September 1861 - August 1863

While the first successful hot air balloon flights were completed in France in the 1790s, due to the work of Thaddeus S.C. Lowe (1832-1913), Arlington is home to their first use by the United States military. Lowe was a scientist and inventor who would go on to be known as the “Grandfather of Military Aerial Recon in the United States.”

Professor Lowe, c. 1860, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

Professor Lowe, 1861, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

By the 1850s, Lowe was well regarded for his advanced meteorological theories and his reputation as an amateur balloonist. He gained national attention in 1861 when, on a test flight for a Trans-Atlantic balloon voyage, he was blown off course and imprisoned in South Carolina as a Union Spy.

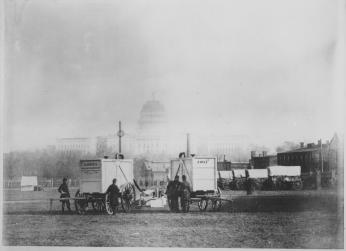

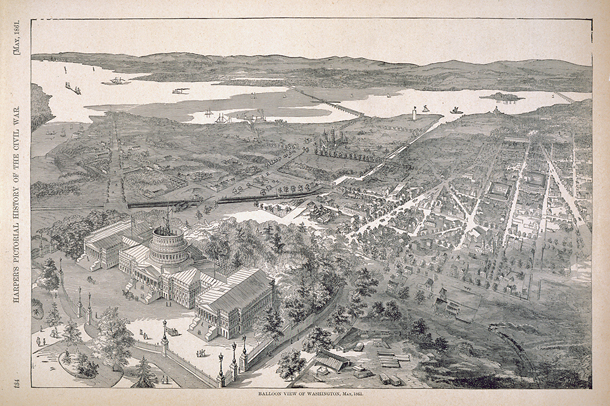

Shortly after being cleared as a scientist, Lowe was released from jail and invited to Washington D.C. to perform demonstrations of his balloons for President Abraham Lincoln. On July 11, 1861, by hanging telegraph wires to his staff on the ground, Lowe sent a message from 500 feet above the White House that read,

“This point of observation commands an area near 50 miles in diameter. The city with its girdle of encampments presents a superb scene. I have pleasure in sending you this first dispatch ever telegraphed from an aerial station.”

President Lincoln was so impressed with Lowe and his balloons that he offered him the civilian position of Chief Aeronaut of the newly formed Union Army Balloon Corp.

Lowe’s Balloon Being Prepared in front of the Capitol Building, 1861, Photo Courtesy of Ghosts of D.C.

Balloon View of Washington, May 1861, Photo Courtesy of U.S. Senate

Formation of Balloon Corps (Summer 1861)

Stationed at Fort Corcoran, in today’s Rosslyn/North Highlands Neighborhoods, the Balloon Corp’s mission was to provide aerial reconnaissance of Confederate troops just outside of Arlington.

The Balloon Corp was expanded after the first Battle of Bull Run. Lowe’s fleet of Balloons would grow to seven balloons that could be stationed up and down the Potomac River. To transport their balloons, the Balloon Corp was given use of a coal barge converted to be the world’s first aircraft carrier, the USS George Washington Parke Custis.

During the summer of 1861, Lowe and the Balloon Corp would make multiple ascensions over the Arlington Heights and Balls Crossroads (now Ballston) area in order to observe Confederate positions at Falls Church.

Drawing of USS George Washington Parke Custis with balloon ascending over Potomac River near Mount Vernon, November 1861, Photo Courtesy of United States Naval Institute

Lowe’s balloons were perfect for defensive observations, as he could safely evaluate the Confederate’s position and strength from the relative safety of his balloon. By using signal flags and a telegraph in the balloon, Lowe was able to relay messages quickly to the forces on the ground.

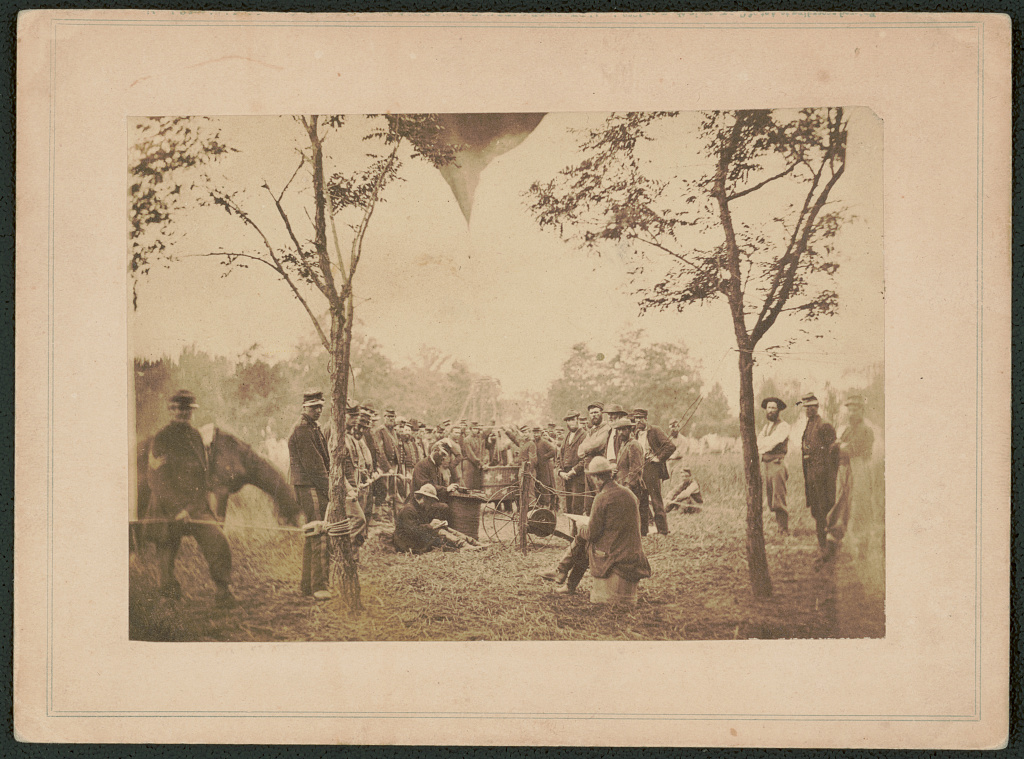

Lowe filling balloon from portable hydrogen generator, Gaines Mill Virginia, June 1, 1862, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

The U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission reported,

"On September 24, 1861, Lowe ascended to more than 1,000 feet (305 meters) near Arlington, Virginia, across the Potomac River from Washington, DC, and began telegraphing intelligence on the Confederate troops located at Falls Church, Virginia, more than three miles (4.8 kilometers) away. Union guns were aimed and fired accurately at the Confederate troops without actually being able to see them—a first in the history of warfare."

Although the Confederate troops were unable to see the Union guns firing at them, they were often able to see the reconnaissance balloon. Enemy soldiers and artillery frequently fired potshots at Lowe, often hitting near his staff on the ground below him. This earned him the nickname of "The Most Shot at Man" of the Civil War by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum.

Distrust of the Balloon Corp

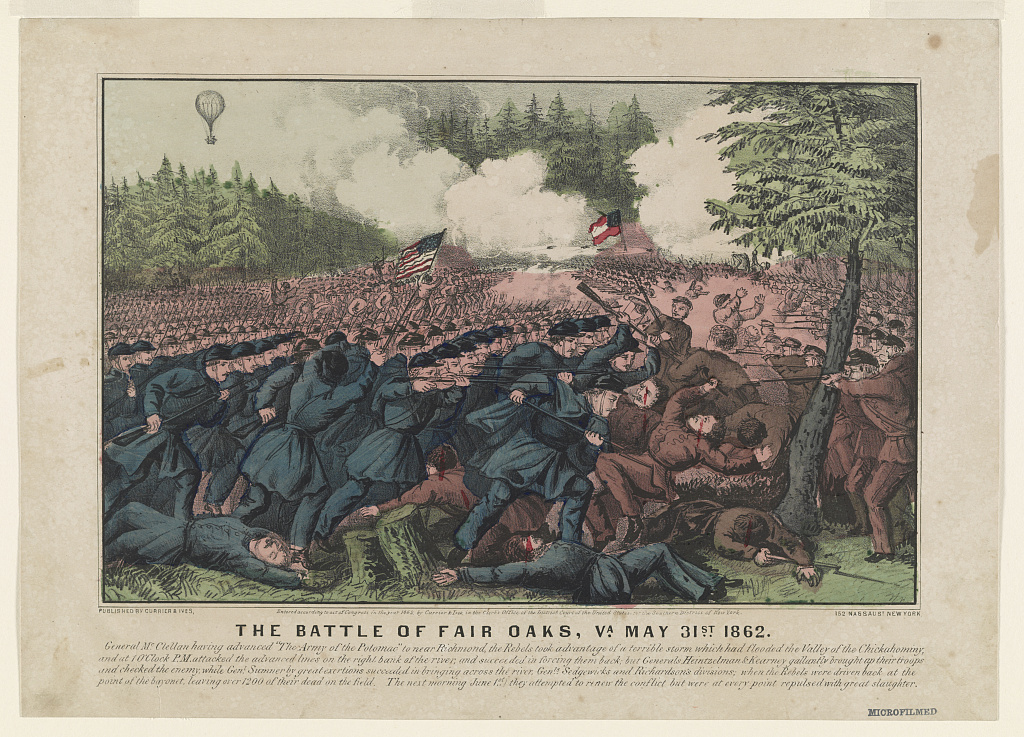

Over the next two years, Lowe and the Balloon Corp would provide reconnaissance for the battles of Yorktown, Seven Pines (Fair Oaks), Fredericksburg, Mechanicsville, and Chancellorsville. But Lowe’s information was often ignored by his commanding officers, and many were reluctant to trust a civilian employee of the Army.

The Battle of Fair Oaks, VA, May 31, 1862, “Intrepid” War Balloon in Distance, Photo Courtesy of National Park Service

Although Lowe reported that he was able to accurately call out Confederate positions in good weather, some Union Army members believed the reports were altered to "render their own importance greater, thereby insuring themselves what might be profitable employment." As a result, many Union generals distrusted the Balloon Corp’s information, instead favoring traditional methods of reconnaissance. George Armstrong Custer, who rode in Lowe’s balloons in April 1862, stated:

“The large majority of the army, without giving it a personal test, condemned and ridiculed the system of balloon reconnaissance”

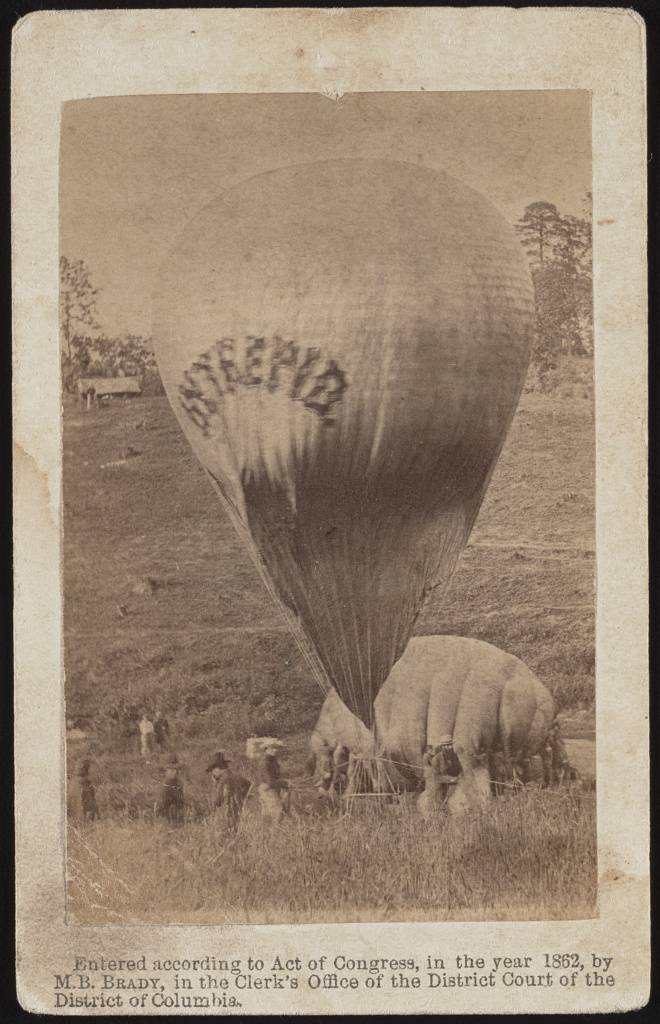

Lowe filling balloon INTREPID from balloon CONSTITUTION at Fair Oaks, VA, 1862, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

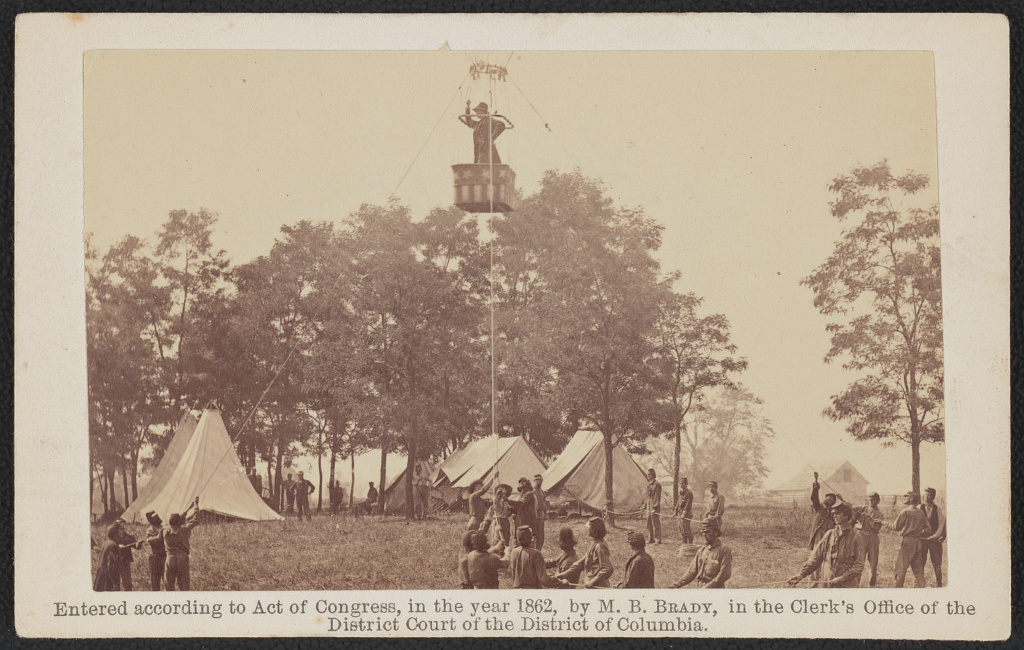

Balloon Camp, Gaines' Hill, near Richmond, VA: telegraphing, reporting, and sketching during the Battle of Fair Oaks, June 1, 1862, Photo Courtesy of Library of Congress

End of the Balloon Corp

The Balloon Corp would not last to the end of the Civil War. In 1863, Lowe resigned after a dispute about his pay. Shortly after, the unit was rejected from joining Col. Albert Myer’s Signal School and then disbanded.

Lowe retired to Pasadena, California, where he later won the Elliott Cresson Medal for the Invention Held to be Most Useful to Mankind for his work in the cold storage industry. He also founded the Mount Lowe Railway and the Citizens Bank of Los Angeles, which is now a part of Wells Fargo. His granddaughter, Florence Lowe “Pancho” Barnes, was a pioneer aviator who broke Amelia Earheart’s air speed record in 1930.

Help Build Arlington's Community History

The Center for Local History (CLH) collects, preserves, and shares resources that illustrate Arlington County’s history, diversity and communities. Learn how you can play an active role in documenting Arlington's history by donating physical and/or digital materials for the Center for Local History’s permanent collection.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields