Join us for a series of stories from the Center for Local History highlighting members of our community who made a difference in ways that helped shape our history and created positive change.

Their voices were not always loud, but what they said or did had a significant impact on our community.

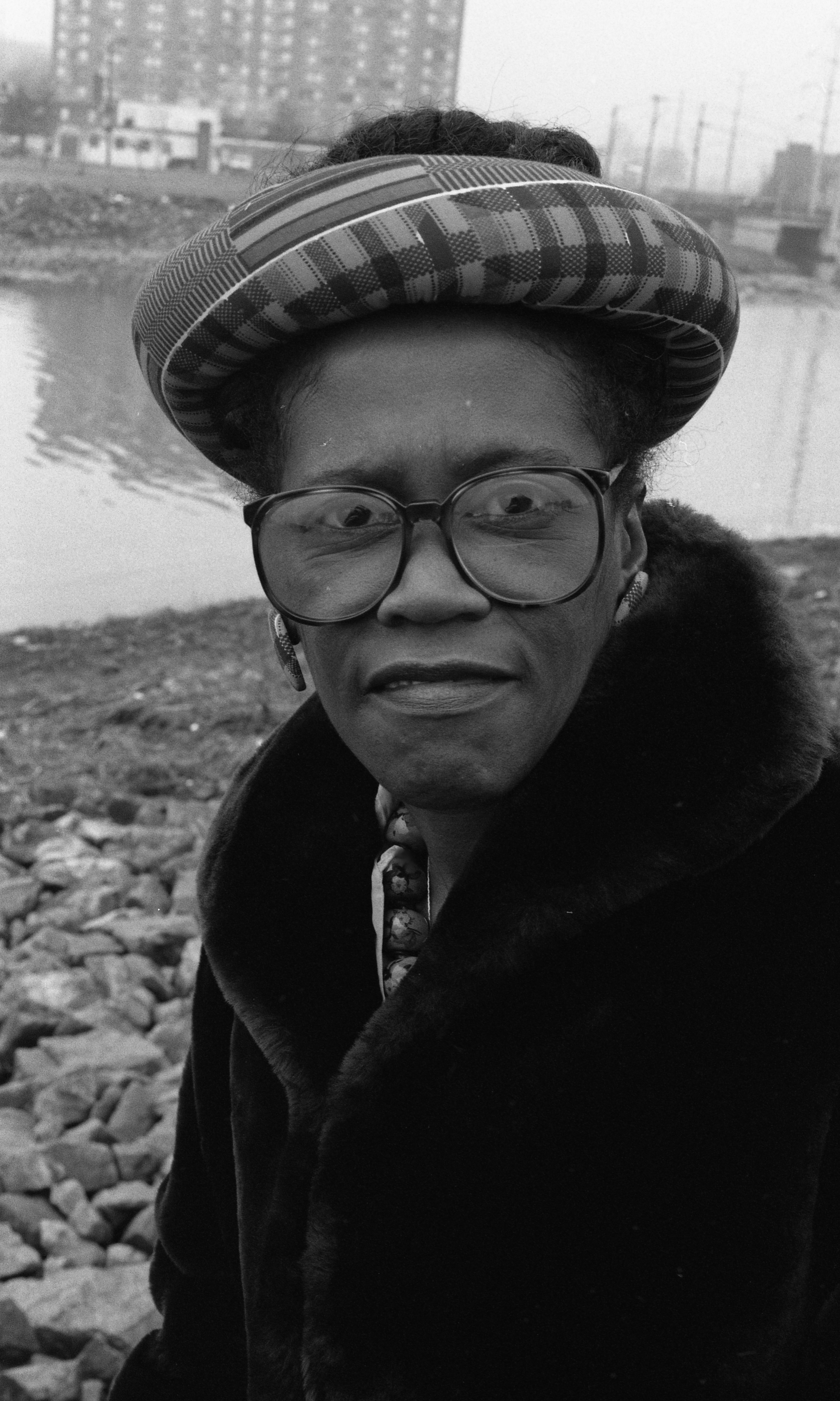

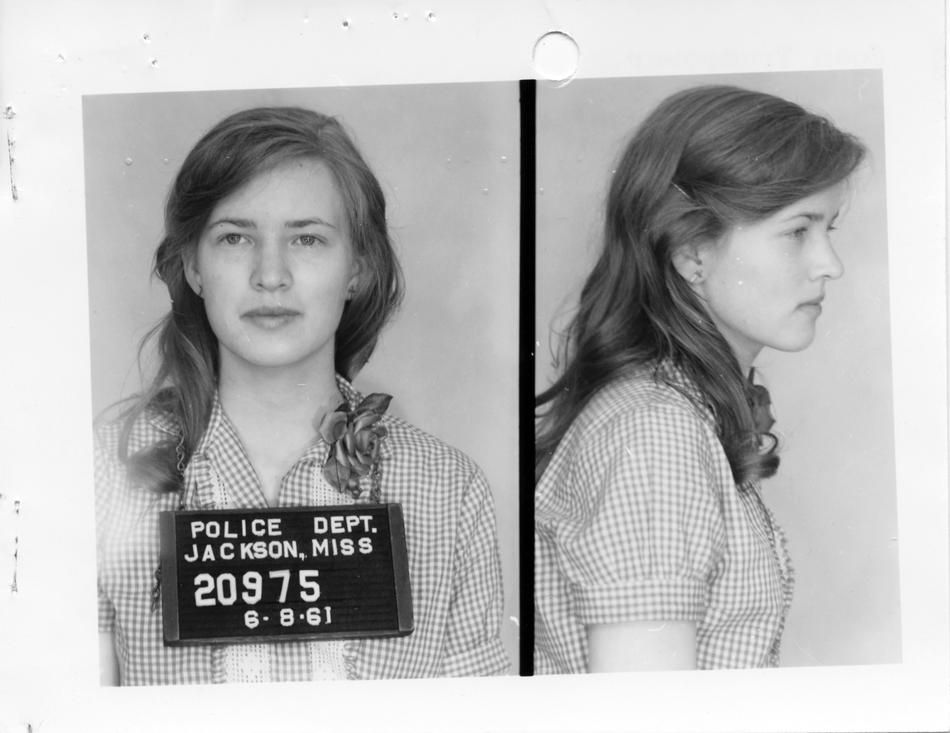

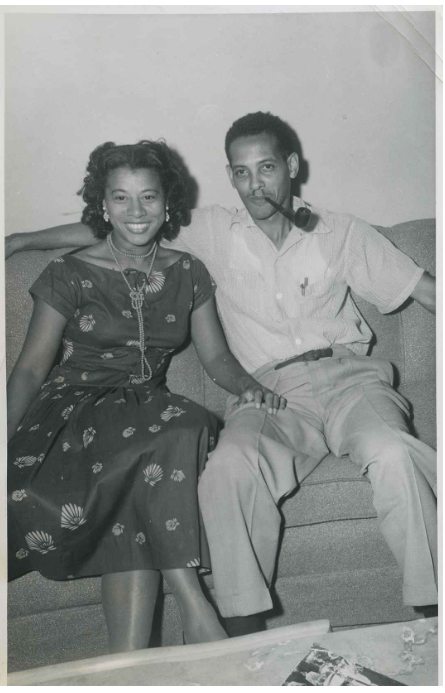

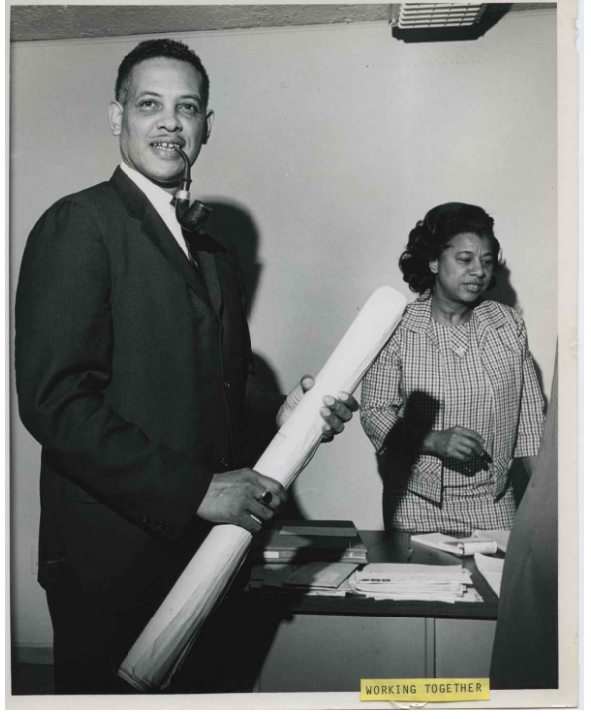

Joan Cooper

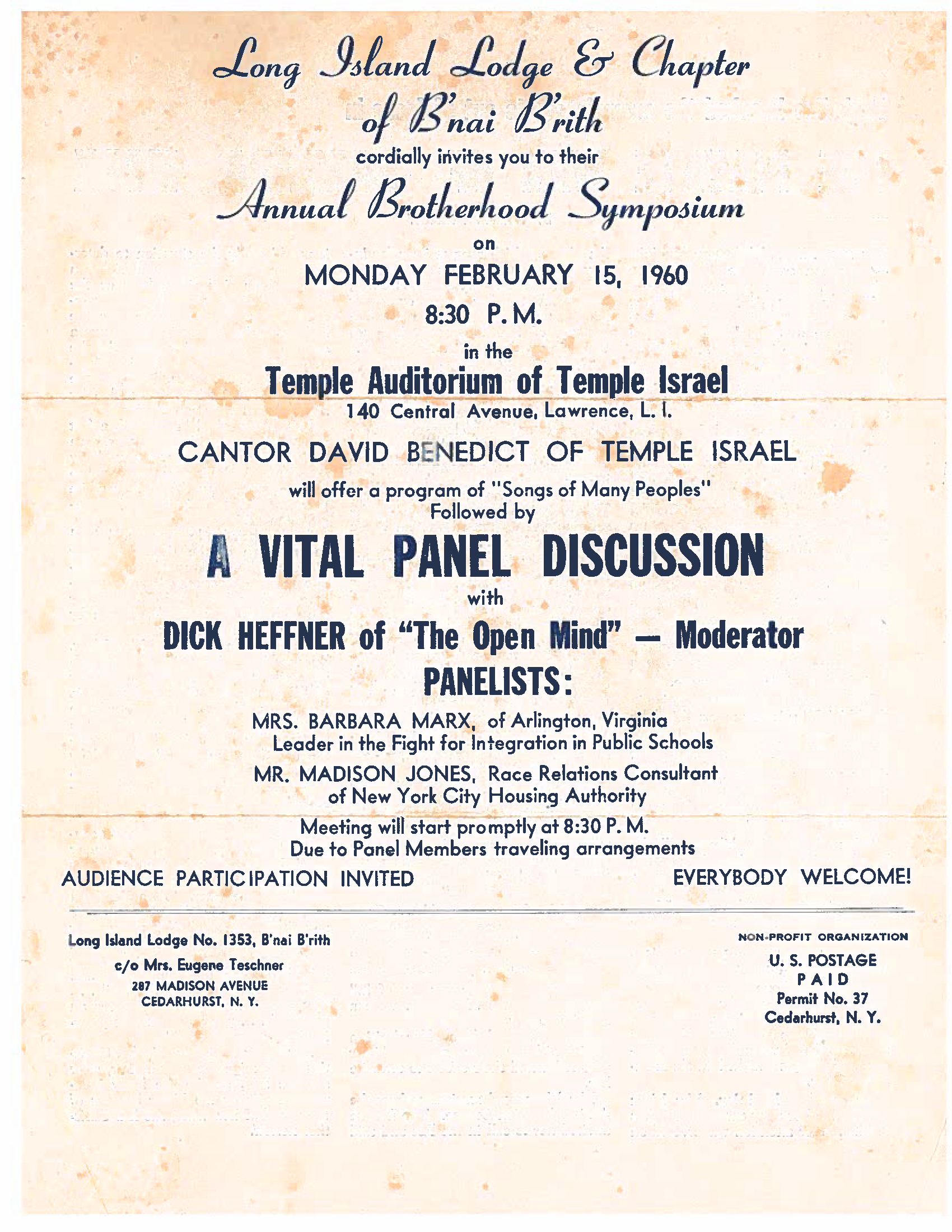

Joan Cooper (1940-2014) was an Arlington social and civic activist, community leader, and passionate anti-drug campaigner. Born and raised in Arlington’s Green Valley/(Nauck) community, Cooper first became an activist in the 1960s as a member of the Action Coordinating Committee to End Segregation in the Suburbs (ACCESS). In July 1966, ACCESS participated in sit-ins and pickets demanding that fair and equal housing opportunities be made available to all apartment renters in Arlington County.

Shifting her focus to her immediate community, Cooper tackled issues of drug abuse, crime, and poverty/unemployment, worked to help drive out drug dealers, sought to increase and provide treatment and counseling for addicts, and endeavored to find positive alternatives and activities for young people.

She challenged her community to make changes as well, stating, “People have to realize, that we as community members have to do our job, too.”

In 1970 Cooper led a series of marches and held informal “rap sessions” in Green Valley, focusing on the dangers and extent of drug abuse in the community. She also founded an antidrug facility called the Community Inn, which functioned as a counseling and treatment referral center.

