The Stuart Paine Swimming and Diving Collection began with a mystery.

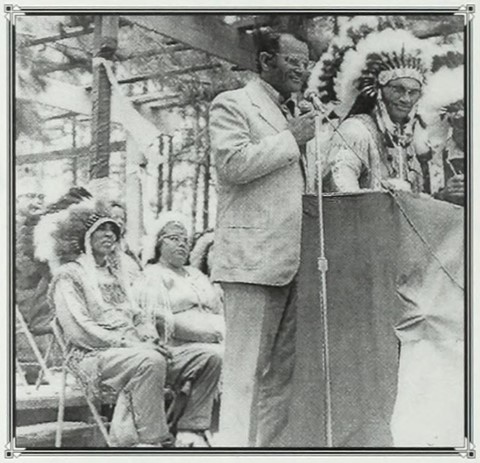

In 1967, at the age of 14, Stuart Paine began diving at the Springboard Swimming Pool in Springfield, VA, and shortly thereafter started participating in meets with the Northern Virginia Swimming League (NVSL). When Paine won first place in the 1968 NVSL 3-Meter Meet, NVSL recorded him as the first winner of the 3-Meter Meet in their official historical record.

However, Paine was present at the same meet the previous year, so he knew he couldn’t be the first person to win the 3-Meter Meet. This meant the official NVSL record was both inaccurate and incomplete.

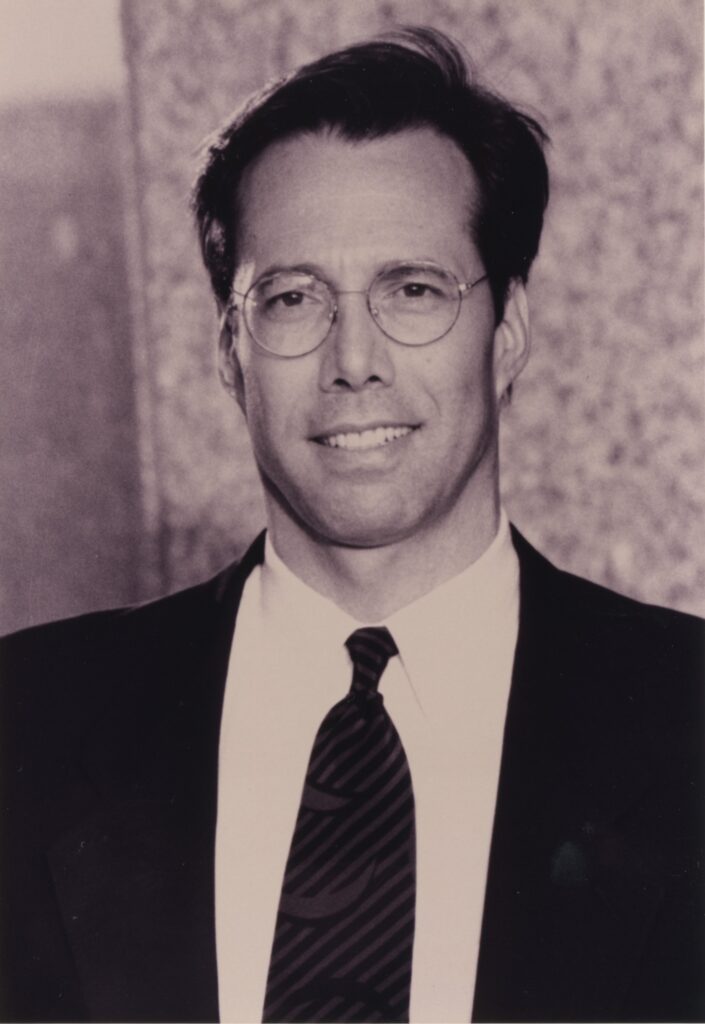

Stuart Paine (bottom row, center) showing off his trophy at the 1969 NVSL meet. From RG 395: Stuart Paine Swimming and Diving Collection.

Realizing the discrepancy, Paine wanted to give earlier NVSL winners the recognition that they deserved. This led him to research the early history of the league as well as swimming and diving in Northern Virginia, Washington, D.C., Baltimore, MD, and nearby areas. In 2016, Paine presented his findings to NVSL in a formal request for them to update their records.

In 2023, he donated this report, along with artifacts such as diving medals, patches and photographs, to the Charlie Clark Center for Local History for researchers to access. We consulted the Paine collection to learn about swimming in Arlington through the years.

Swimming in Arlington before the 1950s

Most people living in Arlington before the mid-20th century swam in natural creeks and rivers. Everett E. Norton, who grew up in Columbia Pike in the 1920s and '30s, used to go swimming at Four Mile Run as a child. Later, he would take trips to Fort Myer to swim at the pool there, which required a membership.

Buckingham Pool House in 1991. The swimming pool complex was integral to the original plan for Buckingham Village, envisioned in the late 1930s as a self-contained community that included recreational, entertainment, and educational facilities. This also meant that the pool house was closed to non-residents of Buckingham.

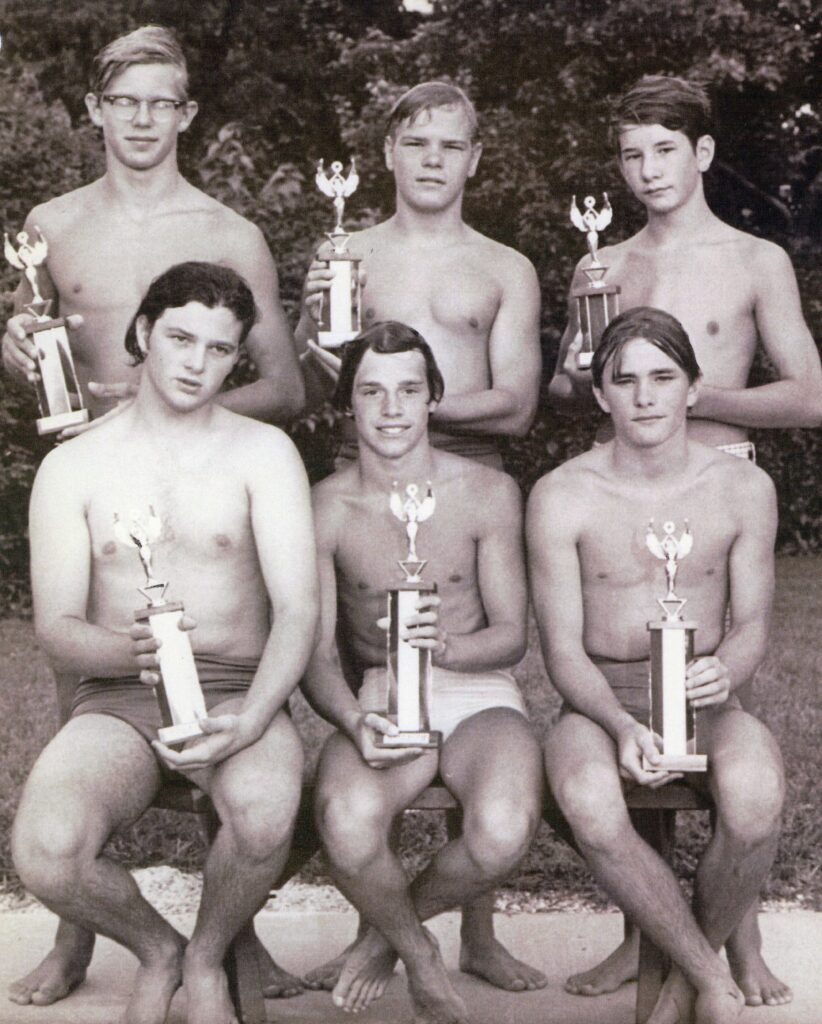

In 1939, with no public swimming pool of its own, Arlington County arranged to transport children to the Washington, D.C., municipal pool in East Potomac Park. Until at least 1947, swimming sessions were segregated by gender. In 1950, Arlington began sending buses of Black children to East Potomac Park for desegregated swimming. Until then, only white children were permitted.

Several children lined up to board a school bus to go to a public swimming pool in D.C. From RG 32: Documents from the County Manager's Library, 1889-1994.

Opening Pools in Arlington

The era of Northern Virginia community pools began in the summer of 1953 with the opening of Bradlee Towers Pool in Alexandria and Holmes Run Acres in Falls Church. A boom of swimming pool developments followed. Arlington gained its first community pool in 1955 with the opening of the Arlington Forest neighborhood pool.

When Ruth Cocklin moved to Arlington from California in 1954, she was surprised to find that Arlington didn’t have many swimming pools. Because they had few safe and accessible places to learn, many children didn’t know how to swim. Cocklin came together with her neighbors to establish a swimming pool for their neighborhood, which became the Donaldson Run Swimming Pool.

COCKLIN: “Another thing that I was surprised to find is that a lot of the children (and these were from middle-class families - from professional parents) didn't know how to swim; there was no place to swim. Arlington had no swimming pools.

We belonged to the Fort Myer club, but a number of people in our neighborhood, headed up by Julian Serles and Bob Kovaric and Allan Dean – and my husband was involved with this, Ken Weaver was another one – worked to start a swimming pool for our neighborhood...This became the Donaldson Run Swimming Pool, perhaps the most beautiful one that exists today in Arlington, although there are several neighborhood pools.

The Arlington Forest, I think, was the first one and Donaldson Run was the second, and it took a long time. There was talk of putting it on land on Military Road and the neighbors rose up in horror at that. Eventually they settled on this site on Marcey Road which was at that time a little separated from other people. But the people on Birchwood Place were sure that they were going to be overwhelmed with traffic and it took several years to get it through. And I think the pool finally opened in 1958 and that was a boon.

My children knew how to swim, but a lot of these youngsters simply didn't know a thing at all about it. And I personally think swimming is one of the things everybody should learn, basic swimming at least. Whether you get involved in racing or anything, is another thing.”

INTERVIEWER: “There are three or four of those neighborhood association pools.”

COCKLIN: “Arlington Forest, Overlee, and I think there are a couple of others in Arlington, I'm not sure. But there have been others out in McLean. They still are very, very popular and have long, long waiting lists.”

As new pools continued to open, the Northern Virginia Swimming League was established in May 1956 to organize swim and dive meets among competitive youth representing pools across the area.

The 1950s also marked the establishment and expansion of high schools in Arlington, many of which had swimming pools and swim teams of their own. Wakefield, Yorktown , and Washington-Lee (now Washington-Liberty) all had competitive swim teams by the 1960s. By 1969, all Arlington high schools were desegregated, as were their swim programs.

What’s your favorite place to go swimming in Arlington? Leave a comment and let us know!

Sources

RG 395: Stuart Paine Swimming and Diving Collection, 1892-2023.

Interview with Ruth C. Cocklin. Full transcript online.

Interview with Everett E. Norton. Full transcript online.

Library of Congress: Buckingham Apartment Complex.

Arlington County Website: Buckingham Village Historic District.

Help Build Arlington's Community History

The Center for Local History (CLH) collects, preserves and shares resources that illustrate Arlington County’s history, diversity and communities. Learn how you can play an active role in documenting Arlington's history by donating physical and/or digital materials for the Center for Local History’s permanent collection.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields