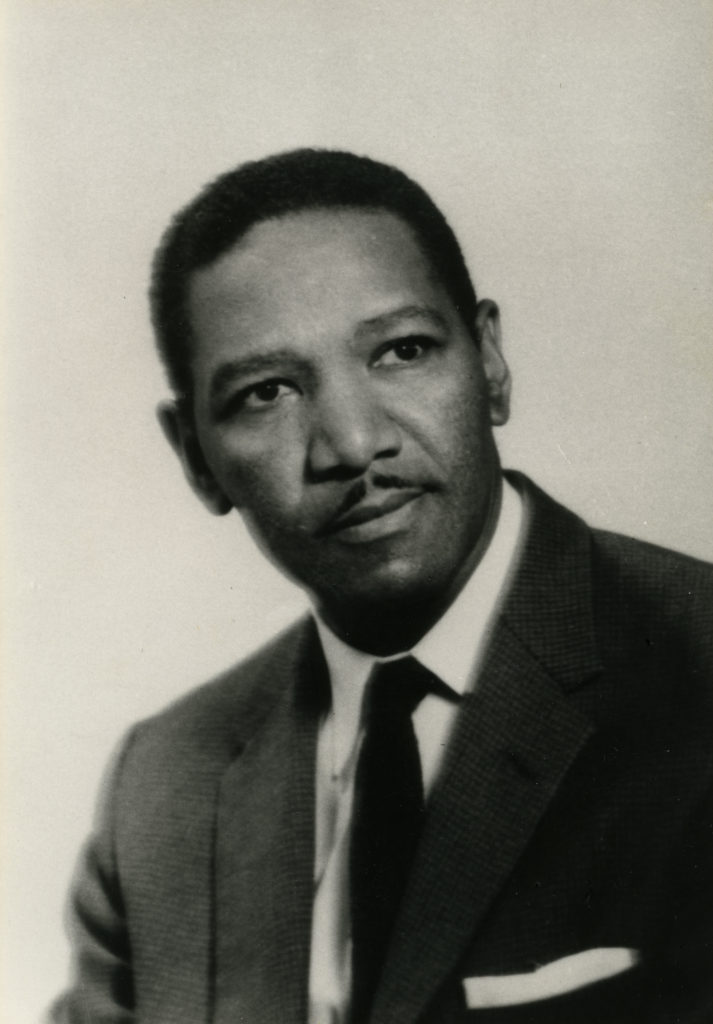

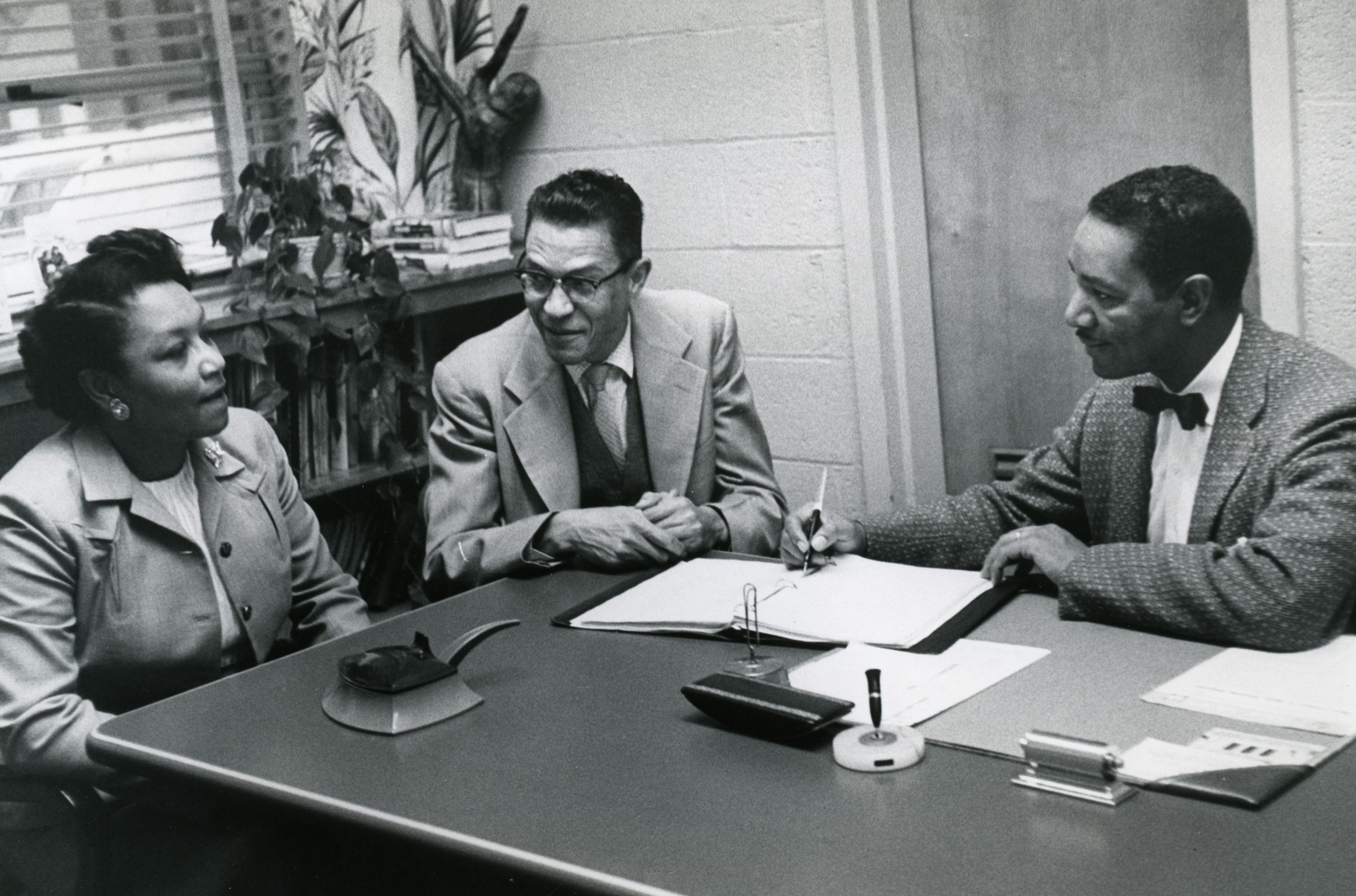

Earlene Green Evans grew up and attended public schools in Arlington, Virginia, graduating from Hoffman-Boston High School. She received a B.S. degree from Saint Paul’s College in Lawrenceville, Virginia, and an M.S. degree in Library Media from Virginia State University. She worked as a middle and high school librarian until she retired.

Earlene authored a children’s book, "I Love You, Ugly Old Hag," and co-authored three educational books. They are "A Step Beyond: Multimedia Activities For Learning American History"; "Hidden Skeletons and Other Funny Stories," and "3-D Displays For Libraries, Schools, and Media Centers."

Earlene is a member of Pi Lambda Theta International Honor Society, Virginia Museum of History and Culture, Northwoods Civic Association, Virginia State Alumni Association, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., and several committees at her church. In addition to writing, Earlene enjoys reading, sewing, and playing the flute. She lives in Henrico County, Virginia with her husband, Alga. They have two adult children and a grandson.

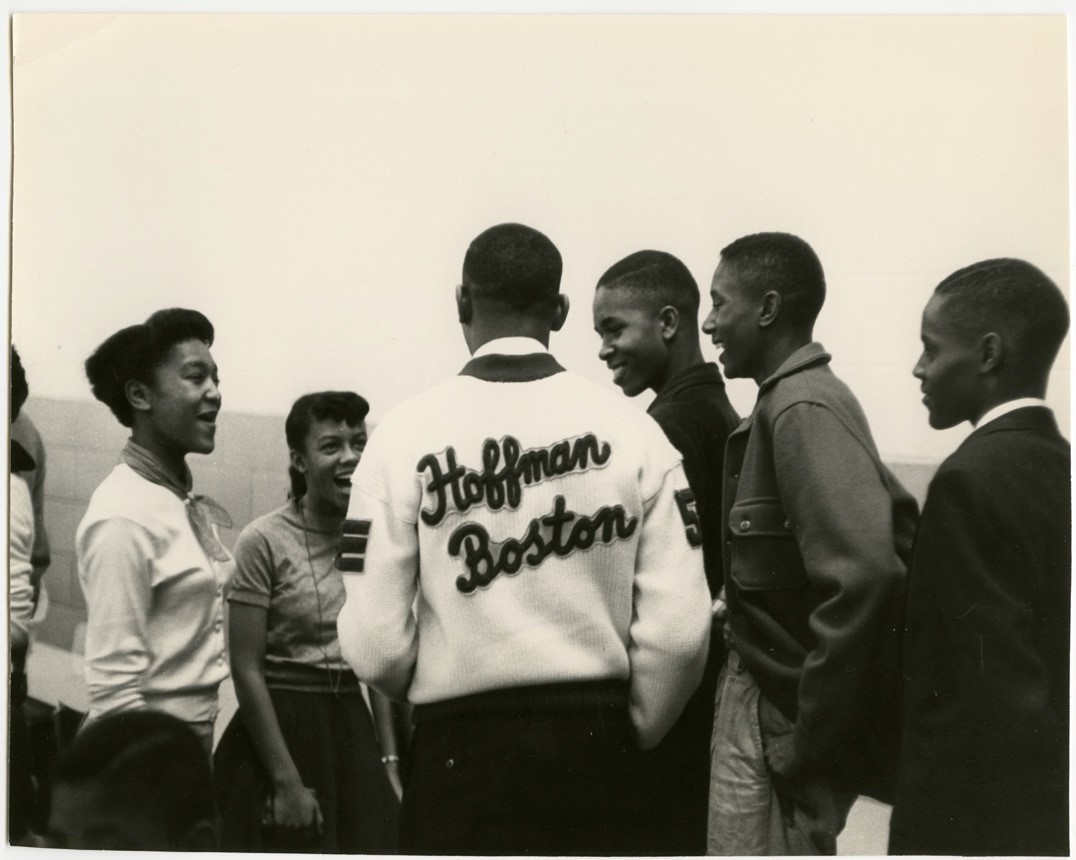

First AKA Cotillion 1958. Image Caption says "Sponsored by Zeta Chi Omega (Arl. VA) First Cotillion, 1958. Earlene Far Right. Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority.

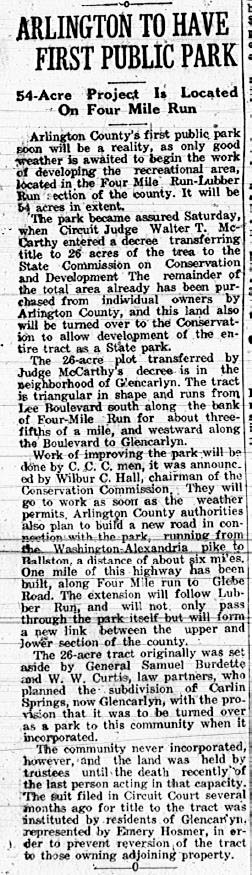

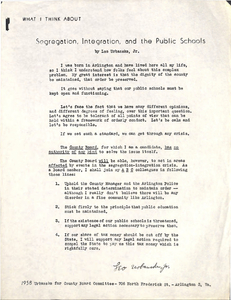

Earlene Green Evans started writing the poems about four years ago, and continued to add others to the collection as time went by. Her latest poem was written in 2019, and she still gets ideas for other poems to this day. Ms. Green writes with wit and charm about what it was like growing up during the fifties in Johnson’s Hill (now Arlington View), a predominantly African American neighborhood at that time.

She describes the general feeling of cooperation and respect among neighbors and the good manners expected from every child; reflects on the influence that radio and television had on families, describes what school was like, popular fashion trends, what was important in the news both locally and nationally as well as what young people did for fun.

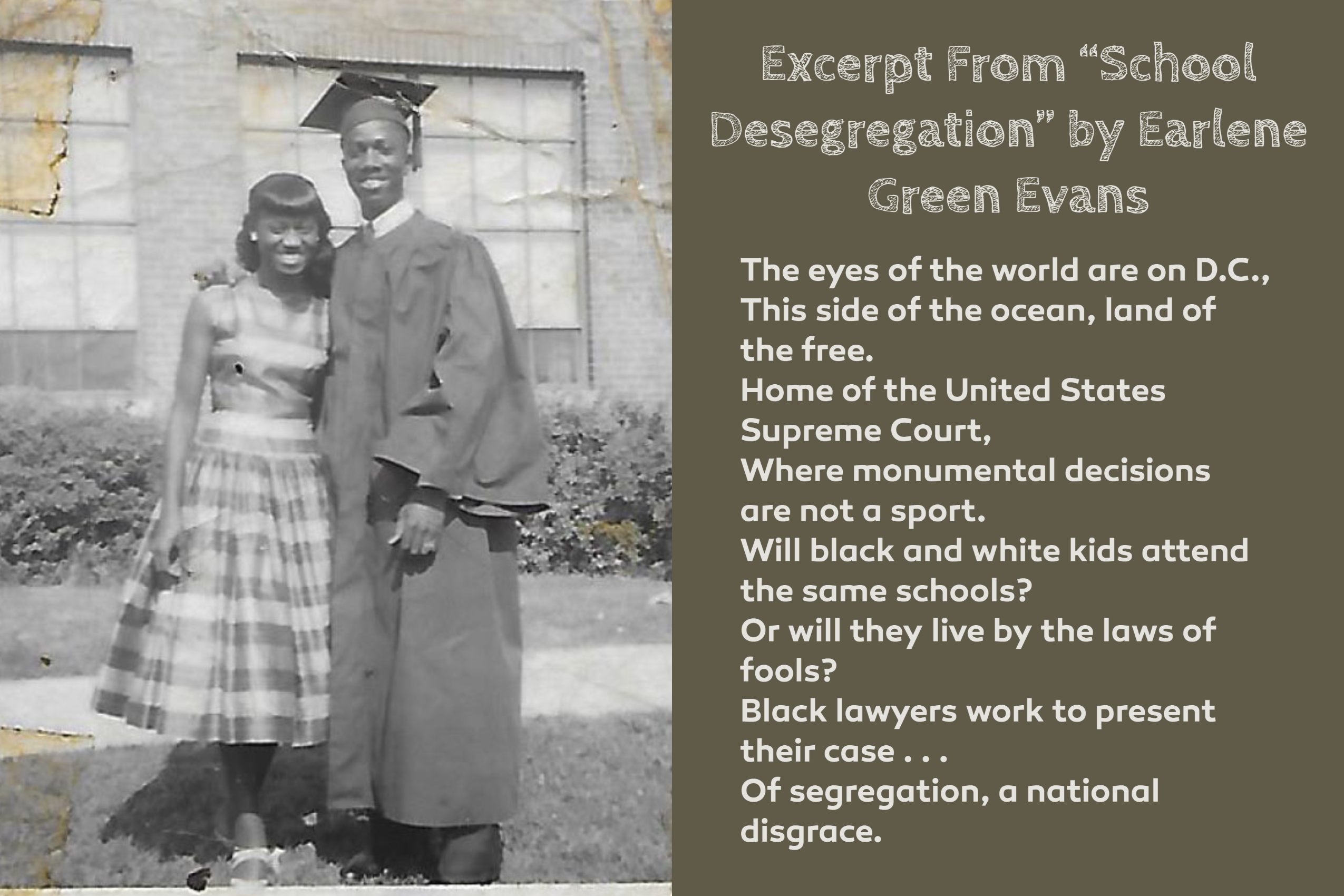

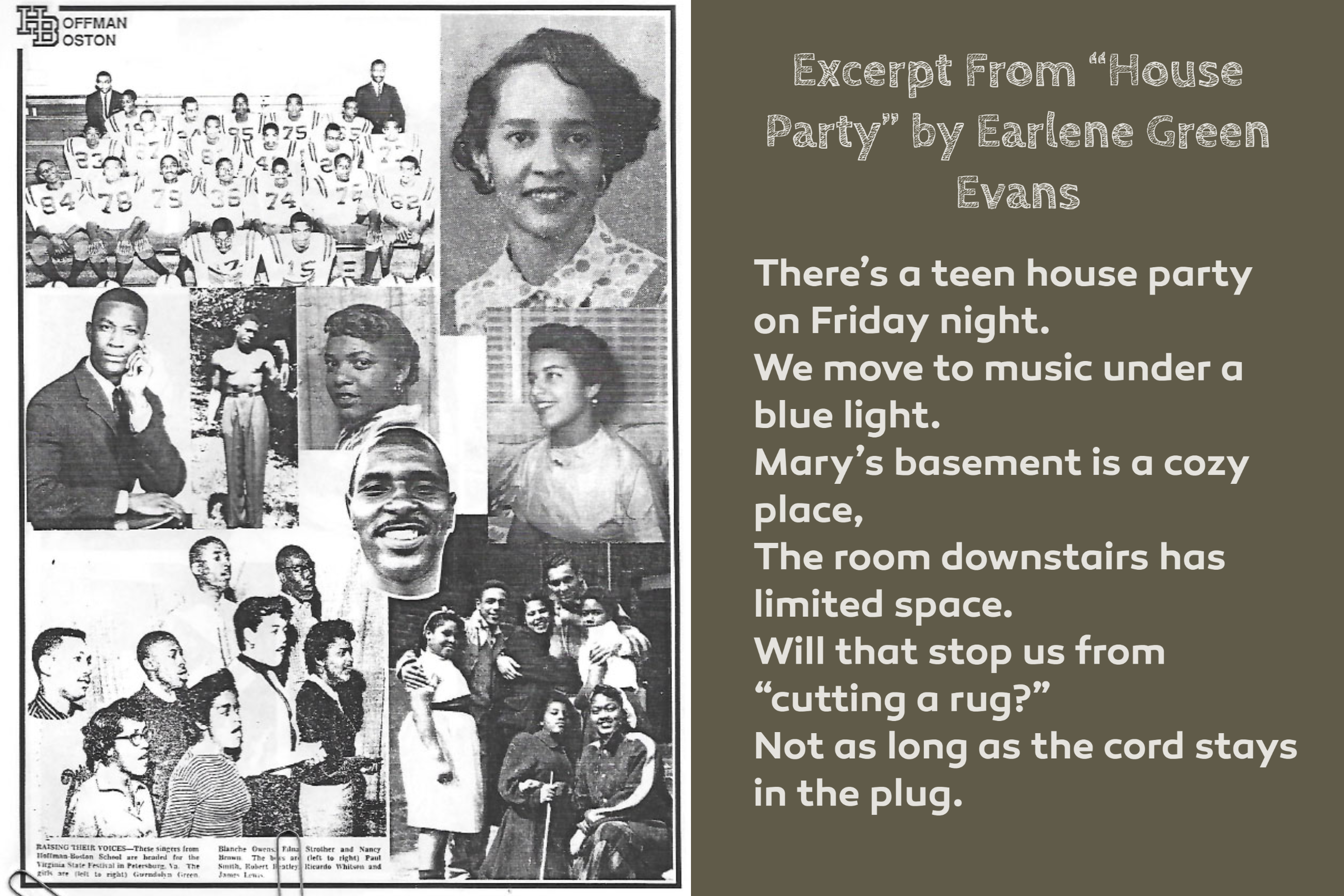

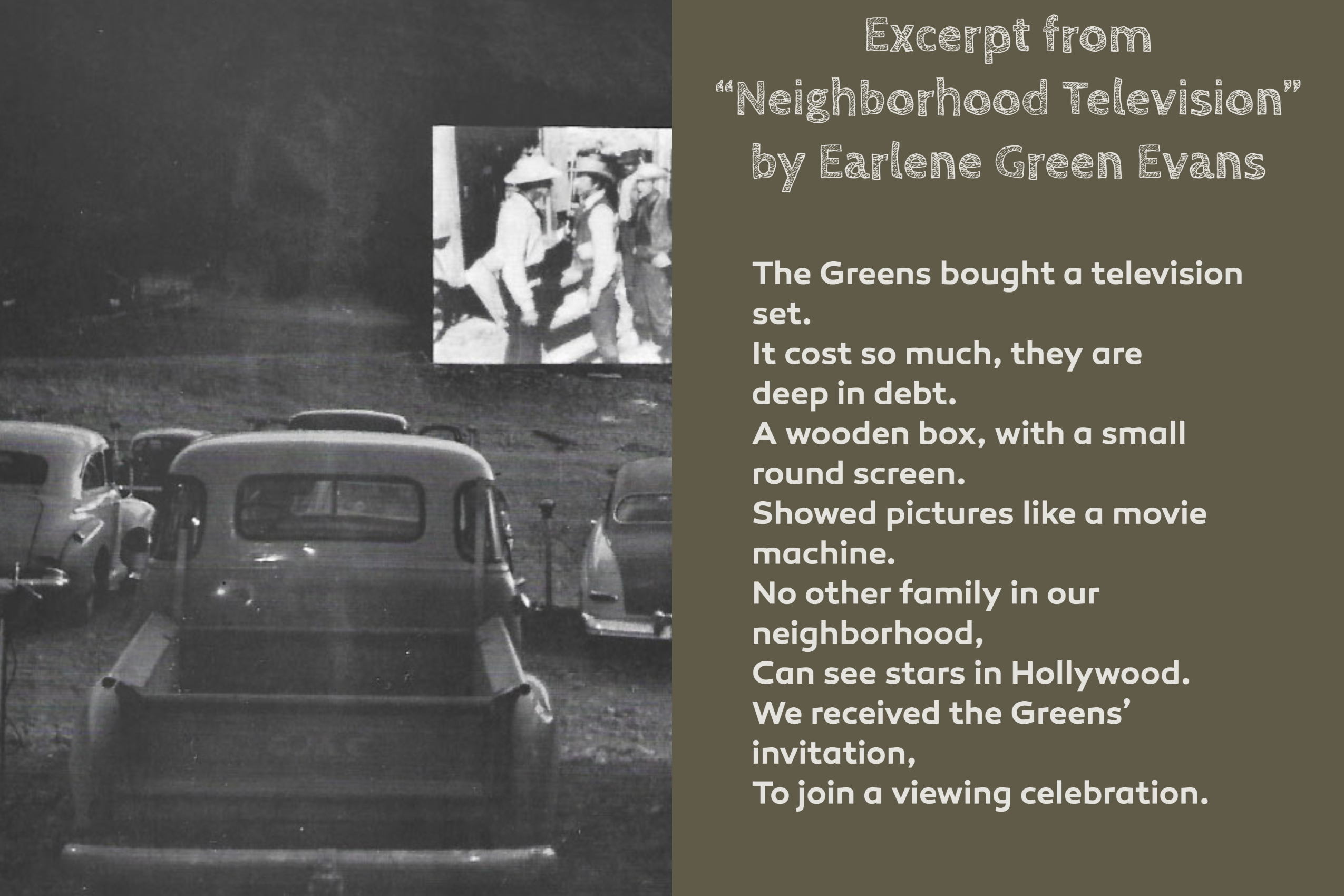

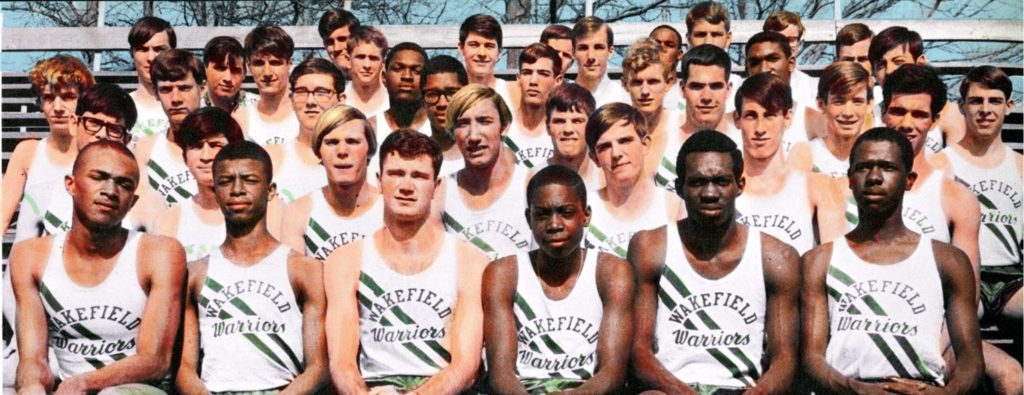

In the following poems from her upcoming poetry book, learn what it was like to go to Hoffman-Boston during "School Desegregation", what it was like to attend a high school “House Party,” and having the first “Neighborhood Television" set.

School Desegragation

The eyes of the world are on D.C.,

This side of the ocean, land of the free.

Home of the United States Supreme Court,

Where monumental decisions are not a sport.

Will black and white kids attend the same schools?

Or will they live by the laws of fools?

Black lawyers work to present their case . . .

Of segregation, a national disgrace.

Separate, but equal cannot proceed,

Equality, regardless of race or creed.

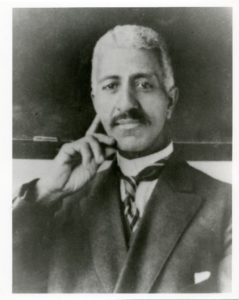

Spottswood Robinson, Thurgood Marshall and Harold Boulware,

Aim to reverse racial laws, declaring them unfair.

They are key lawyers to Brown versus the Board,

This terrible situation will not be ignored!

A decision is made by the nine in black,

That segregationists are on the wrong track.

Now, every black child in any public school,

Will benefit from this constitutional rule.

Thanks to the judges of the highest court,

Thanks to the lawyers who challenged and Fought.

House Party

There’s a teen house party on Friday night.

We move to music under a blue light.

Mary’s basement is a cozy place,

The room downstairs has limited space.

Will that stop us from “cutting a rug?”

Not as long as the cord stays in the plug.

We bump each other, but we don’t mind,

During the “Mashed Potatoes,” and the forbidden “Grind.”

The “Uptown,” and the “Bird Land” are favorites too,

Performed by members of a Rock and Roll crew.

A scratched record makes an ugly repeat,

Moving the head forward makes the song complete.

Refreshments are provided by Pam and Jade,

We have homemade cookers and lime Kool-Aid.

Everyone stops for a kissing game,

“Spin the Bottle” and hope for your “flame.”

Dancing continues, fast and slow,

Cheers to the couple who “takes the floor.”

The party is fun until Mary’s parents appear,

And remind us that the end is near.

On the last record, we do a slow-moving dance,

And steal a little kiss, taking a chance.

Then tell Mary, our house party host,

We enjoyed the evening to the utmost!

Neighborhood Television

The Greens bought a television set.

It cost so much, they are deep in debt.

A wooden box, with a small round screen.

Showed pictures like a movie machine.

No other family in our neighborhood,

Can see stars in Hollywood.

We received the Greens’ invitation,

To join a viewing celebration.

We gladly accepted and rushed next door.

Neighbors were sitting all over the floor.

The large crowd squeezed one another,

Lacking air, we thought we would smother.

Bodies were twisted, and turned just right,

To behold a show in black and white.

Eyes bulged and mouths dropped wide.

To see what a TV would provide.

The Lone Ranger chased a mean outlaw.

We joined the action with a big, “Hurrah!”

He took out his lasso, aimed it, and threw,

As zigzag lines interrupted our view.

Mr. Green turned knobs from left to right,

The lines on the screen were an awful sight.

We were calm and patient; we had to wait.

After a minute, the picture was straight.

The lasso missed as the picture started to roll,

This interruption was harder to control.

Frustrated, Mr. Green turned different knobs.

We shifted, squirmed, and suppressed our sobs.

When the rolling stopped, we read on the screen,

Words that could spark a mad mob scene.

The message was clear, it made us shriek . . .

“Tune in to The Lone Ranger again next week!”