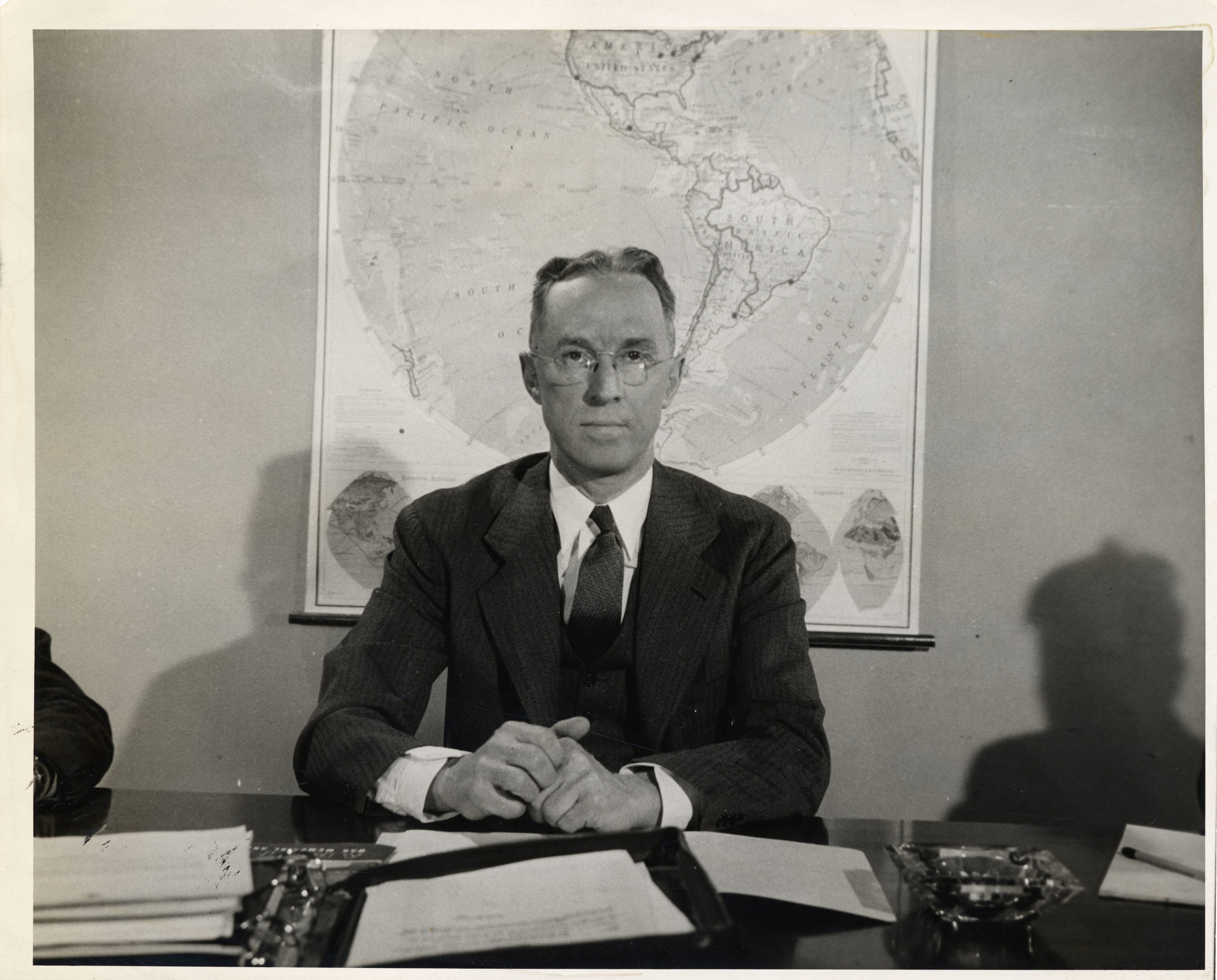

With her message of “Be persistent, consistent, and insistent,” Cooper helped launch an initiative called “Crackdown on Drugs” in July of 1992. Cooper’s dedication and leadership in this campaign were hailed by then-President George H.W. Bush upon his visit to Drew Model School. Her efforts included driving individuals to drug and alcohol detox programs, helping to patrol corner blocks of the Green Valley neighborhood, and serving as a liaison between residents and police.

In response to what Cooper and others in Green Valley felt was often an inadequate police presence in the area, the Community-Based, Problem-Oriented Police (CB-POP) unit was established at 2430 S. Kenmore St. in March 1992 because of her advocacy.

In that same year, she was named a Notable Woman of Arlington by the County’s Commission on the Status of Women. The Arlington Community Foundation continues to maintain a fund in Cooper’s name which supports a variety of endeavors, including student scholarships, sports programs at local schools, and repair efforts for Lomax A.M.E. Zion Church.

In 1993, Cooper was the first recipient of the William Newman Jr. Spirit of Community Award, given by the Arlington Community Foundation. She also received a William Brittain Jr. Community Appreciation Award from the Arlington branch of the NAACP. In addition, she was a member of the United Way of the National Capital Area and remained an active presence in her community until her passing in 2014.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields