizational effort to desegregate Arlington Public Schools and eliminate the poll tax.

Pickets were announced by CORE in early May 1962, and began on May 11 at the Glebe Theatre. This theater was selected as it was the site of the offices of Wade Pearson, who managed Neighborhood Theaters, the chain that operated theaters across Arlington and Fairfax.

Dorothy Hamm (1919-2004), who led the Arlington theater pickets. Image courtesy of Carmela Hamm via the Library of Virginia.

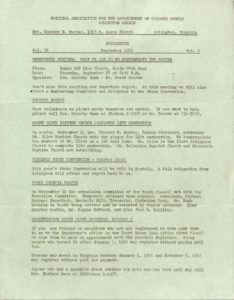

A 1962 pamphlet from the NAACP Arlington branch newsletter calls for participants in the picketing efforts to desegregate Arlington’s theaters. From RG 18.

In late May 1962, the Arlington County Board publicly denied responsibility for initiating integration by not taking an official stand on the segregation of the theaters. After local advocates appealed for public support for integration, Board Members argued it wasn’t within their authority to do so, or believed the decisions should rest with individual business owners (though they claimed to oppose the discrimination on a personal level). In response, individuals later called for a boycott of Arlington theaters in a Letter to the Editor in the Northern Virginia Sun, arguing “only white citizens can economically affect the theater owners by refusing to patronize their theaters.”

Additional pickets began in early June 1962, demonstrating at five of the County’s movie theaters. These protesters were faced with harassment from members from the American Nazi Party (led by George Rockwell and founded in Arlington in 1959), who launched their own counter-picket in response to the calls for desegregation.

A New Legal Barrier is Challenged in Court

Picketing continued throughout the summer, but the protesters soon faced a new obstacle. On June 28, 1962, it was reported that members of the Committee to End Theater Discrimination had been served with a notice by the Arlington Chief of Police that a new law would go into effect on June 30, putting the picketers at risk of arrest.

This amendment to the Virginia Code provided that individuals picketing against theaters and other businesses with the intent to “injure” a business “willfully and maliciously” could be found guilty of a misdemeanor, with a maximum penalty of $1,000 fine or 12 months in jail or both.

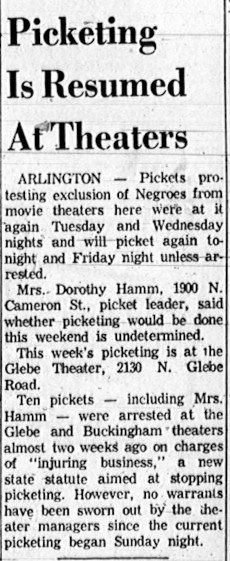

From The Northern Virginia Sun, July 12, 1962. Image courtesy of Virginia Chronicle.

On June 29, and July 1, 1962, 10 protesters were arrested while protesting at the Glebe and Buckingham theaters on the charges of “injuring business" under the new picketing law. Dorothy Hamm was among this group arrested, and all were released without bond. Hamm’s case, along with four others, was initially dismissed by the County Courts on July 2 on a lack of evidence that their actions had halted or injured business. Amidst this legal challenge, picketing paused until July 8, and continued throughout the week.

Meanwhile, the remaining five picketers who had been arrested were charged under all sections of the picketing law. The case then became an attempt to test the constitutionality of the amendment and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) joined to assist in the legal proceedings.

The five individuals were represented in court on July 17 by civil rights lawyer Joseph L. Rauh, Jr., who argued that “How can it be ill will, malicious, wicked or mischievous to tell the public a theater does not admit Negroes, which is true, and to try to get them to change the policy?” and that picketing was a form of protected free speech.

The theaters were represented by Commonwealth’s Attorney William J. Hassan, who had argued the pickets injured the business policies established by the theater, and that the theater was “exclusionary” rather than segregated, as it did not offer even separate seating for Black patrons.

The lawyer Joseph L. Rauh, Jr. (1911-1992), represented the picketers who had been arrested protesting Arlington's segregated theater policy. Rauh was a prominent civil rights lawyer and advocate, and lobbied for the passage of the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Act. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The ruling was initially deferred, and the remaining five picketers were ultimately acquitted on August 14. County Court Judge Paul D. Brown stated that the facts were not sufficient to support a conviction, though it was not necessary to rule on the constitutionality of the law forbidding injury of business.

Change at Last

The next year saw an increase in legal interventions related to movie theaters and public assemblies around the state. In early 1963, theaters in Norfolk, Portsmouth, and downtown Richmond began to desegregate. They were followed by Alexandria theaters in May of 1963, which desegregated its Reed, Richmond, Virginia, and Vernon theaters.

On June 17, 1963, Arlington finally, and relatively quietly, desegregated its theaters.

In a June 18, 1963, Northern Virginia Sun report on the desegregation, the Neighborhood Theaters manager Wade Pearson denied that the theaters had ever been segregated at all, and claimed “the Neighborhood Theaters have never made it a practice of admitting persons to the movies on the basis of religion, creed, or race.” Regardless of this legally contradictory and factually incorrect messaging, the local branch of the NAACP was assured the theater would be integrated as of the June 17 date given by the theater owners.

The Wilson Theater, another of the theaters that was picketed, at 1724 Wilson Boulevard. Pictured in 1940, this photo is from the Arlington Journal, October 5, 1998.

Dorothy Hamm and her son Edward Leslie, Jr., were the first Black patrons to attend a movie theater in Arlington. In this oral history interview, Dorothy Hamm recalled attending the theater for the first time:

Dorothy Hamm: On the first night when it was OK for us to go, my son and I and a white couple were among the ones who went to the theaters.

Edmund Campbell: Any particular incident of interest when you went into the theater?

DH: Well, I wasn't really sure whether they were going to let us in or not, so on that night a white couple and my son and I went to the theater. The white couple purchased tickets, and when I went to purchase a ticket I wasn't really sure whether they were going to sell me a ticket or not. We had prearranged it where I would be given a ticket by one of the white people, and I was going into the theater. However, it happened that we were sold tickets, and my son and I went into the theater with the white couple.

EC: You spoke earlier of Arlington County, or perhaps they were state, seating laws. Now with the theater selling you tickets, was this their own decision or had the seating law been changed?

DH: I don't believe the seating law...well, I'm not certain about that. I do know that it was a decision made by the manager of the theaters. However, prior to this ‑‑

EC: Did you know him? Mr. Wade Pearson?

DH: This was Mr. [Morton] Thalhimer. Prior to this, I had been called by the manager of the Glebe Theatre, and he had indicated even if he gave Blacks separate seating they only had one toilet facility, and separate toilet facilities were also required...

EC: When was that practice of separate toilet facilities abandoned in Arlington? Later?

DH: Yes, it was.

On July 1, 1963, soon after the Arlington theaters opened their doors to Black patrons, Virginia’s seating law was officially struck down. The law had been challenged in a suit filed in February 1963 by two local women, Lillian S. Blackwell of Vienna, and Freddie Lee Harrison of Arlington, after they had been refused entry to the Jefferson Theater in Fairfax and the Glebe Theater in Arlington on account of their race. The women were represented by Noel Hemmendinger (also chairman on the Committee to End Theater Discrimination), and the court first heard the case in May, and by July ruled that the state statute was contrary to the 14th Amendment.

The struggle to desegregate Arlington’s theaters was a labyrinthine process that took immense courage, planning and organizations by the County’s civil rights activists. This achievement was just one milestone in the journey to make Arlington truly equal and equitable for all residents, a journey that continues to this day.

Front page of the Northern Virginia Sun on July 2, 1963. Image courtesy of Virginia Chronicle.

The Center for Local History at the Arlington Public Library collects, preserves and shares historical documents that tell the history of Arlington County, its citizens, organizations, businesses and social issues. The CLH operates the Research Room at Central Library and the Community Archives program.

Because there are always more layers of history to find and examine, the CLH continually seeks community donations and oral histories. Do you, or does someone in your family, have documentation or story to tell related to segregation or desegregation in Arlington?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History or contact us at localhistory@arlingtonva.us.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields