Oral histories are used to understand historical events, actors, and movements from the point of view of real people’s personal experiences.

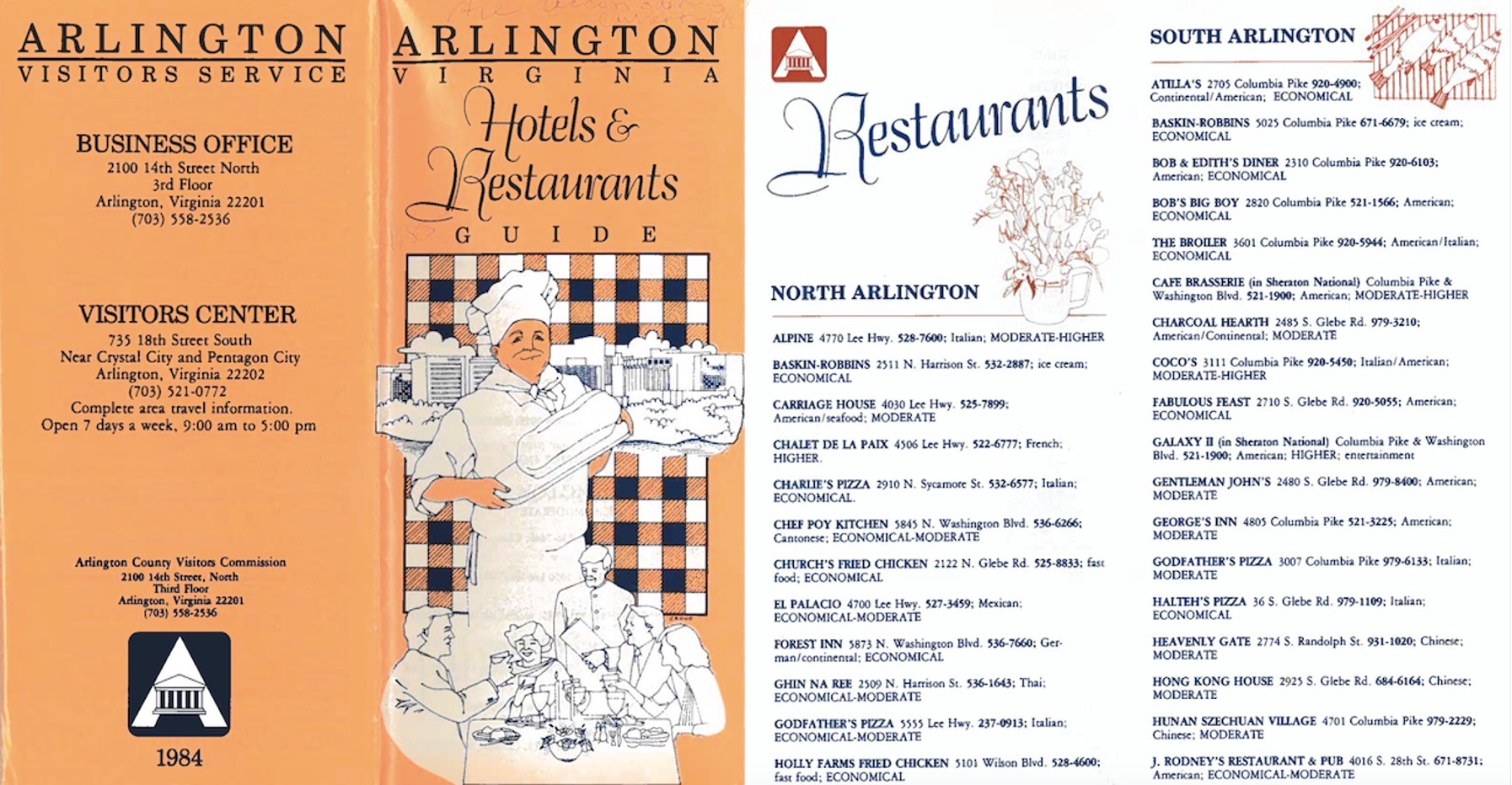

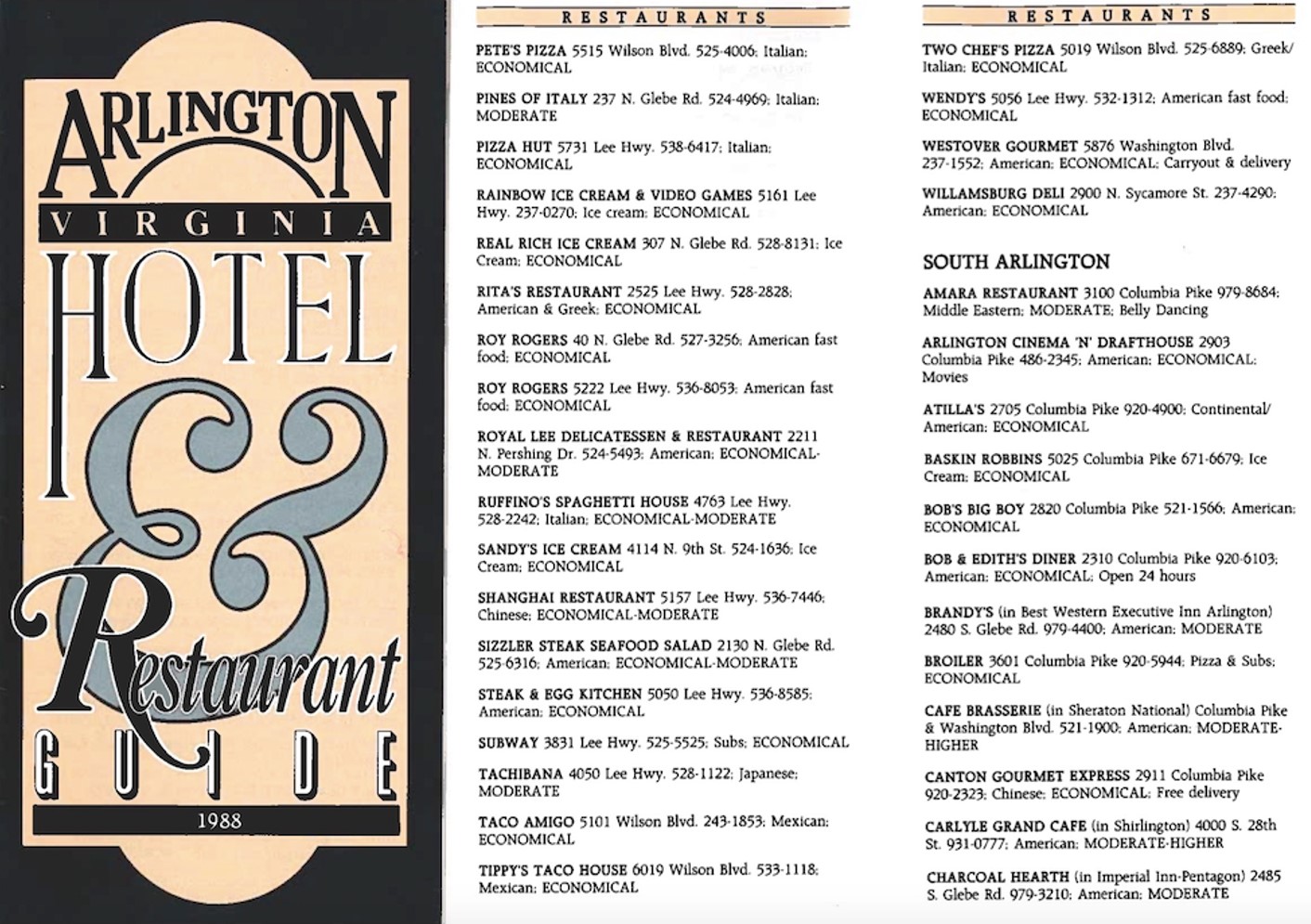

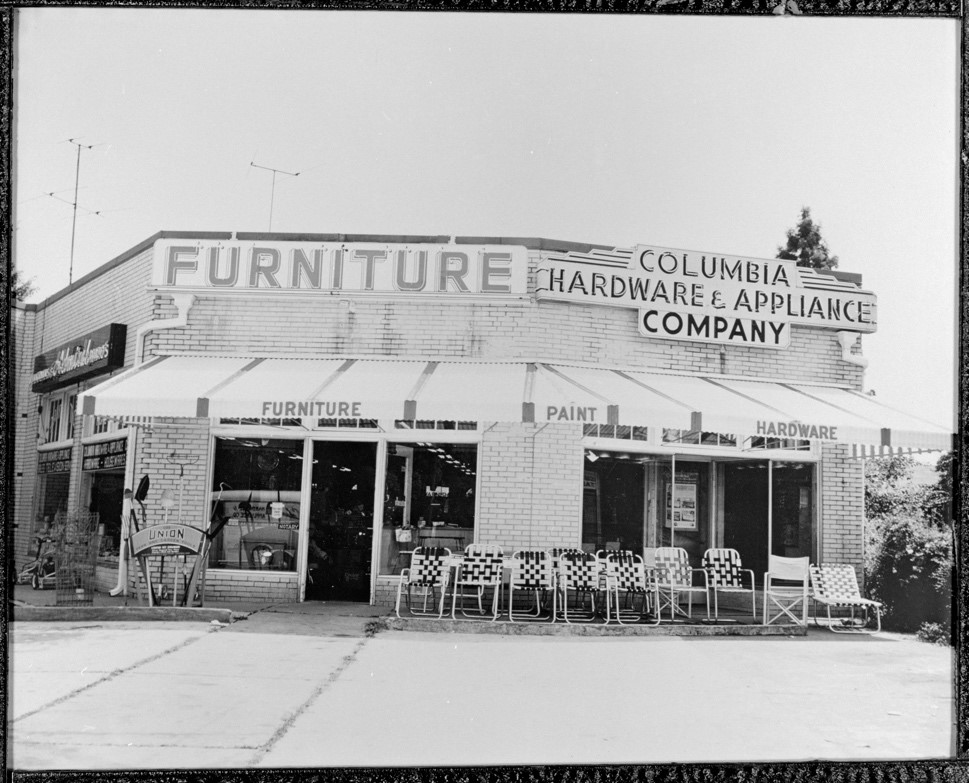

Bob & Edith’s Diner has been an Arlington mainstay for more than 50 years. Established in 1969 by Bob and Edith Bolton, the original Bob & Edith’s got started when the couple took over the location of a “Gary’s Donut Dinette” for $800. The diner started with simple Southern dishes, such as country hams, scrapple, bologna, bacon, and country breakfasts.

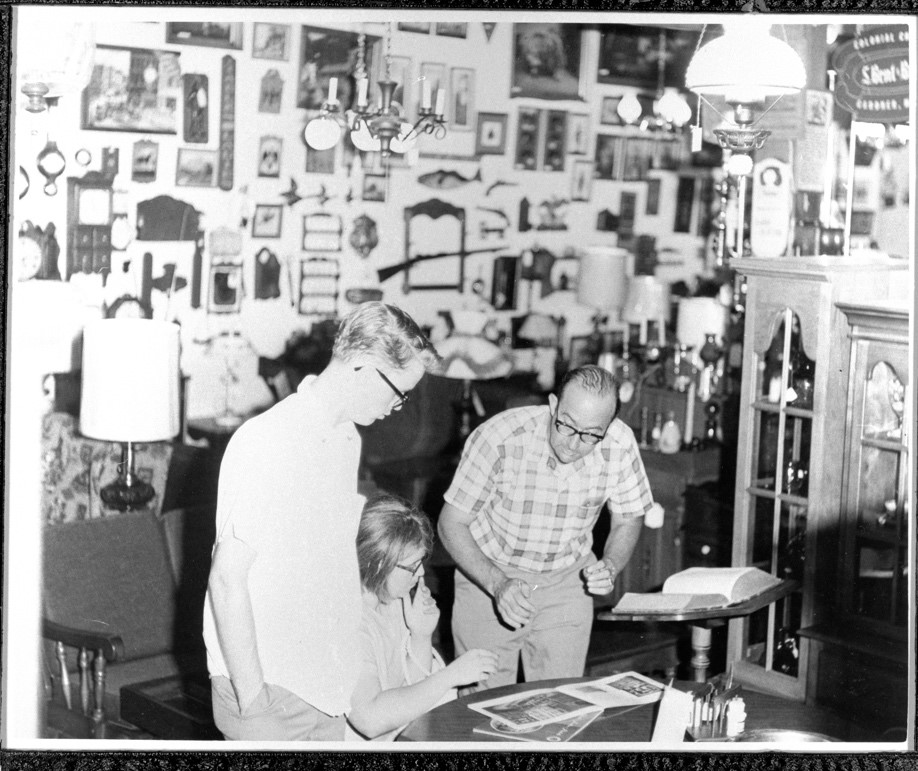

The Boltons later added several locations in addition to the flagship diner on Columbia Pike, and in 1982, the diner expanded from a 10-stool counter to 5 stools and 7 booths. The interiors include many photos of the Bolton family, as well as Dallas Cowboys ephemera and a jukebox.

“Color shot of Bob & Edith’s Diner,” 2010. Photo by Muna Abdulkader as part of the “Capturing Arlington” photo contest.

In this oral history interview, Bob and Edith’s son Gregory Bolton describes the history and operations of the diner and its expanding menu. Today, his son and daughter, Christopher and Tamara Bolton run Bob & Edith’s, continuing the family tradition.

Narrator: Gregory Bolton

Interviewer: Virginia Smith

Date: December 19, 2011

Gregory Bolton: When I was growing up, there was no such thing as really a menu. What there was—above the, in front of the ten stools that were there, and above the grills, there were just signs, such as The Serviceman’s Special. We’d have an artist that would paint these signs up, roughly around sixteen inches, by maybe twenty inches. And it would, for example, would have a serviceman eating a chipped beef breakfast, that we would call it SOS, Serviceman’s Special. And each product was put across the front of the diner, and that’s how you would choose what you would like. There was no hand menu; it was across the board. And we’d replace them like once or twice a year.

Virginia Smith: And then when did you go to a menu, a printed menu?

GB: We probably went to a menu, I would say maybe about twenty-five years ago. The first ten or fifteen years it was pretty much all up in front of you; you picked it out, different ideas and different products. But the menu’s ten, fifteen times larger now than it was back then.

VS: Yeah. Did you get people coming down from the Pentagon?

GB: Yes ma’am. We had Pentagon, and the Navy Annex are very big customers. We had a lot of servicemen. I would say it’s seventy-five, eighty percent is government-related, whether it’s the County, state, Pentagon—

VS: Well, it’s affordable.

GB: —The military. They seem to be very pleased with the operation, and they keep coming back.

“The original Bob & Edith’s Diner,” 2010. Photo by Matthew Welborn as part of the “Capturing Arlington” photo contest.

The goal of the Arlington Voices project is to showcase the Center for Local History’s oral history collection in a publicly accessible and shareable way.

The Arlington Public Library began collecting oral histories of long-time residents in the 1970s, and since then the scope of the collection has expanded to capture the diverse voices of Arlington’s community. In 2016, staff members and volunteers recorded many additional hours of interviews, building the collection to 575 catalogued oral histories.

To browse our list of narrators indexed by interview subject, check out our community archive. To read a full transcript of an interview, visit the Center for Local History located at Central Library.