Each January, the world remembers Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Best known for his efforts to eradicate racism and segregation, and for his philosophy of nonviolence, Dr. King's leadership of the Montgomery bus boycott led to "court cases around the nation that challenged and overturned the constitutionality of Jim Crow laws."

One of those places was Arlington - the first county in Virginia to desegregate public schools. This story is documented in Project DAPS, a database of archival materials related to the legal and moral battles that culminated on February 2, 1959. The Project DAPS database is culled from the Center for Local History's Community Archives and includes thousands of photos, documents, and recordings.

The following article was written by Center for Local History researchers and relies on many primary source documents held in the Project DAPS collection. A note to readers on some of the language used in the Project DAPS database and this article.

The Story of Segregation and Desegregation in Arlington

At 8:45 a.m. on February 2, 1959, four young students from the nearby Hall’s Hill neighborhood entered Stratford Junior High School in Arlington, Virginia.

Ronald Deskins, Michael Jones, Lance Newman, and Gloria Thompson walked into Stratford Junior High School on February 2, 1959.

When they stepped into Stratford that day, they became the first students to desegregate a public school in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Many Arlingtonians know that theirs was the first county in Virginia to desegregate. It is a point of pride. But it’s not the whole story.

It is a story that is sometimes difficult. One that offers few easy answers. It’s a story about how “desegregation” doesn’t necessarily mean the same thing as “integration.” It’s the story of how a coalition of primarily Black activists and white moderates spurred progress, sometimes haltingly, and often with great difficulty.

These two groups were not always in agreement, but together they were able—gradually, over several decades—to turn the tide of race relations in Arlington, reversing the oppressive rule of Jim Crow.

Education Under Jim Crow

Arlington, like all of Virginia—and the entire South—was a segregated society in the first half of the 20th century. A complex set of laws governed race relations, limiting the access of Black citizens to a variety of social services and businesses.

Together these laws were known as “Jim Crow” laws, a term that can be traced to a song popularized by the blackface entertainer Thomas D. Rice in the 1830s. After the end of Reconstruction, when Federal enforcement of racial equality ended in the South, Southern states began to establish new laws to keep the races separate.

Jim Crow in Arlington

"The New Virginia Law to Preserve Racial Integrity," from Virginia Health Bulletin, vol. XVI, March 1924, Extra No. 2

In Virginia, Jim Crow took many forms. It was even enshrined in the new Constitution of the Commonwealth of Virginia, established in 1902. The new constitution disenfranchised many Black citizens by means of voting restrictions. In the section describing public schools, it stipulated that “White and colored children shall not be taught in the same school.”

Another important law was the Racial Integrity Act of 1924. This act was specifically designed to prohibit miscegenation, or “race-mixing.” It defined “whites” as only those people "who [have] no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian." To preserve whiteness, the act prevented marriage between whites and nonwhites, who were described in the law as “colored.” It required that every birth certificate issued in the Commonwealth state the race of each infant. It also required the forced sterilization of Virginia citizens found to be “mentally ill” or “mentally deficient.”

In addition to the Virginia Constitution and state laws like the Racial Integrity Act, Jim Crow took the form of numerous local ordinances as well as property covenants that prohibited selling homes in certain neighborhoods to “colored” citizens.

Black Public Education in Arlington County Before 1947

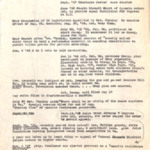

Public Education for Negroes in Arlington County, Virginia, from 1870 to 1950, Dissertation by Ophelia Braden Taylor, June 1951.

Prior to the Civil War, it had been illegal for Blacks to gather together for purposes of education, whether they were free or enslaved. For that matter, there had not been a system of public schools for white students either. Virginia had historically been opposed to public schools, as had most of the South. Private schools served the Commonwealth’s population of white elites.

After the Civil War, however, Virginia began to establish public schools. In 1870, Arlington County (then known as Alexandria County) established three public schools: the whites-only Columbia and Walker schools and the Arlington School for Negroes in Freedman’s Village, a settlement of freed former slaves on the federally seized grounds of Robert E. Lee’s Arlington plantation.

The history of Black public education in Arlington between 1870 and 1950 is told eloquently and in great depth in Ophelia Braden Taylor’s 1951 Public Education for Negroes in Arlington County, Virginia from 1870 to 1950, which she completed while working on a Master of Arts in Education at Howard University.

This document came to the Arlington Public Library’s Center for Local History as part of the papers of George Melvin Richardson, former principal of Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High School. It is an invaluable and thoroughly researched document that is almost certainly still the best history of the topic to date.

NAACP Advocacy for Better Schools

Until 1932, public education for people of color in Arlington was limited to primary school. Hoffman-Boston Junior High School (later Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High School) opened that year, allowing Black Arlingtonians to pursue secondary school within the county.

However, Hoffman-Boston was not accredited by the state until the 1950s, and its facilities were not up to the standards of the county’s whites-only schools. Many Black students still commuted to Washington, D.C. to get a secondary education.

As early as 1941, the Arlington chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) brought pressure to bear on the county School Board for better facilities. And in 1947, the NAACP brought a suit against Arlington County Public Schools, asserting that the education provided to Black students was not up to the standards of the white schools. The suit would lead to new investment in the county’s Black schools.

1941: Esther Cooper’s Campaign for Better Schools

Letter to Jackson Ross of the Arlington County School Board from Filmore Peyton, President, and Esther Cooper, Secretary, of the Butler-Holmes Citizens Association, dated March 18, 1947. The letter asks for additional funds from a county bond issue to finance the building of a new Hoffman-Boston High School and improvements to Kemper and Langston elementary schools.

Thirteen high school seniors graduated from Hoffman-Boston in 1941, the school’s first graduating class. In the seven years since these students had advanced to junior high, neither the junior high nor the high school had received accreditation from the state. The facilities in the former elementary school were limited, and teachers often had to teach multiple subjects. While the teachers at Hoffman-Boston were considered to be excellent educators, the school’s small faculty simply couldn’t offer the same variety of courses that the larger all-white Washington-Lee High School could.

Nearly three-quarters of Black students in Arlington who were of age to attend junior or senior high school were either attending schools in Washington D.C. or were not attending school at all.

Esther Cooper, president of the Arlington chapter of the NAACP, believed the School Board could and should do better. Cooper began to contact parents in the school district, urging them to pressure the School Board for changes. The Butler-Holmes Citizens’ Association soon joined the NAACP in pressuring the School Board for these reforms.

Throughout the decade, Cooper continually advocated for several improvements: separate buildings for the junior and senior high school programs; better facilities and more teachers to allow for a fuller curriculum; and accreditation for both the junior and senior high school programs.

In this 1947 letter from the Butler-Holmes Citizens’ Association, signed by Esther Cooper, we see these demands reiterated six years after her campaign initially began.

1950: Constance Carter v. School Board of Arlington County

Narrative detailing activities of members of the Arlington Branch, NAACP, and other concerned citizens to compare white and African-American schools in Arlington and their legal actions regarding school equality.

In 1946, the District of Columbia school system announced that students from Arlington who attended D.C. schools would have to pay tuition. This presented a special difficulty to Arlington’s Black community. Black public schools in Arlington did not have the same resources as those of the county’s white schools or schools in the District. Moreover, the tuition represented a larger burden for most Black Arlingtonians, who made less on average than the county’s white citizens.

Urged on by the NAACP, the Arlington School Board agreed to pay tuition for the remainder of the year for Arlington students enrolled in D.C. schools. During the next few months, however, there were few signs that progress was being made toward improved facilities or offering more classes for Black students in the county.

On the opening day of the next school year, September 3, 1947, Constance Carter, a Black high school student in Arlington, arrived at the all-white Washington-Lee High School. Her mother, NAACP member Eleanor Taylor, accompanied her. Together they attempted to enroll Constance at the school, stating that Hoffman-Boston did not offer the classes she wished to take, including Spanish, typewriting, and physical education.

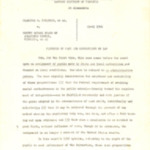

Civil Action No. 331 in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Columbia, Alexandria Division.

Washington-Lee principal Claude Richmond refused Carter’s request, citing the Commonwealth’s requirement that all public education be segregated. Carter and Taylor, represented by NAACP attorneys Spottswood W. Robinson III and Martin A. Martin, then filed a lawsuit against the county schools.

Constance Carter v. The School Board of Arlington County, Virginia: Complaint and opinion, 1950. This is the May 31, 1950 opinion of Martin A. Soper, delivered May 31, 1950, overturning Albert Bryan's dismissal of Carter's 14th Amendment case.

Robinson and Martin saw this as a Fourteenth Amendment “equal protection” case. Although Supreme Court case Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) held that equal protection and equal rights are not abridged as long as public facilities and services are “separate but equal,” public education for Blacks in Arlington was demonstrably unequal. While the presiding District Judge Albert V. Bryan acknowledged the inequality of facilities and classes offered, he did not accept that this resulted from an intentional disparity. He ruled instead that it was a result of “defects of administration for administrative correction, not constitutional offenses for judicial interference."

Upon appeal, however, federal judge Martin A. Soper reversed the decision, ruling for Carter on May 31, 1950. He then ordered Judge Bryan to notify the School Board that they would be required to provide equal facilities for the county’s Black students.

In the next few years, the pay rate for Black teachers in Arlington was raised to meet that of white teachers, and money was earmarked for improvements to the facilities of Hoffman-Boston and other Black schools.

1954: Arlington in the Wake of Brown v. Board of Education

On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled on Brown v. Board of Education. In a unanimous decision, the court reversed the case law of Plessy v. Ferguson. Chief Justice Earl Warren, writing for the high court, held: “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.”

Brown v. Board of Education sent shockwaves throughout the South, including Virginia. For some, especially in the Black community, it was hailed as a great victory. For others, largely white, it was seen as a threat to their very way of life.

In the capital of Richmond, U.S. Senator Harry Flood Byrd and his tightly controlled political machine began to gear up a program known as “Massive Resistance,” intended to defy the Supreme Court ruling by any means necessary, including shutting down the schools if need be. The state removed Arlington’s democratically elected School Board and installed a new board more sympathetic to the segregationist cause.

But there was another group at play in Arlington, one that proved instrumental in the story of desegregation: white racial moderates, who may not have minded segregation but didn’t want to lose their school system over it. In the end, they were pivotal in advancing the cause of desegregation over the objections of much of the appointed School Board.

1955: Massive Resistance

A copy of the Gray Commission report ("Public Education Report of the Commission to the Governor of Virginia"), with notes handwritten on the front page regarding price-fixing and raising teacher salaries.

On the day of the Brown decision, Senator Harry F. Byrd issued a statement saying that the ruling would “bring implications and dangers of the greatest consequence. It is the most serious blow that has yet been struck against the rights of the states in a matter vitally affecting their authority and welfare.”

In 1955, the state released the Gray Commission Report on Public Education. The report was created by a group of politicians, lawyers, and academics from around the state selected by segregationist Governor Thomas B. Stanley. The commission advised getting rid of state laws requiring mandatory school attendance. No child should be required to attend an integrated school, they argued, against their parents’ wishes. Rather, the “parents of those children who object to integrated schools, or who live in communities wherein no public schools are operated, [should] be given tuition grants for educational purposes.” (Emphasis added.)

The Gray Report, in other words, recommended offering a back door, so that schools could be shut down rather than be forced to integrate. This policy was adopted, and the next year Governor Thomas Stanley pushed through a legislative agenda that included a law allowing the allocation of public school money for tuition grants to students attending segregation academies.

Address of Governor Thos. B. Stanley to the General Assembly submitting a bill for a referendum on holding a Constitutional Convention to amend Section 141 of the Constitution of Virginia. 4 pages

The blueprint also cut all state funding for and gave the governor authority to shut down any school system that desegregated. Together, the package of 13 segregationist statutes came to be known as the “Stanley Plan.”

Virginia’s top elected officials made it clear: they would shut down the schools before they would integrate.

Popular Opposition to Integration

It wasn’t just the Richmond power structure that was strongly opposed to getting rid of segregated schools. Many, if not most, white Virginians were opposed to desegregation in 1954. Here we have a selection of pro-segregation literature gathered locally primarily by Barbara Marx, a German-born NAACP member and activist who lived in Arlington during the 1950s.

A warning: The documents linked on this page contain some fairly vitriolic racism. Please be advised. They are included because it is impossible to fully understand segregation without understanding racism. Their inclusion on this site is in no way an endorsement of their content.

One thing that might be jarring for contemporary readers is the way that many of these documents rely strongly on Christian-inflected rhetoric. After all, many leaders of the Civil Rights movement were Christian ministers themselves. So why is this?

There is a long tradition of religious justification for racism that goes back to America’s history of slavery. Some have argued that Black people are the descendants of Canaan, the grandson of Noah who was cursed and cast out by his grandfather for his father Ham’s transgression. The descendants of Canaan were said to be cursed with eternal slavery.

The Old Testament has frequent mentions of slavery, and the idea of a people doomed to eternal slavery likely appealed to religious individuals looking for a justification for the institution of chattel slavery.

It is also important to remember that this literature was produced in the early 1950s, during the early years of the Cold War. The American Communist Party had been one of the most consistently racially progressive political organizations in the United States throughout the 1920s and 1930s. Many segregationists argued that integration was a Communist plan, a Soviet plot to destroy America from within. It was not uncommon for segregationists to describe the NAACP in particular as a Communist organization.

Christian Americanism was offered as a healthy alternative to Communist Atheism, and for this reason, Christian justifications of the racial order under Jim Crow were seen as a perfect rebuttal to Soviet criticisms of America’s system of racial apartheid.

Arlington School Board Reacts to the Brown Decision

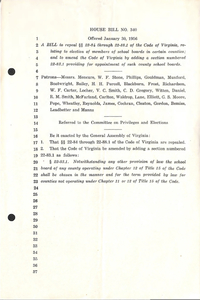

House Bill No. 340 Offered. Bill to repeal 22-84 through 22-88.1 of the Code of Virginia relating to the election of members of school boards in certain counties. This bill was aimed at the elected members of the Arlington County School Board, disbanding the elected board and replacing it with one that was appointed.

Just ten days after the Brown decision, the Arlington County School Board called for a “Committee to Study Problems of Integration in the Arlington Public School District,” to look at how best to comply with the ruling. The committee included Black and white clergy, teachers, and three NAACP members: Edith Burton, Mary Shirley, and Geraldine Davis. Elizabeth Campbell, a white liberal and pro-integration member of the School Board headed the committee.

By January 1956, the committee had a preliminary plan in place to desegregate the school system. The committee’s proposal was not particularly bold or far-reaching. It favored only a small number of students desegregating the schools, at least at first. It was a conservative, incremental strategy.

It was also one that had the disadvantage of pleasing very few. Some integrationists, such as Virginia NAACP President E.B. Henderson, saw it as trying to do the minimum amount of integration legally required under Brown, to reassure the New York guarantors of an upcoming school bond issue.

On the other side was the Byrd machine in Richmond. Less than a month after the Integration Committee issued its plan, legislation was introduced in the General Assembly to strip Arlington County of the right to have an elected school board. At the time, Arlington was the only county in the country whose school board was popularly elected.

The bill passed, and in July, 1956, the Arlington School Board was replaced with a new group of appointees, chosen by the County Board. This new panel was considerably more sympathetic to the cause of segregation, with a membership that included few racial moderates and some outspoken segregationists.

Arlington’s Racial Moderates

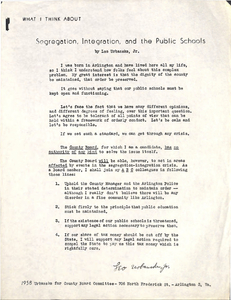

What I Think About Segregation, Integration, and the Public Schools, by Leo Ubanske. Document by County Board member Leo Urbanske stating his commitment to public schools and Arlington County.

Due to a particular set of historical circumstances, Arlington’s population differed from much of Virginia in terms of racial attitudes. Prior to the 1930s, the county had been primarily rural. The expansion of the federal government during the New Deal, followed by even more federal growth after America’s entry into World War II, quickly reshaped the county.

People from all over the country flocked to the Washington area for new jobs, and Arlington was an affordable place to live. The completion of the Pentagon in early 1943 made the military one of the largest employers in the county.

This influx included a large number of new residents from the less-segregated North. Likewise, the importance of the defense industry and the military to Arlington meant that more people had experienced some degree of desegregation already—executive orders signed by President Roosevelt in 1941 and President Truman in 1948 respectively barred racial discrimination by defense contractors and ended segregation within the military.

The result was that many white residents in Arlington could be called “racial moderates.” Many may not have minded segregated schools—and some may have indeed favored segregation—but they were far more concerned with the prospect of the public school system being closed down altogether.

Because Arlington’s economy was so dependent on the federal government, political participation was complicated. The Hatch Act of 1939 limited the participation of federal workers in partisan politics, so Arlington residents created “non-partisan” groups to advocate for local change, with names like “The Citizens Committee,” and “Arlingtonians for a Better County,” “ABC” as it came to be known.

Prior to the influx of newcomers, the public schools in Arlington had a poor reputation, and those who could manage sent their children to D.C. or boarding schools. When people from outside the South came to Arlington for government jobs, they wanted their children to have strong public schools, like the ones they grew up attending. Many supporters of ABC shared such memories. As a result, the group made school improvement a major issue.

Some ABC politicians viewed the threat of wholesale closure of the public school system to be an almost existential threat. It was due to an ABC campaign that Arlington won the right to have an elected school board in January of 1949. They did not appreciate the state taking that right away.

The new, appointed School Board would be repeatedly confronted with the fact that for many Arlingtonians, keeping the schools open was more important than maintaining segregation.

1956-1959: The Road to Stratford

By 1956, Virginia seemed in many ways to be no closer to desegregating its public schools than it had before Brown v. Board of Education. The NAACP decided it was time to put forward lawsuits to try to make the Commonwealth comply with Brown. The case of Clarissa Thompson v. the County School Board of Arlington was part of an effort to push Virginia school districts where segregation was most vulnerable. The case dragged on, however, bogged down in bureaucracy and legal back-and-forth.

Meanwhile, white racial moderates in the county formed the Arlington Committee to Preserve Public Schools, which later would grow into a statewide organization, the Virginia Committee to Preserve Public Schools. This organization was distinctly agnostic toward the issue of segregation and simply advocated against the closing of public schools, bringing pressure to bear on government officials.

On February 2, 1959, having exhausted all legal and bureaucratic maneuvers, Arlington Public Schools had no choice but to admit four Black pupils into the previously all-white Stratford Junior High School. Perhaps surprisingly, this occurred without protests or negative incident. The state did not shut down Arlington County Public Schools. It is largely remembered, as an oft-repeated headline described it, as “the day nothing happened.”

1956: Clarissa Thompson v. the County School Board of Arlington is filed

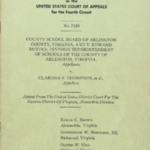

Court Case, Clarissa S. Thompson, et al. v. County School Board Of Arlington County, Virginia, et al, Civil 1341

As the second anniversary of the Brown decision approached, opponents of segregation in Arlington had seen almost no progress in the implementation of the ruling. Finally, on May 17, 1956—the second anniversary of the original Brown ruling—Virginia NAACP lawyer Edwin C. Brown filed suit against Arlington County’s School Board. The NAACP filed similar suits in Front Royal, Newport News, Norfolk, Charlottesville, and Warren County.

Brief On Behalf Of Appellees For Case No. 7310 In The United States Court Of Appeals For The United States District Court For The Eastern District Of Virginia, Alexandria Division

Suits were filed in these places because they had particular things in common—they were areas with low Black populations, with larger than average populations of white racial moderates, and where the Byrd machine was absent or not particularly powerful. These shared traits, the thinking went, meant that they might be more open to desegregation.

Clarissa Thompson, daughter of NAACP member Ethel Thompson, was the first name on the suit, but it was brought on behalf of several students, including the children of civil rights activists Lesley and Dorothy Hamm and the children of Barbara Marx, one of the few active white members of the Arlington NAACP.

The child of another white family was initially named in the suit, but that family dropped out after two weeks after receiving telephoned threats. Barbara Marx, who had been in Nazi Germany as a young woman, was undeterred by similar threats.

Timeline and chronological series of events, court decisions, etc., relating to Arlington County and desegregation of public schools.

Federal Judge Albert Bryan, who had been the first judge on the Constance Carter case, ordered the schools to be integrated, but the particular wording of his injunction stated that the students could only come back to the court to seek enforcement of that order if they could prove that they had gone through all appropriate bureaucratic channels. This included the Commonwealth’s Pupil Placement Board, a body that had been created in Richmond that summer and had ultimate power over placement of students.

The case at that point was plunged into a complex set of appeals and bureaucratic red tape that would last two and a half years.

1958: Arlington Committee to Preserve Public Schools

As the NAACP pressed on with the Thompson case with repeated success, the moment was quickly approaching when the Commonwealth, to keep schools segregated, would have to use the only other tool at its disposal—closing the schools.

Flyer: "To All Arlington Citizens": announcing the formation of the "interim Organizing Committee to Preserve Public Schools", May 11, 1958.

On May 1, 1958, the Arlington Committee to Preserve Public Schools, recently formed by a small group of white racial moderates and integrationists, issued a statement that expressed a willingness to “pursue every legal means to keep public schools open.” The group further expressed absolute agnosticism about the issue of segregation and a distrust of the idea of giving public funds to private education.

By the time of the following month’s meeting of the organization, the group numbered over 700 members.

Over the next few months, the organization served as an important point of communication for those opposed to closing schools, including concerned citizens, administrators, and a majority of the county’s parent-teacher associations.

The Arlington Committee to Preserve Public Schools was all white, and in limiting membership to white people it was able to gather and rally a disparate group of white racial moderates. Dr. O. Glenn Stahl, president of the organization, claimed that it represented:

a very broad segment of the population, including many, many people who much prefer to have segregation. Therefore it’s not an integrationist group. But it is concerned about keeping the public schools open and not letting the public schools be sacrificed in order to settle the question of integration.

By assembling a large group of racial moderates who were more concerned with keeping schools open than with one another’s views on integration, the Arlington Committee to Preserve Public Schools was able to exert pressure on local and state politicians. They made closing the schools—the “nuclear option” upon which Massive Resistance depended—a far less attractive option to the appointed county School Board and state officials.

While the NAACP used the courts to pressure the schools to desegregate, the Committee pressured the segregationist-leaning School Board to commit to keeping the schools open. The organization would soon grow into a statewide one, the Virginia Committee to Preserve Public Schools, which would use much the same strategy throughout the Commonwealth.

View more Arlington Committee to Preserve Public Schools documents on the Project DAPS site.

February 2, 1959

By January of 1959, the state had exhausted all its legal countermeasures to the Thompson case. Many Arlington parents were still worried that the School Board would choose to close the schools rather than desegregate. The final nail in the coffin of Massive Resistance came on January 19, when the Virginia Supreme Court struck down the school closure law, ruling that it violated the guarantee of a free public education in the Virginia Constitution.

On January 22, 1959, the School Board held a special meeting and announced that Stratford Junior High would be the first school to be desegregated.

Finally, on February 2, four students—Gloria Thompson, Ronald Deskins, Lance Newman (oral history), and Michael Jones (oral history)—walked up to Stratford just after the first bell at 8:45 a.m. The four students lived nearby but gathered at a single house that morning before walking the last bit together. Close to 100 police officers formed a cordon along the road leading to the school. The memory was still fresh of the angry white mobs that formed in Little Rock, Arkansas when that school was desegregated a little more than a year earlier.

Article by David L. Krupsaw, Chairman of the Arlington County Board, "The Day Nothing Happened", The ADL Bulletin, February 1959.

Ultimately, the desegregation of Stratford arrived without incident. There were no angry mobs, no shouted words, no brickbats. Stratford principal Claude Richmond—the same man who, as principal of Washington-Lee, had turned away Constance Carter in 1947—welcomed the students. By all accounts, Richmond made every effort for the new students to feel welcome and safe.

Despite the police and reporters, it was essentially a normal day at school. The newsletter of the Anti-Defamation League, reporting on the desegregation of Arlington schools, ran the headline: “The Day Nothing Happened.” And that seems to have been the case, for the most part.

After Stratford

When four Black students entered Stratford Junior High School for the first time, it did not signal an end to segregation in Virginia, or even in Arlington. Desegregation is not integration. While Arlington had taken the first step by allowing a few students to break through the wall of segregation, most students would continue to attend largely segregated schools. Indeed, it wasn’t until 1971 that Arlington adopted a pupil-placement system that was sufficiently non-race-based to gain court approval.

Moreover, many places in Arlington still excluded Blacks, from lunch counters to taxis, and even the local hospital.

Desegregation is Not Integration

On December 27, 1962, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. said in an address to a church conference in Nashville, “…desegregation alone is empty and shallow. We must always be aware of the fact that our ultimate goal is integration, and that desegregation is only a first step on the road to the good society.”

Desegregation and integration are two very different things. “Desegregation” occurs when a small opportunity allows some people past the wall of segregation. “Integration” occurs when a population reaches parity when the wall of segregation no longer exists.

Gloria Thompson, Michael Jones, Ronald Deskins, and Lance Newman entered Stratford Junior High School in 1959. Over the next few years, other schools would begin to desegregate. But it is important not to confuse that desegregation with integration. It took years before Arlington approached true integration of its public schools. It required not just gradual change over time but more advocacy, struggle, and at least one more major lawsuit.

Moreover, much of the county outside of the school system was still very much segregated. That, too, took time, campaigning, and organizing to change.

The documents collected here represent the reality of the segregation that persisted in Arlington years after Stratford: from bowling alleys to housing to the local hospital.

A 1963 broadside titled “The Negro Citizen in Arlington” shows the true depth of the segregation that remained. Among the injustices that the document catalogs: all the movie theaters and drive-ins in Arlington were whites-only; there were no decent sit-down restaurants that allowed Blacks to eat in their dining rooms; the maternity ward at Arlington Hospital would not admit Black mothers.

The document closes with a defiant tone, pointing to the constant precarious state of Black life in Arlington, even in the face of growing legal equality:

It is the uncertainty about so many aspects of his life that is trying for a Negro in Arlington. Some years ago he knew exactly what his limitations were. He didn’t like being limited but he knew what to expect. Now he is tired of being unknowing about his status.

The Negro knows that merit hiring permits him to apply for and, if he is qualified, to receive a Civil Service job in the Arlington community. He does not know to what extent racial prejudice may influence the decisions of the department head who is responsible for his promotions.

The Negro knows that by Federal Law his children are now guaranteed public school education on a non-segregated basis. He does not know how long it will be before Negroes in Arlington can expect that without individual court appeals, their children will all be accepted in neighborhood schools just as other children are.

1959-1962: Desegregating Sports and Dances

Even with the schools technically desegregated, certain elements of day-to-day school life were still segregated. Dances and athletics, in particular, were for a period eliminated at all desegregated schools. Such activities were a particular source of fear for segregationists, as both put students’ bodies in close proximity.

For people who opposed integrated schools due to the racist specter of miscegenation—who feared that integrated schools threatened “racial purity” by encouraging mixed-race relationships—the idea of integrated sports, and especially integrated dances, was particularly worrisome.

This refusal to desegregate certain elements of school life, even in the face of Judge Bryan’s order, was supported by a Massive Resistance-era law passed in Richmond. School Board member and attorney L. Lee Bean read the law—Joint Resolution #97—during a School Board meeting on September 21, 1959: “No athletic team of any public free school should engage in any athletic contest of any nature within the State of Virginia with another team on which persons of the white and colored race are members…” The Board voted that day to cease all athletic events. The same day, they also voted to stop all school-sponsored dances.

The Board reinstated athletic programs for the 1961-1962 school year, but it was even longer before school dances came back. Meanwhile, other groups in Arlington provided space and opportunity for these important social functions for school children. In an oral history in the collection of the Arlington Public Library’s Center for Local History, School Board member James Stockard recalled that Mount Olivet United Methodist Church held dances during the school system’s ban.

In another oral history, Constance McAdam, who at the time worked in the county’s Department of Parks and Recreation, discussed a program of integrated dances for teenagers sponsored by the Parks department between 1959 and 1962. McAdam recalls “tension” at some events during the first few years—they even had the police come to keep an eye on things—but reported that the tensions dissipated to a degree over time.

Read related documents on the Project DAPS site.

1961: Drew Elementary Expansion

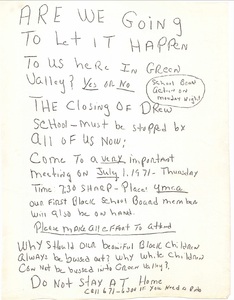

Packet of papers related to a July 1, 1971 meeting about the Drew Elementary desegregation plan. Include a statement from a group of local ministers, organizing phone list, and extracts from the board action.

Only a few years after the desegregation of Stratford, the next issue to divide the county over race and the school system came from what might seem an unlikely source: a portion of a planned bond issue to improve and expand Drew Elementary School in Arlington’s historically Black Nauck/Green Valley neighborhood.

In 1961, the School Board proposed that a section of an upcoming bond issue be put toward a 22-room addition to the extant Drew School and a consolidation of the Drew, Kemper, and Drew Annex schools, which were all in the same general neighborhood. The local NAACP, the Nauck Civic Association, and the Jennie Dean Community Center, among others, opposed the plan.

It might strike the reader as strange that the NAACP would in 1961 be spearheading an effort to oppose improvements to a Black school when, as recently as the Carter case in 1950, they had been suing the School Board for exactly that. But Brown v. Board of Education changed everything, especially the NAACP’s approach to how best to improve schooling for Black students.

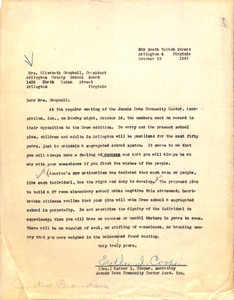

Letter from Esther Cooper, Jennie Dean Community Center Association, about opposition to Drew School expansion, October 18, 1961

Prior to Brown, the Plessy ruling was still the law of the land. “Separate but equal” was viewed, legally, as fair and constitutional and was used as a standard for judging whether a law or policy was legal under the 14th Amendment. Facing this reality, the NAACP’s best strategy was to prove that facilities and educational opportunities for Black students were unequal.

After Brown, however, the NAACP’s goals changed. Integration was seen as the best means to attain quality education for Black students—they could simply go to the schools that were already systemically better.

The Black communities in south Arlington were not completely unified around the rejection of the Drew Elementary expansion, however. For some in these communities, it seemed a good idea to improve and expand the neighborhood elementary school, even if it was segregated.

The NAACP responded with an education campaign. The expansion, the group argued, would make the school too large to be manageable, at almost 1,200 students. This was by far larger than any other elementary school in the county. They pointed to a recommendation from the National Educational Association that elementary schools should ideally be limited to around five hundred students. Even with 22 new rooms, they further argued, 1,200 students would result in an unmanageable number of students in each classroom.

Opponents of the expansion suggested an alternative: a new school to be built about a mile northeast of Drew on the site of Douglas Park. Because of its location, this new school would draw equally from nearby white and Black neighborhoods and would lessen the overcrowding of Drew and Kemper.

Typewritten Sermon, A Newcomer Looks at Drew-Kemper, Rev. Edward Redman, Unitarian Church of Arlington, October 29, 1961.

As the NAACP attempted outreach within the Black community, white allies of desegregation tried to spread the same message to white Arlingtonians. The Reverend Richard H. Redman, minister of the Unitarian Church of Arlington, delivered a sermon on the topic in October of 1961.

The movement against the Drew expansion found its most powerful white proponent in School Board member James Stockard. He went on record calling the expansion “discriminatory” and a “segregation move.” In one Board meeting, Stockard declared that if the plans for expansion went forward he would “have to exert [m]y full influence in this county toward defeat of the school bond issue.”

NAACP representative Robert Alexander called out in response, “At least there’s one Christian in the house!”

Ultimately, however, Stockard was outnumbered. The Board approved the measure, and when it went up for a vote before the county’s general population on November 7, 1961, the bond issue was approved. The county would move forward with plans for the Drew expansion.

Construction of the Drew expansion began in 1963.

1971: Desegregating Drew Elementary

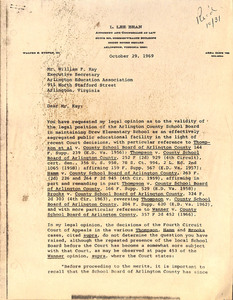

Letter from an Arlington attorney, Lee Bean, to William F. Kay, executive secretary of the Arlington Education Association advising the validity of the Drew School's de facto segregation. Letter makes comparisons to many national and local court cases regarding segregation in public schools. October 19, 1969

By 1969, Arlington’s junior and senior high schools were all desegregated. Hoffman-Boston Junior-Senior High School had closed in 1964, and Black students were placed in formerly all-white schools. At the elementary school level, however, there were still two schools that were virtually entirely Black.

The recently expanded Drew Elementary School and Hoffman-Boston Elementary School were both located in Arlington’s largest Black community. There had only been a handful of white students who attended either school in the ten years after public schools in Arlington ostensibly desegregated, and those students were only placed in the schools after their parents had requested admission.

On December 11, 1969, a group of around thirty parents of Drew students met at the headquarters of the Arlington Community Action Program and decided to ask the School Board at its January meeting “why it [was] ignoring the law of the land.” Chief among the parents’ concerns was that students from Drew were having considerably more difficulty adjusting to desegregated junior high compared with other Black students in the county who had attended integrated elementary schools.

Lawyer Thomas R. Monroe and education expert Dr. Donald K. Sharpes were also in attendance and explained to the group that they had been pressing the issue of desegregating Drew with the School Board since May. They vowed to “exhaust all channels of communication” with the Board and, if that didn’t work, to sue. A community task force was set up to explore the issue with other Nauck residents.

John K. Hart, Et Al, vs. County School Board Of Arlington County, Virginia, Et Al, Interrogatories, June 1970

In May of 1970, feeling that the School Board was still not listening to the community’s concerns, ten parents filed a class-action suit on behalf of sixteen Drew students: John E. Hart et al. v. County School Board of Arlington County, Virginia.

Just a little more than a month before the trial, on June 28, 1971, the School Board announced that it had arrived at a plan to desegregate Drew and Hoffman-Boston. Students in grades one through six of the two schools would be bused to other elementary schools throughout the district.

Students would be assigned to new schools in a way that tried to keep the Black population of each school as nearly as possible to 11% of the school’s total enrollment. (At this time Black people were about 11% of Arlington’s population.)

This new plan was not satisfactory to many in the community who felt it was essentially a plan to bus-only the Black students. They argued that the plan put too much of the burden of desegregation on the same children who had already been forced to endure the indignities of segregation. This argument was pressed in an amended complaint before Judge Oren R. Lewis on August 10, 1971.

Letter/Document concerning remedy/remedies to the problem of school children who've been isolated from most other students their age because of segregation, zoning lines, etc. Advocates for a "compensatory education" program to help isolated students make up for time lost. unattributed and undated

Lewis was unconvinced. He quoted previous case law stating that whether or not the district could have closed down different schools was immaterial; the question was “whether the Board's decision is so unfair that it amounts to invidious discrimination in violation of the equal protection clause.”

Lewis saw no such “invidious discrimination” in the desegregation plan and ruled in the School Board’s favor. “If Arlington is to convert to a unitary system, and the Supreme Court has decreed that it must—there will of necessity be some busing. The limited busing of the Drew-Hoffman-Boston children, here required, risks neither the health of the children nor significantly impinges on the educational process.”

He further pronounced that “The Arlington County School Board has now fully complied with the Supreme Court decision in Brown…Arlington will have neither black nor white schools—just schools.”

This decision was upheld on appeal on May 1, 1972.

Conclusion

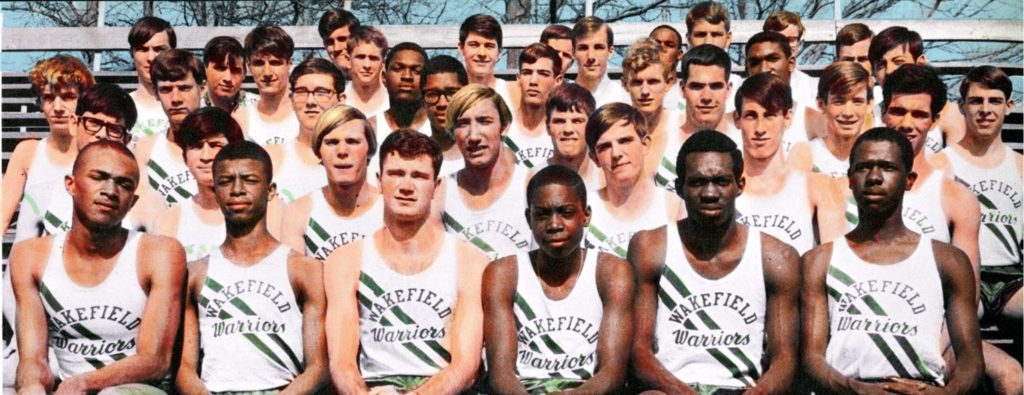

Wakefield Warriors, 1968

Arlington desegregated and was the first public school system to do so in the Commonwealth of Virginia. This is often a point of pride for Arlingtonians, and rightly so.

But it is also important to remember that it took almost eighteen years of activism from the NAACP and Arlington’s Black communities to get to that point. And that it took almost five years for Arlington to desegregate their first school after Brown v. Board of Education.

Likewise, it took another twelve years after the desegregation of Stratford before Arlington had a desegregation plan in place sufficient for a court to consider it in compliance with Brown v. Board of Education.

The story told by the documents presented on this site is one that is complex and occasionally frustrating. But it is a story of progress. Not progress in the form of some slow, natural process, but the progress that was hard-won after years of pressure, political maneuvering, and lawsuits by the NAACP and other organizations within the community.

What is heartening is that this sort of pressure worked--that it changed minds and hearts and the material reality of Black students in the county.

It is also heartening to note the role of the white racial moderates in the county. The people who formed the Arlington Committee to Preserve Public Schools were not of one mind about desegregation. Some members were opposed to it. But they felt that keeping the public schools open was more important than maintaining segregation. The lesson here is that, with enough pressure and activism, the center can, indeed, be moved. That minds can be changed when you show them how they, too, have a stake in the decisions made.

We would love to hear from you. How does this story relate to your story?

We hope that this exhibit and these documents will become the start of a broader conversation about segregation in its many forms, about what integration truly means, and about race in Arlington County more broadly.

I pride myself on keeping up-to-date and knowledgeable about all our great aspects that make Arlington THE #1 COUNTY of 3000+ in our nation. I now live in Halls Hill since 2009…so it was a point of pride that the 4 that integration Stratford 2/4/59 came from my neighbors.

So I knew generally about this story, yet not in the great detail and history that you have put hard work into writing! My church has in August and 1/21/18 having Adult Forums on racism, so this is quite timely beyond MLK Day! (If he wasn’t assassinated, MLK Jr. likely would have been our first African American President.)

My wife and I were both members of the Washington-Lee class of 1960 and were Seniors in 1959-1960, the first year of desegregation at W-L (We agree that it was Desegregation, not Integration). There were three black students in a school of 2,700 students and we certainly believe that like Stratford, it was a “Day that Nothing Happened”. We don’t recall any police, reporters or any other special attention.

I would like to make some comments concerning the above section on “1959-1962: Desegregating Sports and Dances”. I’m sure that it was well researched and I can’t speak to specific policy actions taken by the County School Board. However, we can speak to what actually happened, that year, at the school. I checked our yearbook and it did indicate that the School Board said that “the schools could continue their clubs and athletic events, but could sponsor no dances” (page 10). Reading that policy today was the first time I had noticed in the yearbook.

During that school year, all athletic teams had a full season of scheduled events and there were a number of school sponsored dances. There are a number of pictures in the yearbook that show participation in sporting events and school dances. If there was any change in policy, at the county level, it certainly wasn’t reflected in the day-to-day activities of the school. We might also add that the dances sponsored by the school crew team, at the Potomac Boat Club, featured bands with black singers and instrumentalists, and they were always extremely popular with the student body.

This is incredible! You all clearly put a lot of effort into making this article. Thank you for the history lesson, APL!

I read this outstanding piece of historical research on Martin Luther King Day. It conveys a complicated story with lucidity, depth, and fairness. To read the debates and advocacy of that time and in this place I live really brought home what the larger civil rights movement meant for our country. And it illuminates how positive social change occurred, despite the limitations we recognize today. Our moral and political challenges today are different – and the same. And we are similarly called to action.

Thanks to our public library system, for making this history available.