Arlington has a history of dedicated community members fighting against racism, prejudice, and injustice through protests, community organizing, and legal work.

June 10, 1960, Gwendolyn Green (later Britt) and David Hartsough sit at the People’s Drug Store counter. Protests such as this happened at counters in seven locations in Arlington including two in Shirlington. DC Public Library, Star Collection, ©Washington Post. Read more about Shirlington.

Collected here are stories about some of those individuals and groups, told through documents donated to the Center for Local History. This is only a small sampling of stories that make up the history of Arlington’s activist community, and we are dedicated to telling the stories of those who have fought in Arlington’s continued struggles against inequalities.

The CLH invites you to play an active role in documenting our history by donating physical and/or digital materials for the Community Archives.

Dorothy Hamm was an Arlingtonian at the forefront of the civil rights movement and leader of the efforts to desegregate the county’s schools and theaters.

Image courtesy of Carmela Hamm, from the Library of Virginia.

Excerpt:

In 1956, Hamm, along with her husband, became plaintiffs in the first civil action case filed to integrate the Arlington Public School system. When no action towards integration had been taken a year after the suit was filed, Hamm and her husband took their oldest son, Edward Leslie Jr., to enroll at Stratford Junior High School. They, and other African-American students who attempted to enroll in the still segregated Arlington schools, were denied admission that year. In September 1957, a few days after the opening of the school year, crosses were burned on the lawns of two Arlington families, and at the Calloway United Methodist Church, a central location for organizers in the effort to desegregate the schools, and a site of workshops held by ministers, lawyers, and educators preparing parents and students for school integration.

Over the course of this process, Hamm recalled in interviews many experiences with discrimination and intimidation.

Two stories in this list chronicle the struggle to desegregate Arlington Public Schools told through oral history interviews, historical documents, and legal proceedings.

You can also learn more about the people and events that made up this historic effort in the library’s online exhibition, Project DAPS.

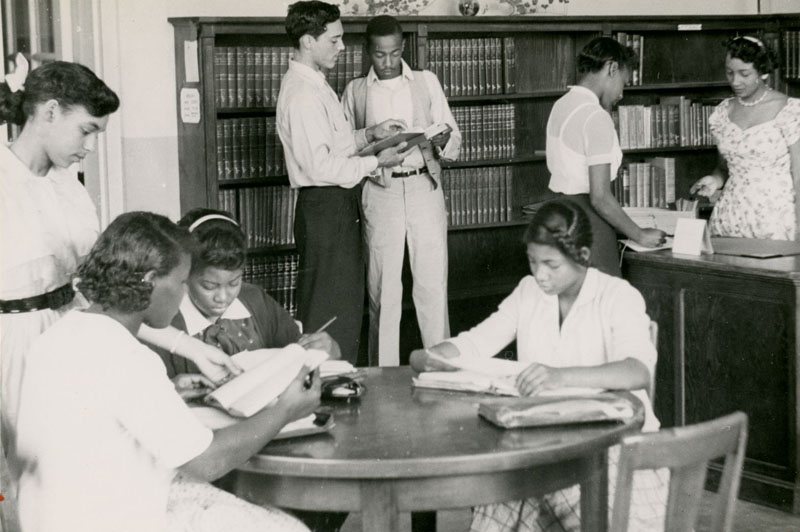

African American students reading in the library.

Excerpt:

In this clip from 1986, Hamm shared her experience trying to register her son for school at Stratford and her activity in lawsuits to desegregate public facilities in Arlington County.

Dorothy Hamm has been honored by the County with the naming of a new middle school in Cherrydale, the Dorothy Hamm Middle School, which opened in September 2019.

Ronald Deskins, Michael Jones, Lance Newman, and Gloria Thompson walked into Stratford Junior High School on February 2, 1959.

Excerpt:

At 8:45 a.m. on February 2, 1959, four young students from the nearby Hall’s Hill neighborhood entered Stratford Junior High School in Arlington, Virginia.

When they stepped into Stratford that day, they became the first students to desegregate a public school in the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Many Arlingtonians know that theirs was the first county in Virginia to desegregate. It is a point of pride. But it’s not the whole story.

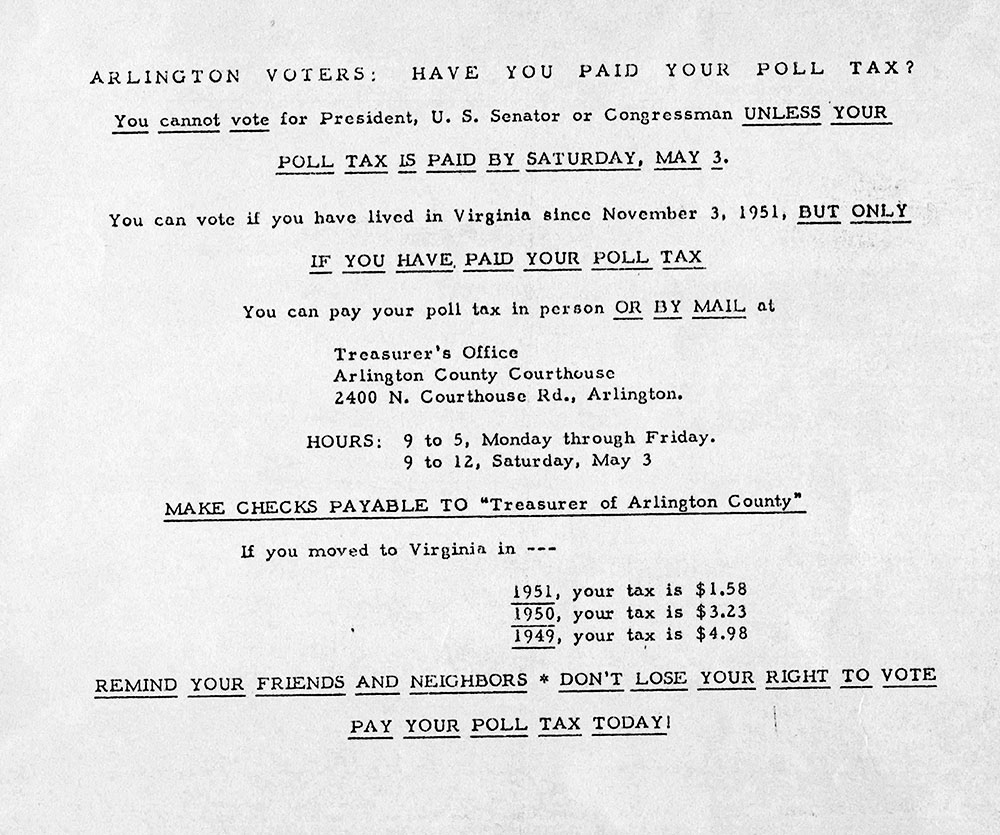

“If You Don’t Vote, You Don’t Count” looks at the poll taxes imposed to restrict voters and prevent African Americans from voting in the county, and the actions taken by local activists to combat this voter suppression.

1951 flyer telling Arlington residents how to pay their poll tax in order to vote in the upcoming election.

Excerpt:

In 1876, after the Fifteenth Amendment granted African-Americans the right to vote, Virginia passed a poll tax to restrict African-American men from voting. Although this law was repealed in 1882, in 1901 the Virginia General Assembly called for a new constitution with the explicit purpose to secure the right of suffrage of the state's white men, and to take away the right to vote from anyone in the state who wasn't white.

The new constitution, which passed in 1902, reinstated the poll tax. This required voters to pay a tax of $1.50 six months prior to an election for each of the three years preceding an election. This disenfranchised approximately 90% of the black men and, counter to the intentions of those who had drafted the new constitution, nearly 50% of the white men who had previously been registered to vote in Virginia. The 1902 constitution also created an administrative structure that was difficult for any average citizen to navigate, further disenfranchising many poor men.

Next, read about efforts to continue the efforts of desegregation beyond the schools when a group of Arlington activists drafted their own Declaration of Civil Rights.

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964 into law as various Civil Rights leaders look on, including the Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr. Photo courtesy of the LBJ Library, photo by Cecil Stoughton.

Excerpt:

Published just a little over a year after Arlington became the first school district in Virginia to desegregate, this document is a powerful reminder that despite those four students integrating Stratford Junior High in 1959, segregation in Arlington was still far from over. Many institutions in Arlington remained segregated, and this document specifically enumerates some of them: from sit-down restaurants and movie theaters to maternity wards, to playgrounds and pony rides for children.

Item six contains one of the leaflet’s most powerful observations: “It is the uncertainty about so many aspects of his life that is trying for a Negro in Arlington. Some years ago he knew exactly what his limitations were. He didn’t like being limited but he knew what to expect. Now he is tired of being unknowing about his status.” In the years leading up to the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964, this was indeed the reality for many Blacks in the South.

To learn more about Arlington's history, visit the Center for Local History on the first floor of the Central Library.

Do you have a question about this story or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields