Finding Home Away from Home

Oral histories are used to understand historical events, actors, and movements from the point of view of real people’s personal experiences.

Anhthu Lu was born in Vietnam and immigrated to Arlington after the fall of Saigon in 1975. From roughly 1975-1980, the U.S. population of Vietnamese immigrants - many of whom were refugees - had grown from 15,000 to 245,000.

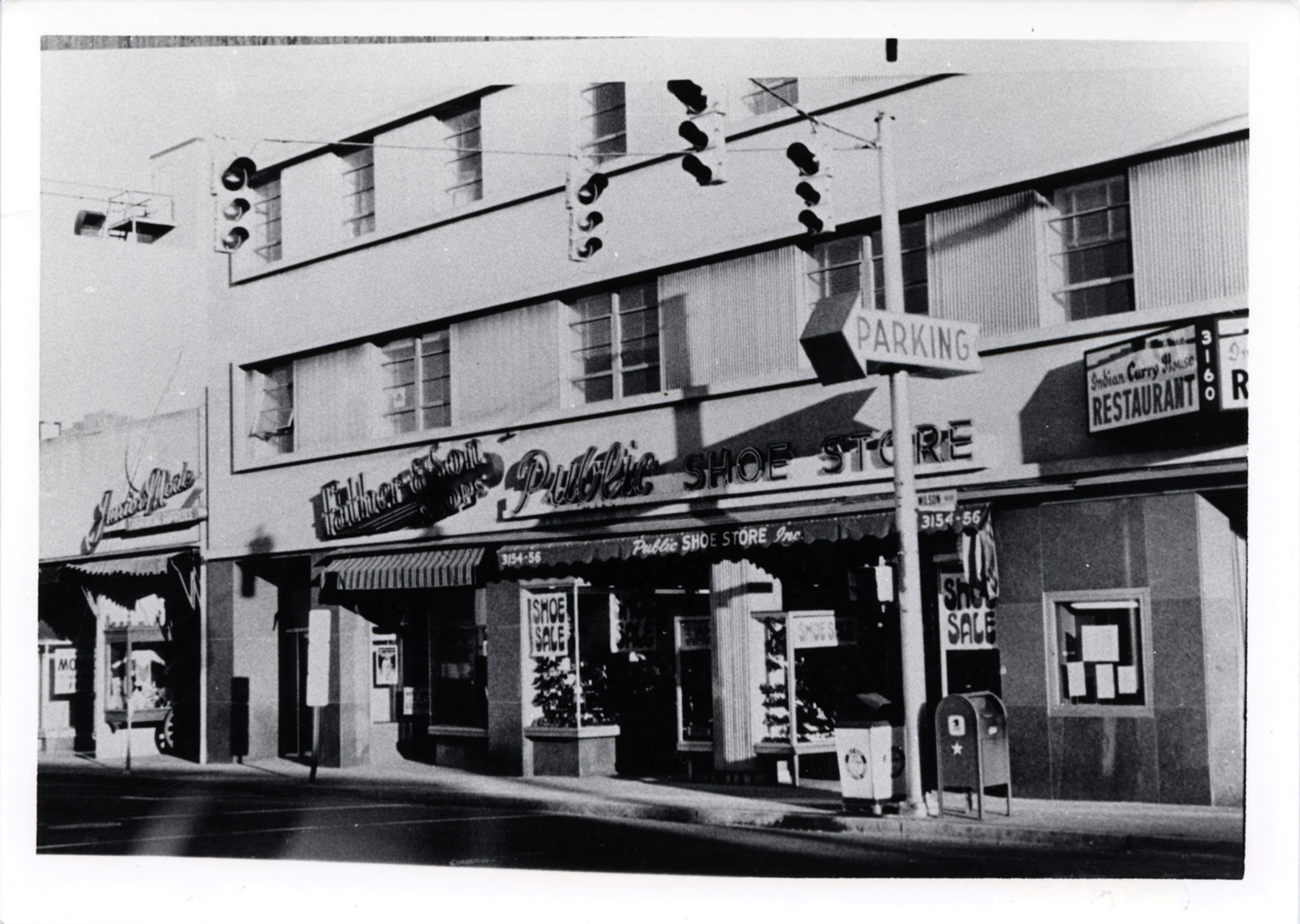

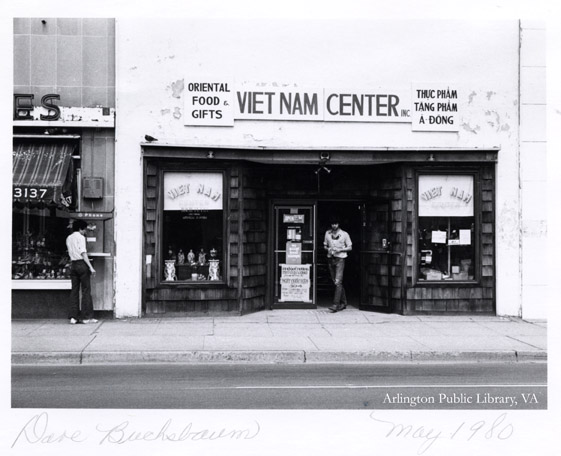

At the same time, the Clarendon neighborhood transformed from a declining shopping destination to a supportive and bustling Vietnamese enclave that became known as "Little Saigon," brimming with stores that provided both imported goods and a sense of community for Vietnamese-Americans.

In a 2016 interview, Lu described the harrowing account of her family's escape from Saigon, as well as the difficult journey from resettlement camps in the Philippines to become settled in Arlington.

In the following excerpt, Lu talks about her reaction to Little Saigon and the positive affect that it had on her as a young refugee:

Narrator: Anhthu Lu

Interviewer: Kim O'Connell

Date: March 16th, 2016

AL: Our eyes lit up. We went in there, and for the first time, you can hear the Vietnamese language and see the Vietnamese products, and things that we know, and things that we need, and things that we knew all our lives. I saw the fish sauce, and the rice paper, and all of the spices and stuff like that. We were like, "so there will be a chance we'll have Vietnamese food again."

The name "Little Saigon" didn't enter our mind until Little Saigon in Southern California started to come up, and then that became like a trademark for wherever the Vietnamese-Americans are, and it became Little Saigon. But at that time, we just called it the Vietnamese market. So at the end of the week, "Are you going to the Vietnamese market?" And it's understood that once you go out there, you have more chances to run into all your friends and family... it's become an oriental area for the Vietnamese people to go...And you can speak in Vietnamese, and totally feel like you're in Vietnam.

It felt really safe. It's like something that you know, and so you're comfortable with it. You feel like, "Oh, if I go there, that's my town." Home away from home. Once you feel that, you start to feel like you're already established here, and you've started to feel comfortable. And from there, you open the door out to bring in more of the way of life here in the US, and the way of thinking...For people like my parents or older people to go there and they have such a language barrier, that they feel more comfortable in an enclave of just Vietnamese. When they go there and start feeling comfortable, they can start speaking a little bit of English here and there, and they start to feel like, "Oh, I'm opening up more to take in a different culture than what's mine."

You can find the entire transcript in the Center for Local History - VA 975.5295 A7243oh ser.12 no.13: Book a Research Appointment.

The goal of the Arlington Voices project is to showcase the Center for Local History’s oral history collection in a publicly accessible and shareable way.

The Arlington Public Library began collecting oral histories of long-time residents in the 1970s, and since then the scope of the collection has expanded to capture the diverse voices of Arlington’s community. In 2016, staff members and volunteers recorded many additional hours of interviews, building the collection to 575 catalogued oral histories.

To browse our list of narrators indexed by interview subject, check out our community archive. To read a full transcript of an interview, visit the Center for Local History located at Central Library.

![Flying White House Reproduction image of a National Archives print that reads: A full view of the four-motored Douglas C-54 skymaster dubbed the 'Flying White House', an ATC transport specially built for President Roosevelt. It has flown over 44 countries and established six world records since it was put into service exactly a year ago [1944]. Seven pilots are seen walking in front of the plane. 1945, 1 print, b&w, 8 x 10 in..](https://library.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/13-5081_original_-1-scaled.jpg)