A new bridge to Arlington’s past

On Sept. 10, 2015, Arlington officials will formally dedicate “Freedmans Village Bridge,” the replacement overpass for Washington Boulevard at Columbia Pike.

On Sept. 10, 2015, Arlington officials will formally dedicate “Freedmans Village Bridge,” the replacement overpass for Washington Boulevard at Columbia Pike.

The naming honor for the 19th century Arlington community of former slaves was approved by the state after a 2008 request from the County Board. Washington Boulevard is officially a state route.

The new bridge incorporates medallion images of the village, which was established as a model community by federal military officials on the captured property of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Custis-Lee estate in 1863. The village, which included housing, schools, a hospital and vocational facilities, was intended to be a temporary stopping point for the former slaves to establish themselves before moving on. Yet the community lasted and even thrived until 1900 when, after decades of trying, the government closed the village, persuading residents to accept payment to leave. Many found homes in other Arlington neighborhoods such as Hall’s Hill and Nauck.

Arlington TV spoke with Dr. Talmadge Williams in 2009 to explore the history and legacy of Freedman’s Village. Williams, an Arlington historian, educator and civil rights leader, died last year.

Although “Freedman’s Village” is now commonly spelled with the apostrophe, County preservation staff recommended that the bridge name not include the punctuation as a more accurate rendition of the name from when the community existed.

More than 28,000 residents of Freedman’s Village are buried in Section 27 of Arlington National Cemetery.

Thanks for sharing the black history of Arlington,Virginia. We need more information like this.

And to think only twenty-five years ago, I asked about information about the Freedmans Village when my ex-husband and I visited Arlington Cemetery, and no one seemed to know anything about it. My ex-husband’s great great grandfather served at the Abbott Hospital as a steward, and lived on the grounds behind the mansion. We were looking for any information, and we didn’t get any that day.

Just thought you would appreciate this.

How many of us were taught this in American or Black History? The real question, are our children being taught items like this today?

Arlington Cemetery was once site of a thriving black town

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

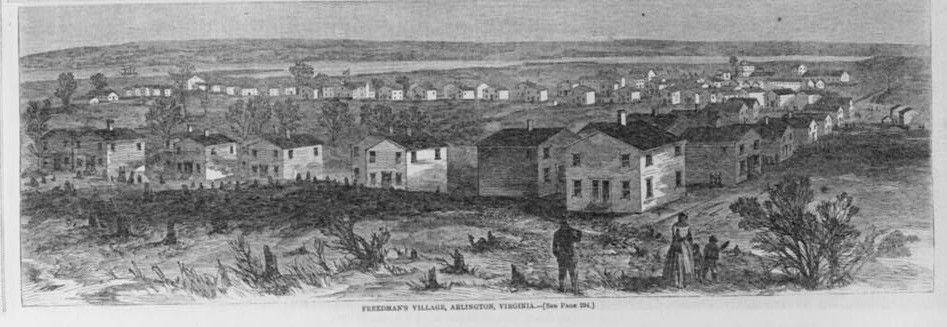

A group of freedmen are pictured in “Freedman’s Village,“ the black community built on land confiscated from Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

THE ASSOCIATED PRESS

Published: April 25, 2010

ARLINGTON Charter buses roll up to Arlington National Cemetery every day, depositing tourists who scramble uphill to see the eternal flame on President John F Kennedy’s grave. People stream in all directions, toward the Tomb of the Unknowns or to remember at tombstones of loved ones lost to war.

Few, however, head downhill to a quiet corner near the Iwo Jima Memorial.

Down here, there are no memorials to ancient battles, no ornate headstones honoring long-dead dignitaries. There are only rows of small unassuming white tombstones, many engraved with names like George, Toby and Rose.

They are the only visible reminders that part of the nation’s most storied burial ground sits atop what used to be a thriving black town — “Freedman’s Village,” built on land confiscated from Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee.

Milton Rowe recently made his way slowly around the famous grounds with Wayne Parks. There’s nothing here now to tell visitors that freed slaves once lived here, but the two men say they feel a connection with this land because they can both trace their ancestors to Freedman’s Village.

Parks said he remembers his grandfather repeatedly bringing him to the cemetery as a child to explain the bond. Parks’ great-grandfather, James Parks, lived in Freedman’s Village and other locations around the cemetery after being freed from servitude to the Lee family.

“I was sitting on this wall gazing out over the cemetery, and all of a sudden, I got it,” Parks said. “Our DNA is intrinsically intertwined in this property, integrated in this property. The spirits of my ancestors continue to exist here in this property, so I find like my grandfather, I now come here for strength, I come here to commune with them.”

Arlington National Cemetery was established on land confiscated from Lee and his family in 1861 after the general took command of the Confederate forces.

The Civil War leaders of the Union buried soldiers’ bodies on the property in hopes that Lee would never want to return, and Parks’ ancestor dug the very first grave near the Freedman’s Village burial site.

The federal government turned some land about a half-mile north of Lee’s mansion into a town specifically for freed slaves who had nowhere to go. At its height, more than 1,100 former slaves lived in a collection of 50 1½-story duplexes surrounding a central pond.

Although the town was supposed to be temporary, the freed slaves put up churches, stores, a hospital, mess hall, a school, an “old people’s home” and a laundry — to make a life for themselves.

“I think it would have very much resembled a town anywhere in America today with that population. They had the same needs as anywhere, and they sustained themselves by working,” said Thomas Sherlock, historian at Arlington National Cemetery .

Eventually, the village site, with a spectacular view of the nation’s capital and the Potomac River , became desirable for development. Despite impassioned protests from the freed slaves, the federal government paid the residents $75,000 for the buildings and property, and tore down the town in 1900.

Saving the city would have been a “gift to the American people to remember the struggles which seem like was a long time ago, but 150 years is not that long ago,” Sherlock said.

The only trace of Freedman’s Village left on the grounds are the lonely graves in Section 27 near the Iwo Jima Memorial.

One Lord, One faith, One baptism

Ephesians 4:5