"Project DAPS"

The richly documented story of public school desegregation in Virginia will be made accessible online by the County that led the way.

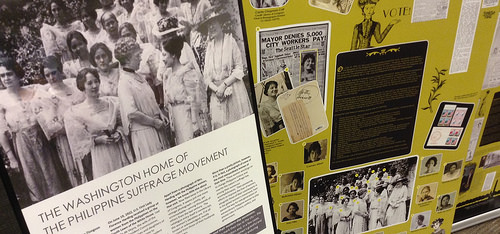

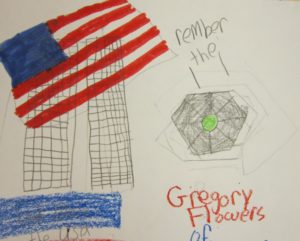

On Saturday, Feb. 25, in conjunction with the 2017 Feel the Heritage Festival, Arlington Public Library launches Projectdaps.org, a unique online exhibition and searchable database – built from thousands of photos, documents and recordings – surrounding the legal and moral battles that culminated with four courageous African American students taking their seats on Feb. 2, 1959 at Arlington’s Stratford Junior High School.

Ronald Deskins, Michael Jones, Lance Newman, and Gloria Thompson walked into Stratford Junior High School on February 2, 1959. Center for Local History, Arlington Public Library

“Project DAPS” (Desegregation of Arlington Public Schools) is culled from the holdings of the Library’s Community Archives in the Center for Local History (CLH) at Central Library.

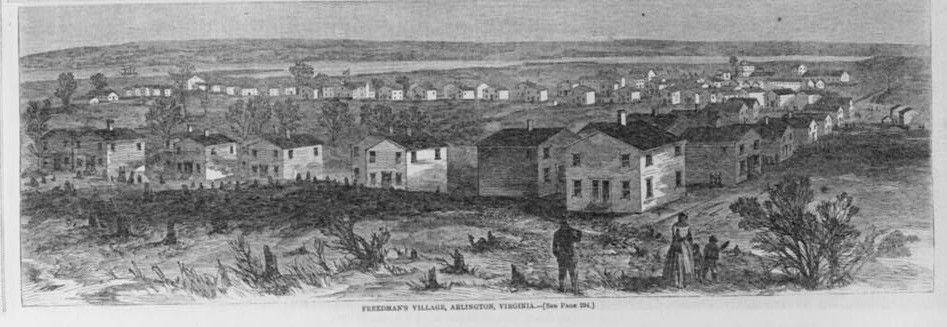

The project explores the historic narrative starting with early integration efforts amid Arlington’s rapid growth of the 1940s. Many items were recently digitized for the first time.

In 2016, the Stratford school property was declared a local historic district. Library Director Diane Kresh says the timing was perfect for creating a “complementary and comprehensive digital collection to tell the story of this signal milestone in our rich community history.”

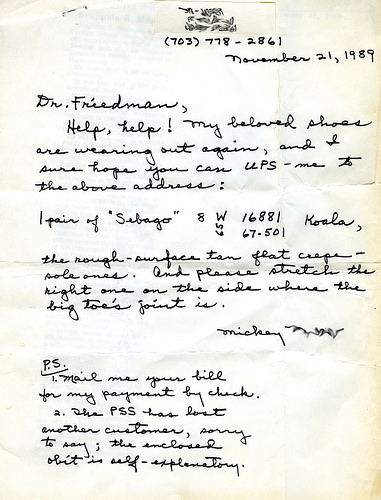

Because there are always more layers of history to find and examine, the CLH continually seeks community donations and oral histories, particularly as they relate to desegregation following the historic day at Stratford. To contribute, contact the CLH at 703-228-5966 or localhistory@arlingtonva.us.

This digital access project was completed using new FY2017 funding in the Department of Libraries budget dedicated to increasing public access to government records and archival materials.

The Center for Local History at Arlington Public Library is committed to collecting, preserving, and sharing the history of Arlington County.

Their unsolicited

Their unsolicited