To mark the passing of the hero of the American Space Age, we’re re-sharing our blog post from Feb. 14, 2012, written on the 50th anniversary of his first space trip to orbit the earth.

Glenn’s death at age 95 was announced Dec. 8, 2016.

Fifty years ago this month, on Feb. 20, 1962, John Glenn became the first Arlingtonian to orbit the Earth.

While often celebrated for an Ohio pedigree on par with the Wright brothers of Dayton, New Concord’s favorite son was also among the wave of transients to settle in suburban Washington amid the Cold War-era build-up of jobs and conveniences.

A Marine test pilot, and veteran of both World War II and the Korean War, Glenn was commuting almost four hours a day between Maryland’s Patuxent Naval Air Station and a desk assignment in temporary offices on the National Mall.

He and his wife, Annie, and their two children were lured to Northern Virginia in 1958 by the promise of a good school district and “a beautiful tree-shaded hillside.”

Arlington real estate prices were already “high” for the times, Glenn later recalled in his autobiography, but not completely beyond reach of a junior officer’s annual income, roughly $10,000.

In fact, another Marine family joined the Glenns in building next-door ranch homes on quiet North Harrison Street.

They were not alone: The county grew by almost 30,000 residents that decade, having more than doubled in population the previous ten years.

For John Glenn, already in his late 30s, and his wife, Annie, Arlington was a particularly idyllic pause in the series of moves typical of military families.

Their son, David, and, soon, his sister, Lyn, simply had to cross the street to get to class at Williamsburg Junior High School. Their father had only to point his used Studebaker across Chain Bridge or Memorial Bridge to be at work within minutes.

In the eyes of his new neighbors, Glenn was already on the road to modest TV-age celebrity, having recently set a transcontinental-flight speed record, followed by an appearance on “Name That Tune.”

When the newly formed NASA launched its search for the men to beat the Soviets into space, Glenn’s curiosity, patriotism and media savvy were a natural fit. Despite the obvious domestic sacrifices to come, he and Annie celebrated the news of his selection (and their 16th wedding anniversary) with dinner at McLean’s Evans Farm Inn.

* * *

Astronaut headquarters and training were set for NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, 180 miles of pre-I-95 driving from Arlington County. The other six men set to fly Project Mercury would have their families near the job but the Glenns weren’t ready to leave Northern Virginia after less than a year.

So they decided to remain in the new house with the bucolic backyard, while the astronaut-in-training went back to a long commute, this time returning home only on weekends.

His other quarters were those for Langley bachelors or hotel rooms near NASA business across the country. The Studebaker was replaced by a bookish new NSU Prinz that got 45 to 50 miles to the gallon–and the scorn of Glenn’s hot-rod-driving colleagues.

His other quarters were those for Langley bachelors or hotel rooms near NASA business across the country. The Studebaker was replaced by a bookish new NSU Prinz that got 45 to 50 miles to the gallon–and the scorn of Glenn’s hot-rod-driving colleagues.

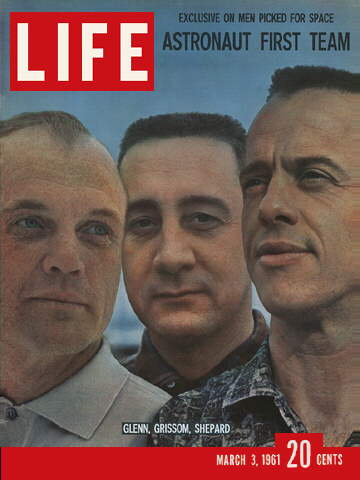

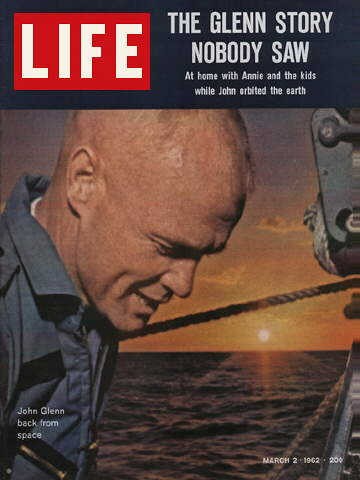

The expense of keeping the family in Arlington was no longer a concern, thanks to income from an exclusive contract with Life magazine. Each astronaut would get close to $70,000 for his story over the three years of the program. They would become household names long before blastoff.

But by the time Alan Shepard and Gus Grissom flew their arch-shaped, suborbital flights in 1961, the Mercury 7 program had become the story of also-rans. Yuri Gagarin and the Soviets made it to space and orbit first and the differences between the two programs weighed heavy on Americans.

NASA’s two flights each lasted roughly 15 minutes, while the second cosmonaut up, Gherman Titov, orbited Earth almost 18 times during an August 1961 mission that lasted more than a full day. A radio specialist in Arlington, Sgt. James Duffy, picked up Titov sending greetings to the American people in Russian.

The Glenn mission was set initially for December 1961 but weather and technical issues forced almost a dozen no-gos. The new Mercury-Atlas rocket remained on the pad at Cape Canaveral.

All the while, Annie Glenn and her children kept vigils by the television at North Harrison Street, as reporters and other rubberneckers waited outside. Newspapers readily printed the address.

After one five-hour countdown to frustration in January 1962, Vice President Lyndon Johnson was left to fume in his limousine down the street when Mrs. Glenn refused to open her home to a photo-op on a far larger scale than Life ever wanted.

Not only did Glenn burn up the telephone lines to Washington and Arlington in support of his wife’s decision, but he dared his superiors on threats to bump him from the mission.

Finally, Feb. 20, 1962 happened.

When John Glenn brought his Friendship 7 back to Earth after a sometimes harrowing five-hour flight of three orbits, he was America’s favorite son, the new Lindbergh. NASA had at last proven its capabilities for the world to see, especially the Soviets.

Despite the ensuing hoopla and hero’s travels, home for Glenn remained in Arlington. There were now distinct advantages for the space program’s best salesman to be a few minutes from the nation’s capital, whether it meant having a closer relationship with President Kennedy and his family, or being asked by a desperate State Department to host a last-minute goodwill barbecue for Gherman Titov.

At one point during the rainy cookout, the astronaut and cosmonaut sweated side-by-side in Glenn’s carport, trying to keep the charcoal under control.

Even Lyndon Johnson was welcomed at the house for Glenn’s 41st birthday party, staying well into the night.

But the push toward the moon and a new Manned Spaceflight Center near Houston meant a commute even beyond John Glenn’s endurance level. The family packed up for Texas in 1963, heading for a new community customized to the needs of celebrity space travelers.

Ultimately considered too valuable for a second space race launch, Glenn would have to wait for the shuttle

era to return to orbit. But his unmatched people skills eventually returned him to the Washington area for a quarter-century as U.S. senator.

John Glenn remains a part-time resident of the metropolitan D.C. area to this day and still visits his first spacecraft at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum.

I remember oh so well, the homecoming we as local residents gave John and Annie. I was among the 15-20 Junior High School students perched atop an adjoining car port roof sharing our excitement “all the way USA!” and just plain “welcome home!”

Our little group even got a 5 second claim to fame by having our “roof top” welcome shown on the (if I remember the TV show name correctly)The Today Show.

Even at my age,and for me, the spirit of Space and flight still lives on!

Sorry Virginians – five years residency in Arlington does not make John Glenn the first Arlingtonian in orbit. John Glenn is an OHIOAN! After his NASA career, he returned to his home state and served it as an OHIO Senator for a quarter of a century. PS Neil Armstrong is also an Ohio boy. Buckeye proud!