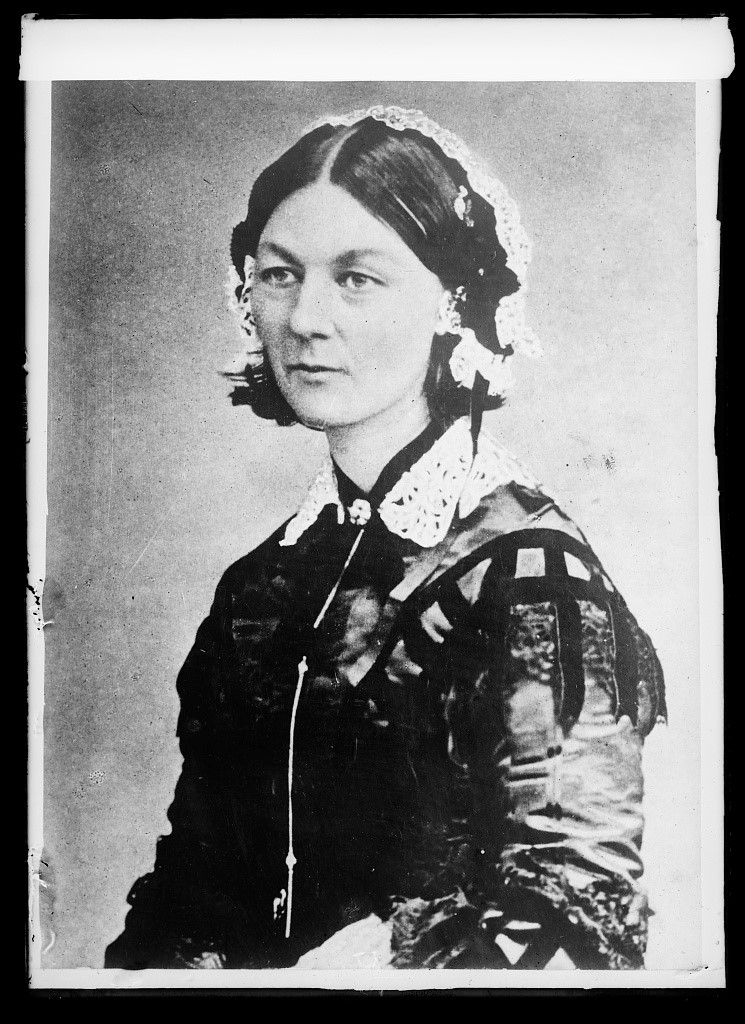

Florence Nightingale (1820-1910)

This week we're honoring the health care and public health people working tirelessly to protect our communities in the midst of the COVID-19 crisis.

Florence Nightingale is one of the pioneers of modern medicine. She is known particularly for the role she played in improving hospital sanitation, promoting social reform and founding the modern nursing profession.

Florence Nightingale, date unknown. Image from the Library of Congress.

Early Years

Nightingale was born on May 12, 1820, in Florence, Italy to English parents. The Nightingale family was very well-off, and Florence was homeschooled by her father, who was under the assumption that she would eventually marry a similarly wealthy man.

This plan went by the wayside when, as a teenager, Nightingale received a religious calling to help the poor and sick. From a young age, she had been active in philanthropy, serving the ill in the village neighboring her family’s home.

Though her parents disapproved of Nightingale's vision, they eventually agreed to send her to Germany to study. From there, she went on to train in Paris with the Sisters of Mercy before returning to England. This led her to take on a nursing job in the early 1850s at a Harley Street hospital for ailing “gentlewomen.” She excelled in this role and was eventually promoted to the hospital superintendent. During this time, she also volunteered at a hospital in Middlesex, where a cholera outbreak was exacerbated by unsanitary conditions. Nightingale instituted new hygiene practices there, which significantly lowered the death rate of the hospital.

Florence Nightingale, 1854. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Kingdom of Hell

In 1853, England entered the Crimean War. After a series of scandals and complaints around battlefield medical care, the Secretary of War called on Nightingale to manage a group of nurses that would treat soldiers on site. She began her appointment on November 4, 1854, when she and 38 other nurses sailed to a British camp near Constantinople. The conditions they found shocked Nightingale, who dubbed it, “the kingdom of Hell.” The military hospital was set up on top of a large cesspool, which had tainted the water supplies, and the place was incredibly overcrowded. Patients were strewn about in disarray, and the most basic supplies and cleanliness protocols were absent. More soldiers were ill from infectious diseases than from injuries sustained on the battlefield.

The male doctors there initially resisted the all-female nursing team, as there had been no female nurses stationed in the Crimea up until this point, and refused to allow them to work. However, they eventually accepted the women into the fold as the number of patients began to overwhelm them.

The team of nurses transformed the military hospital under Nightingale’s leadership, bringing supplies, sanitary practices, and individualized care to their patients. In addition to improving the cleanliness of the hospital, they also established a proper hospital kitchen, laundry room, and classroom for the soldiers. Among Nightingale’s innovations was her insistence that the hospital have proper ventilation, which has influenced hospital design into the modern-day.

After arriving, the nurses brought the death rate at the hospital down from 40 percent to 2 percent. This period was also the origin of Nightingale’s nickname “the lady with the lamp” – she was known for carrying a lamp in the evenings to check on the conditions of the soldiers in her care.

The Florence Nightingale Hospital near Constantinople. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Beyond the Battlefield

Nightingale’s role in public health did not end when the war did, however. Upon returning to England, in 1856 she presented her wartime experiences and medical data to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, which resulted in the formation of a Royal Commission to improve the health of the British Army. She then went on to establish the Army Medical College in 1859, and opened the Nightingale Training School at St. Thomas’ Hospital the following year.

During her career, Nightingale penned many books and pamphlets on the subject of nursing and managing safe hospital environments, such as “Notes on Nursing: What it is, and What it is Not.” She was also the first female member of the Royal Statistical Society, elected in 1858.

Nightingale’s impact also extended to the United States, where she was frequently consulted on how to best manage field hospitals during the Civil War, influencing medical volunteers such as Clara Barton.

“Grave of Florence Nightingale near Ramsey, England. American Red Cross workers place wreath,” September 9, 1919. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Legacy

Florence Nightingale died on August 13, 1910. Her work shaped modern nursing practices and set a precedent for medical treatment and policies today.

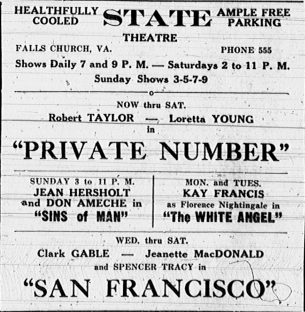

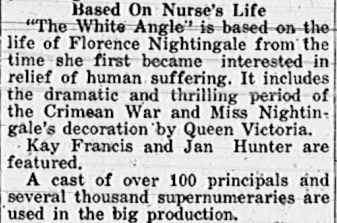

“The Lady with the Lamp's” legacy lives on in many forms, as a key figure in the development of public health practices, and a figure of inspiration: in 1936, a play based on her life, "The White Angel," was performed at the State Theatre in Falls Church.

Advertisements for a 1936 performance of “The White Angel,” a play based on Florence Nightingale’s life, held at the State Theatre in Falls Church. From The Northern Virginia Sun, August 13, 1936.

Learn More

The Library has numerous books about Florence Nightingale available on OverDrive:

“Florence Nightingale: The Angel of the Crimea, a Story for Young People,” by Laura E. Richards

“Florence Nightingale,” from the Famous People Great Events series, by Emma Fischel

“Nursing: What it is, and What it is Not,” by Florence Nightingale.

The Florence Nightingale Museum has a variety of online exhibits about Nightingale’s life and work.

The United Kingdom’s National Archives has a series of lesson plans that focus on Florence Nightingale’s legacy.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Charlie Clark Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields