Created by Arlington's Black Residents to Serve Their Community During Segregation

What follows is the first in-depth history of the Holmes Library, and of segregated library services in Arlington County. Drawn from primary source material held in the Arlington Community Archives as well as the work of researchers at other regional libraries, this history aims to honor the volunteer-led efforts of Arlington’s Black community, and to answer two critical questions: When and why did Arlington desegregate its public libraries?

The story of Arlington’s first library for Black patrons is one of an extraordinary grassroots effort led by members of Arlington’s Black community.

The Henry Louis Holmes Library was established in 1940 as a community-led facility to fill in the gap created by segregationist County and state policies. In order to bring books and material resources to the County’s Black residents who had been denied such services, a group of Black Arlingtonians worked together in order to establish an independent branch.

The Holmes Library would later join the still-segregated County library system as the only branch available to Black Arlingtonians until its closure in 1949, and the subsequent desegregation of Arlington's libraries in 1950.

An Exclusionary System

Arlington’s at-large library system began as a series of volunteer-run organizations, which were later incorporated into the County in 1937. Volunteer and civic groups across the County’s neighborhoods started five local branches in the early 20th century: Glencarlyn, Cherrydale, Clarendon, Aurora Hills, and Arlington (later Columbia Pike).

After operating independently for years, in 1936 the Arlington County Library Association was formed, and the following year Libraries became an official County department with a budget that included an allocation of funds for the hiring of a library director.

From their founding, these branches only provided services to white constituents.

Libraries in Other Municipalities

The neighboring jurisdictions around Arlington were similarly segregated during the Jim Crow era, and followed a similar pattern of segregated volunteer-led branches that incorporated into segregated municipal systems. From the 1930s-1960s, libraries became an increasingly significant issue in the fight for equal access to public services, in both the state and the nation. In some places, it took decades to achieve integrated facilities.

In one notable local case, in August 1939, a group of Black Alexandrians held a sit-in at the Queen Street branch of the Alexandria City Public Library, protesting the denial of resources to Black members of the community. Police arrived and arrested the protesters for “disorderly conduct.” Samuel Wilbert Tucker (1913-1990), a lawyer who led the demonstration, was prepared to challenge the City in court, but the City stalled negotiations in an effort to resist integration.

Against Tucker’s wishes for integration, the City instead built a segregated library for Black patrons, which would remain the only option available to Black Alexandria residents until desegregation in the 1960s. The Robert H. Robinson Library was incorporated into the Alexandria system less than a year after the sit-ins under the “separate but equal” segregationist doctrine.

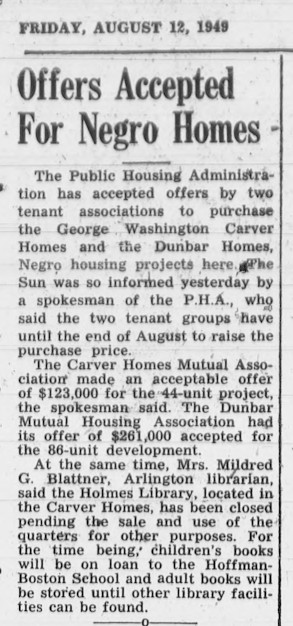

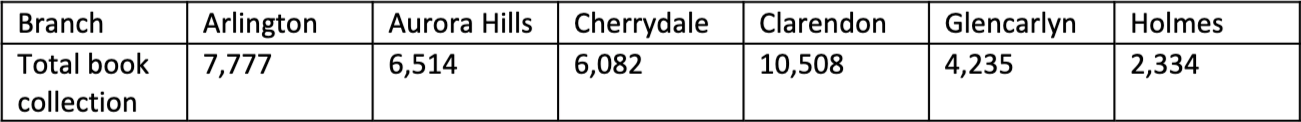

At this time, the only library available in Arlington to Black children was the school library at Hoffman-Boston School, which operated as the only secondary school for Black students until the public school system desegregated in 1959.

Students study in the Hoffman-Boston School

library, circa 1950. Image from RG 307.

An Association to Organize the Library

Facing this lack of local and accessible resources, a group of Black Arlington residents, without financial assistance from the County, came together to establish the Henry Louis Holmes Library Association in July 1940, to maintain a library for use by the Black community. Since this library would serve Black residents across the County, representatives from organizations across Arlington were also called to join in in the efforts. Early members represented the Civic Association of Halls Hill, the Nauck neighborhood and the Jennie Dean Club.

A Board of Directors was also assembled, including the Reverend A. Mackley (representing Mount Olive Baptist Church), Mrs. Henry Chapman, Mrs. Jessie Pollard, Mrs. Annie Belcher, and Mrs. Nora Drew (Mrs. Drew was the matriarch of the Drew family and mother of Charles Drew, a pioneering surgeon and founder of the modern-day blood bank. Her daughter, Nora Drew Gregory, later became a well-known library advocate as a library board trustee for Washington, D.C.).

The group then selected officers and committees, including the Constitution; Name; Books; Accessioning and Cataloging; Program; Ways and Means; Publicity; and Rooms committees. Selected as its first president was Kitty Bruce, with Marie Ponce serving as secretary. Kitty Bruce was chairwoman of the Arlington Inter-Racial Commission and a teacher at the Francis Junior High School in Washington, D.C., a school for Black children living in the Foggy Bottom and Georgetown neighborhoods.

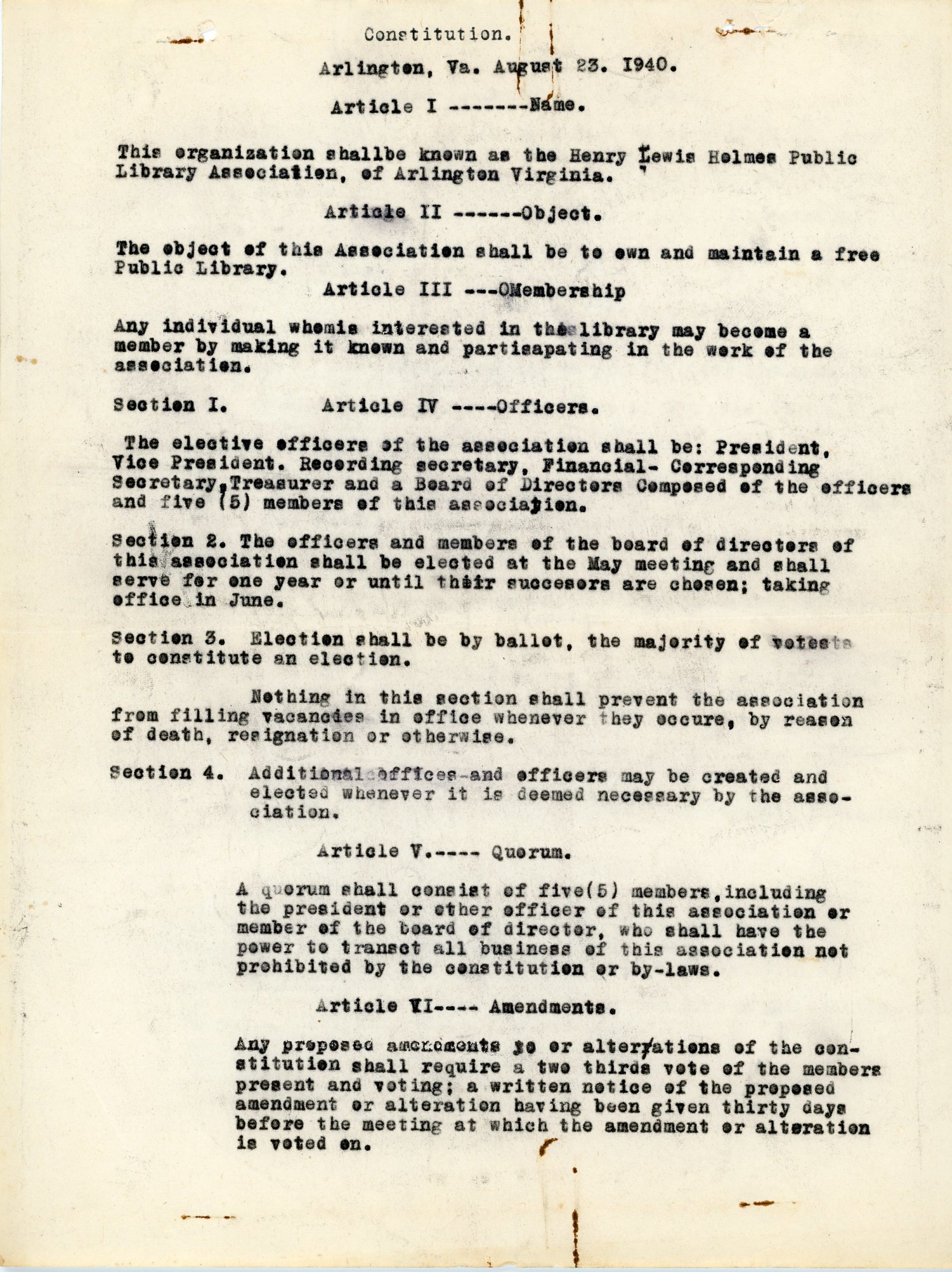

The first page of the Holmes Library Association Constitution. It is notable that the library association, while formed with the intention of serving the Black community, wrote that “Any individual who is interested in the library may become a member by making it known and participating in the work of the association.”

Honoring the Past

In August 1940, the Library Association voted to honor Henry Louis Holmes in both its name and the name of its forthcoming branch. Holmes had been a prominent local civic leader, serving as the elected Commissioner of Revenue for Alexandria from 1877 to 1904. Previously enslaved, Holmes had come to Freedman’s Village in Arlington in his early life. He gained political success in the Reconstruction-era boom of Black political leaders, and was involved with the Radical Republican party, as well as in fraternal organizations such as the Masons and Odd Fellows and as a trustee of St. John’s Baptist Church. He also founded the Butler-Holmes community, a Black streetcar neighborhood in what is now the Penrose neighborhood.

In making this decision, the Association sought the blessing of Mrs. Emma Clifford, Holmes’ daughter, for use of the name. Mrs. Clifford wholeheartedly approved of the naming decision and donated a portrait of Mr. Holmes to the library as well as a set of encyclopedias.

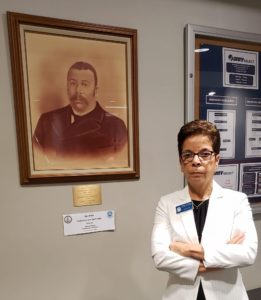

Left: Portrait of Henry L. Holmes, date and artist unknown. Image courtesy of the “Built By the People Themselves” digital exhibit.

Right: The portrait of Holmes is currently located in the offices of the Commissioner of Revenue on the second floor of the Bozman Government Building. It was donated in 1985 by the Arlington Links Club, which described it as having once hung in the original Holmes library building. Former Commissioner of Revenue Ingrid Morroy, elected in November 2003, was the second person of color since Holmes to hold the position in the history of the office. Image courtesy of Susan T. Anderson, Communications Director for the Commissioner of Revenue.

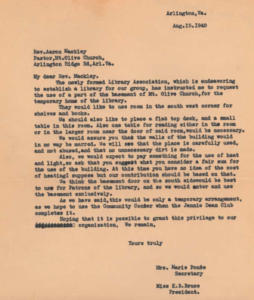

In August 1940, the library formally requested to be housed in the basement of Mount Olive Baptist Church, which was located at 700 South Arlington Ridge Road between Columbia Pike and Washington Boulevard in the Johnson’s Hill/Arlington View neighborhood.

This site was recognized as a temporary location for the library, which was expected to grow in the years to come. By September, the church had formally granted their request in turn, with a few stipulations regarding maintenance and upkeep. For one, the church would not charge the library rent, but asked for an occasional donation for things like the custodian’s salary and fuel.

Finding a Home for the New Library

The library initially supplied its catalog with donated books, which came from organizations such as the Alpha Gamma and Iota Chi Lambda sororities, and book showers hosted by other local civic groups. It was also noted that some books and shelves were donated from the Clarendon Library Association, as initiated by the Association's president Mrs. H.S. Cowman and a Mrs. Rice.

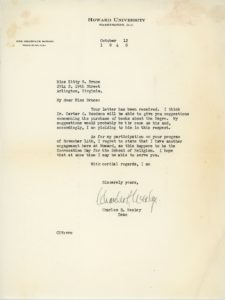

In addition, members of the association wrote letters seeking book recommendations from the historian and scholar Charles H. Wesley – the then-dean of the Howard University Graduate School – and Carter G. Woodson, the renowned Washington-D.C.-based historian, and the founder of Black History Month.

Opening Ceremony

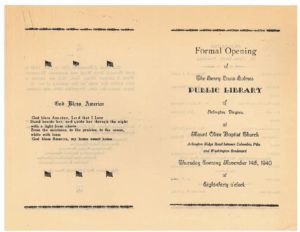

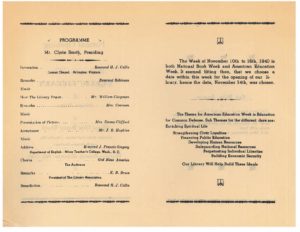

The Henry Louis Holmes Library formally opened on November 14, 1940, a date chosen to align with both National Book Week and National Education Week (Opening program 1 and 2).

Among the festivities marking its debut was a speech by the Rev. Dr. J. Francis Gregory, member of the department of English at the Miner Teachers College (Dr. Gregory’s grandson Francis A. Gregory would become the first Black member of the Washington, D.C., library board of trustees, and was the husband of Nora Drew Gregory. He is the namesake of the Francis A. Gregory Neighborhood Library in Washington, D.C.) Dr. Gregory addressed the crowd and delivered a speech, during which he stated: “The library in any community should be a center of activity in any community, serving as a social, cultural, ethical and spiritual, as well as intellectual, recreational center.” (The Formal Opening of the Henry Louis Holmes Library-1). He also gifted the library a copy of “The Life of Frederick Douglass,” a biography on the famous orator and abolitionist written by his father, James Monroe Gregory.

Program from the Holmes Library opening at Mt. Olive Church on November 14, 1940.

Another Home for the Holmes

The library was based in the Mount Olive Church basement until 1942, when the church property was taken over by the U.S. government. The church was ordered by the War Department to vacate the property in July 1942 , to make way for roadways leading to the Pentagon’s facilities. The church reopened at a new site at 1600 14th Street South in the Johnson’s Hill/Arlington View neighborhood in 1944.

In the meantime, the Holmes Library Association ran programs to benefit the community, including prominent speakers from the broader D.C. community. These included an address by Dr. Rayford Logan, a renowned Black historian, scholar, and professor emeritus at Howard University.

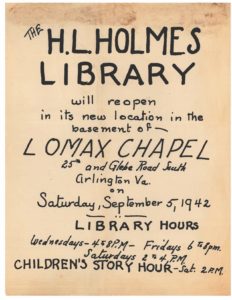

The Holmes Library found its next home in the basement of Lomax A.M.E. Zion Church, where it reopened on September 5, 1942. The Lomax site brought with it new developments, such as a children’s story hour.

Left: Flyer advertising the debut of the Holmes Library in the basement of Lomax church, its second home after Mount Olive.

Right: Lomax A.M.E. Zion at 2706 South 24th Street, taken August 31, 1996.

The Holmes Branch Incorporates into the County

Since founding the Holmes Library Association, the group had discussed joining with the County library system at a future date. In its initial meetings in July 1940, early long-term plans included eventually seeking financial assistance from the County. The first step in this was meeting County requirements via the American Library Association, which required 1,500 books to qualify as an official library. In its July 25, 1940, meeting minutes, Secretary Marie Ponce wrote: “It is hoped that from this beginning we can eventually work up the 1,500 books required before we can be recognized by the Library association.”

In February 1941 it was reiterated that the group would attempt to seek County aid (rather than state aid), and a Study and Plan Committee was formed to “carefully study out a plan to get aid from the County.” Plans around seeking County aid were always in the context of maintaining the Holmes Library separately, rather than as part of an effort to integrate the County library system.

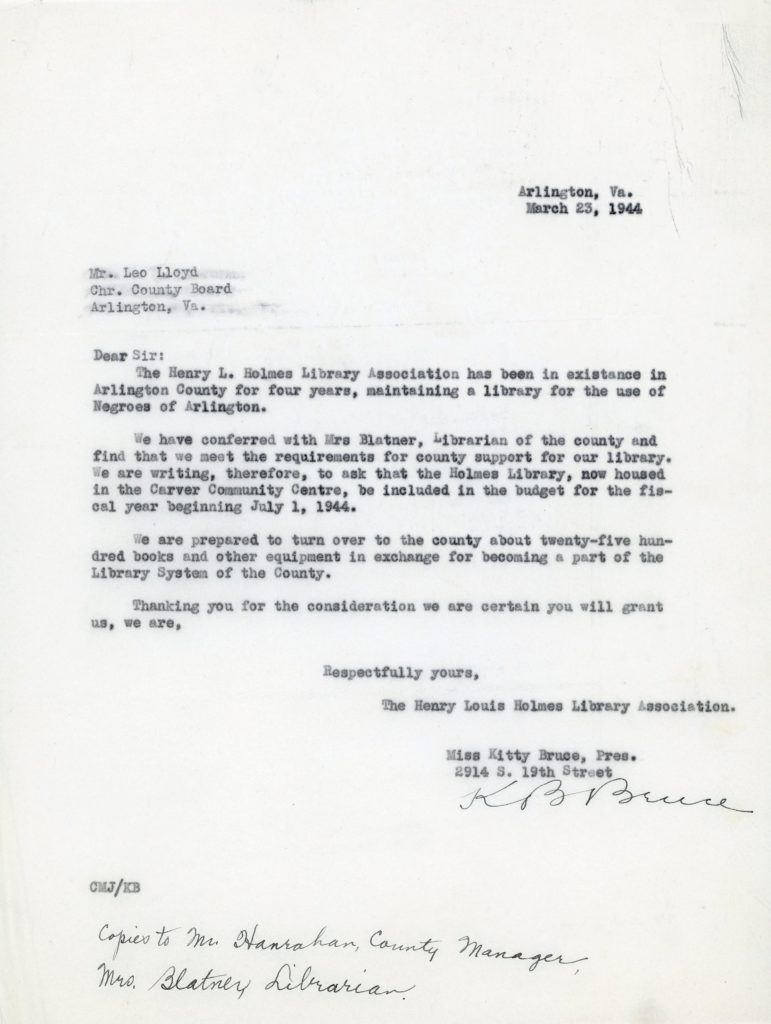

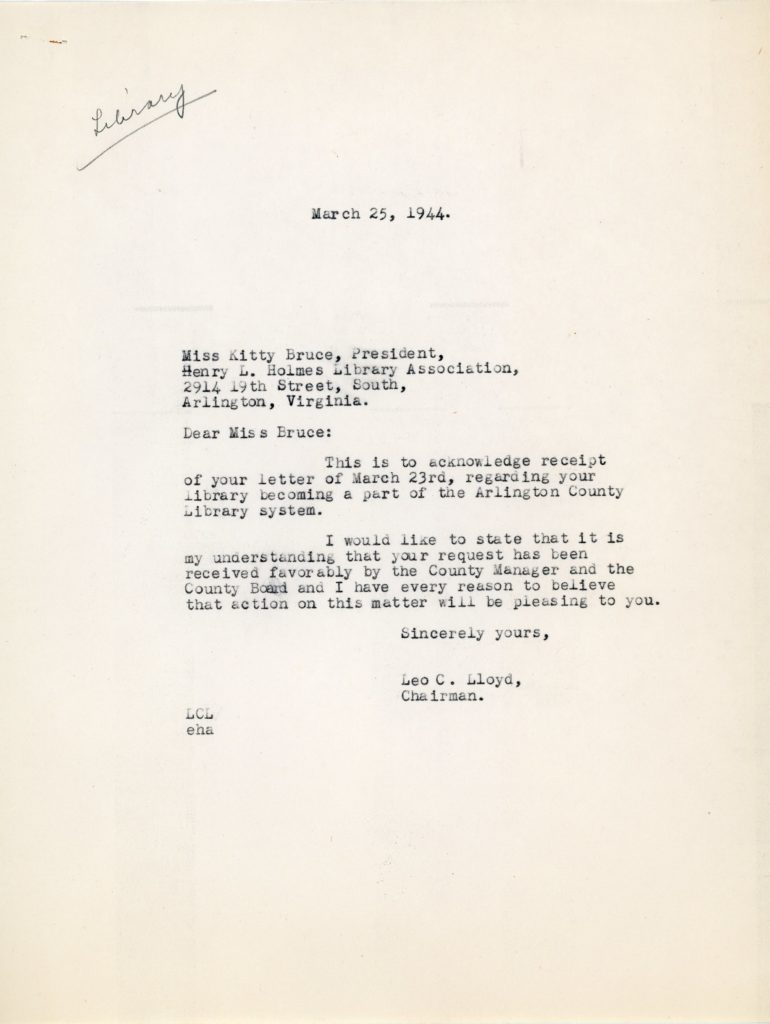

In February 1944, members of the Holmes Library Association met with Mildred Blattner, the County Librarian. By this point, the Holmes Library had surpassed the American Library Association’s requirement of 1,500 books, and offered to turn over its collection of 2,500 books to the County. In March 23 letters to County Board Chair Leo Lloyd and County Manager Frank Hanrahan, the Holmes Association asked to be included in the July 1944 County library budget. On March 25, Lloyd replied that their request had been received favorably, and on April 5, 1944, Holmes Library Association President Kitty Bruce appeared before the County Board to formally appeal for inclusion of the Holmes as a County branch.

Letters exchanged between Kitty Bruce and Leo Lloyd in March 1944

signal the incorporation of the Holmes Library into the County Library system.

Bruce and the Holmes Library Association were successful. The Holmes Library – now the Holmes Branch – was eventually bequeathed $2,100 from the County Board to open its new branch location, which would formally be a part of the County library system. This site would be the library’s first independent and freestanding building. The County also established a deposit station in the Hoffman-Boston School library in 1945.

Holmes’ Home in the Carver Homes

The Holmes Branch’s final location was in an administrative building in the George Washington Carver Homes complex at 13th Street South and South Queen Streets. The Carver Homes had begun as a Federal Public Housing Authority project in 1943 to house displaced families and individuals largely from East Arlington and Queen City whose homes had been razed during the construction of the Pentagon. By 1944, the housing complex consisted of 270 trailers and 100 temporary public-financed housing units. The same year, after a visit from first lady Eleanor Roosevelt, the government commissioned the George Washington Carver Homes, a permanent, 8-building apartment complex in Arlington View. This, along with the Dunbar Homes, a similar permanent housing complex, was completed in 1944.

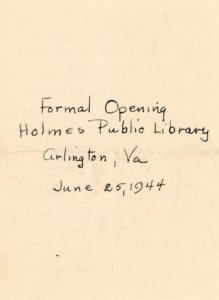

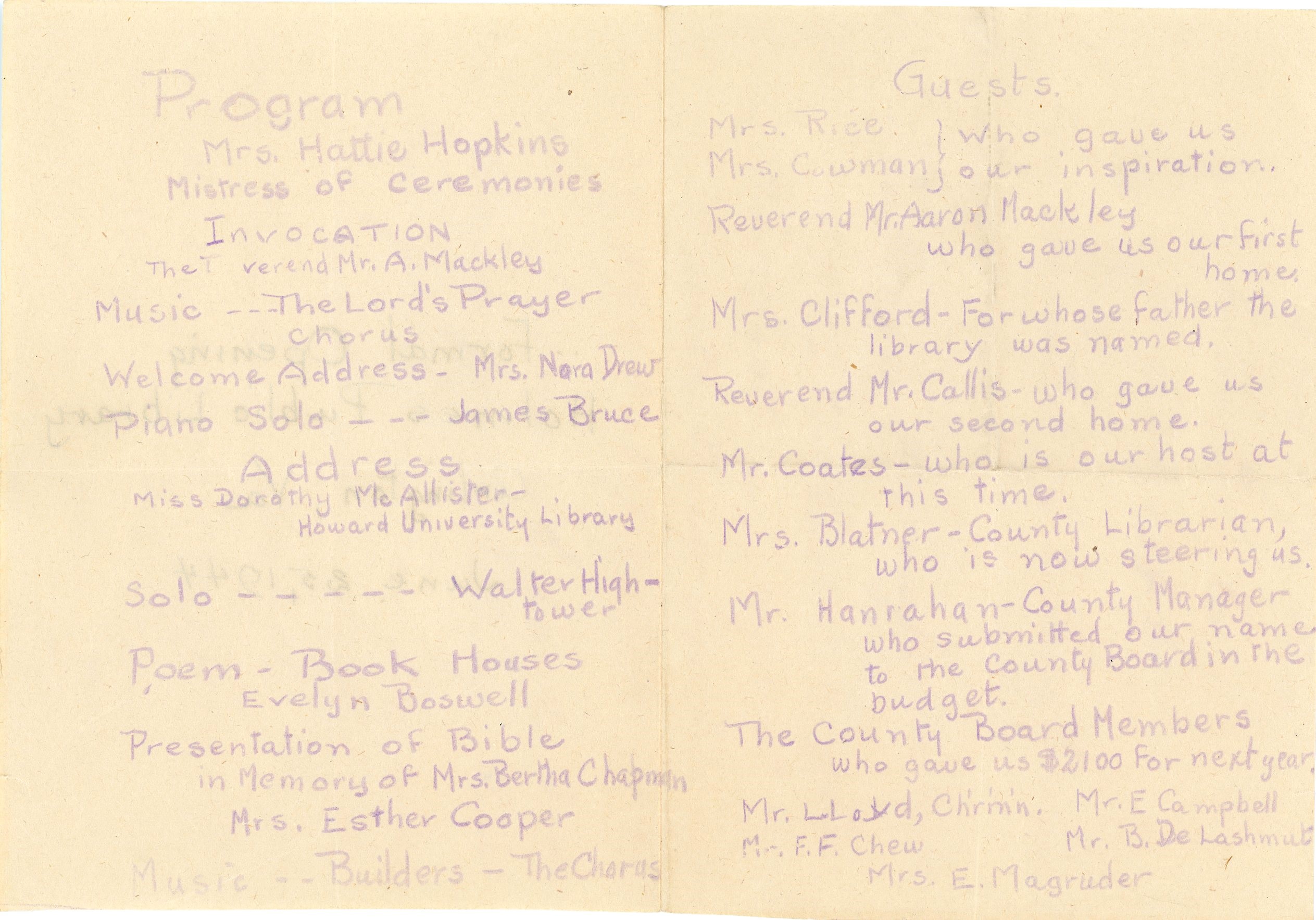

The Holmes Branch opened on the Carver Homes land on June 25, 1944, and was led by branch assistant Constance (Connie) Spencer. The occasion was marked by a robust celebration, featuring a speech by longtime association member Nora Drew, and an address by Howard University Library’s Dorothy McAllister. Branch librarian Madge Sydnor and branch assistant Rosaline Brooks joined the staff the following year.

Program from the June 25, 1944, opening of the Holmes Library.

At this point, the activities of the Holmes Library Association largely slowed, as their efforts in fundraising and staffing the library were absorbed by the County. Upon absorbing the Holmes collections into the wider County system, about 1,200 volumes were discarded after being labeled as not meeting branch standards, and 250 books were added from books gifted to the County and other copies.

In some ways, while County aid expanded the scope of the Holmes Library, inequalities and still persisted in how the County operated the branch. In an initial letter from Mildred Blattner to County Manager Frank Hanrahan, she wrote that “Since the reading habits of the colored population are not established I think it advisable to go rather slowly, providing popular books for the adult and standards for the children, until we can create reading habits that warrant a wider scope.”

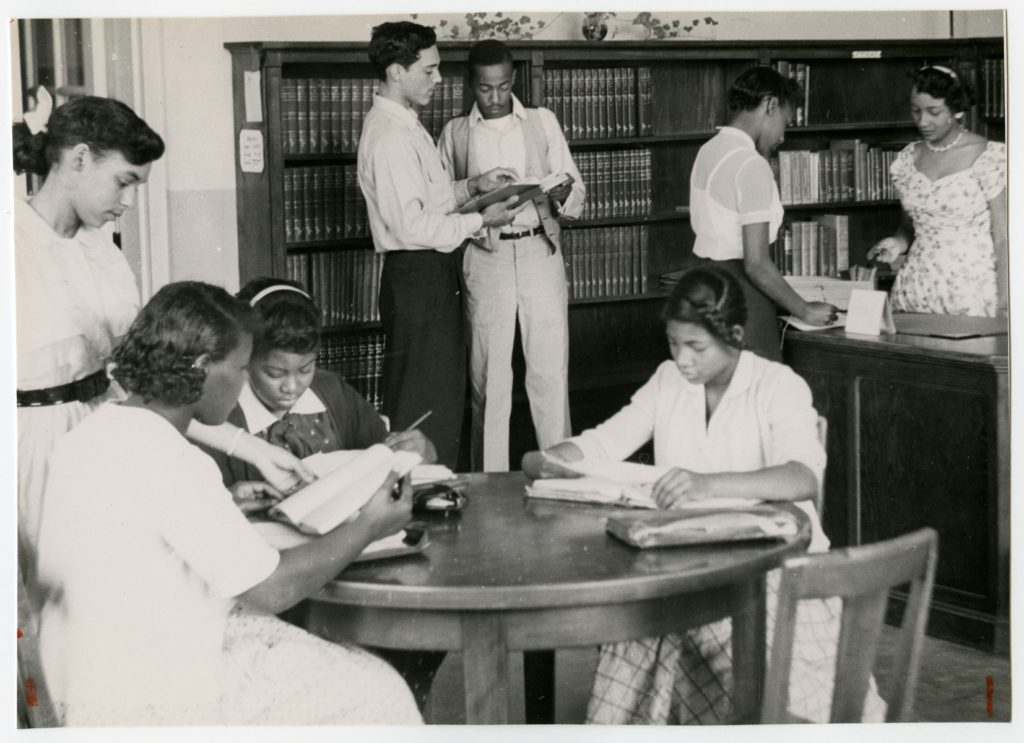

In some of the earliest aggregate circulation statistics between the branches in annual reports, the Holmes Branch consistently had the lowest number of total books. In the 1946-1947 annual reports, the Holmes had about half of the collection of the next lowest-stocked branch, Glencarlyn. From 1948-1949, only 113 additions were made to the Holmes’ collection, while the other branches received additions of anywhere between 500-1,482 books.

1946-1947 Total Book Collection:

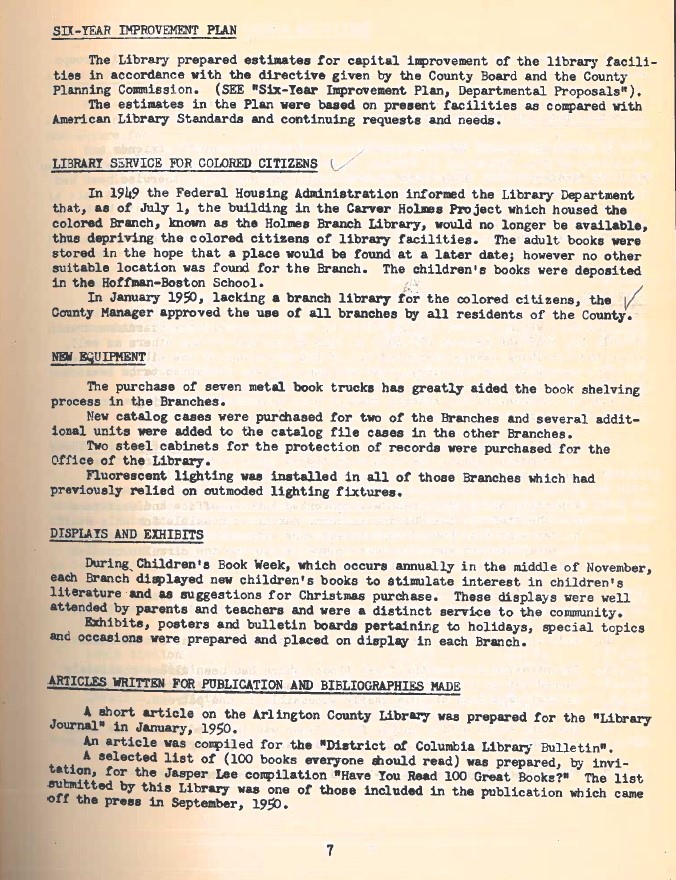

Forced Closure

The Holmes Branch remained open until 1949, when the branch was shuttered along with the sale of the Carver Homes property. After the end of World War II, Congress directed the Public Housing Authority to dispose of the Carver Homes and the Dunbar Homes. The properties were offered to the County for sale, which initially rejected the offers. In response, Black residents founded two cooperatives to purchase the former wartime housing - the Paul Lawrence Dunbar and George Washing Carver Mutual Associations.

The cooperatives’ bids were accepted, and the groups became the first two Black-owned cooperatives in the United States. The cooperatives sought to keep affordable housing options open, as other property developers could have excluded Black residents. Restrictive covenants and other segregated housing laws made purchasing homes and property exceedingly difficult for Black Arlingtonians, along with a general lack of available affordable housing.

Unfortunately, this housing victory came at the expense of the Holmes Branch. In July 1949, in a letter to County Manager A.T. Lundberg, the general housing manager of the Carver Homes reported that the library building was to be demolished to make room for further development.

In response, the Holmes Library Association reactivated in an attempt to save the branch. Mildred Blattner, who had corresponded with the housing manager and the Association, had suggested that continuation of the branch would be possible if a suitable new location was found. The Association swiftly located a new site, near the John H. Langston School, of which the group wrote “we feel that a branch would meet with the enthusiastic response of people in the area.” However, this option never came to fruition.

The children’s book collections – amounting to about 2,000 books – of the Holmes Library were subsequently moved to the library at the Hoffman-Boston School, where they continued to be circulated as public library holdings until 1960. At this point, the 1,617 volumes were likely absorbed by the Hoffman-Boston library, which continued to operate until its final class graduated in 1964.

In library reports, the only staff member listed for Hoffman-Boston was a “Custodian” whose name was not given and was referred to as a “Teacher at the School.” However, Hoffman-Boston in fact had a longtime school librarian whose name was Mildred Johnson.

The rest of the books from the Holmes collection were put into a storage shed behind the Clarendon Branch and used on occasion to replace copies or books or as duplicates if needed in the main library system.

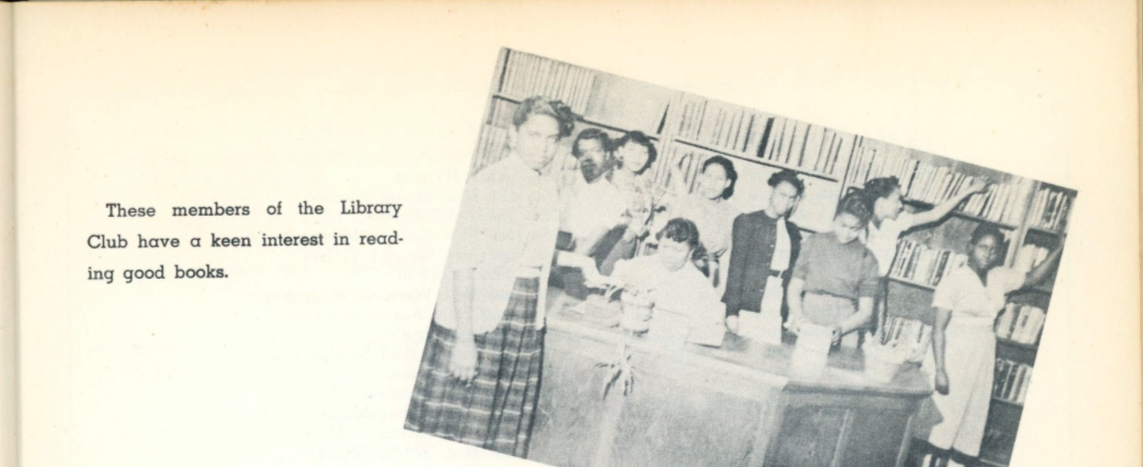

A Quiet Desegregation

In 1950, Arlington quietly reported that it had desegregated its libraries following the 1949 closure of the Holmes branch. The first mention of desegregation appears in the Library Department Annual Report for 1949-1950. Under the heading “Library Service for Colored Citizens,” it reported “In January 1950, lacking a branch library for the colored citizens, the County Manager approved the use of all branches by all residents of the County.” This was also listed as the date of desegregation in a 1964 report from the Community Council for Social Progress, and mention of library service for colored citizens does not appear in any subsequent annual reports, beyond mention of circulation statistics for the Hoffman-Boston library deposit station.

While Arlington’s libraries reported themselves as being open to all residents in 1950, the precise catalyst for desegregation is unclear. Beyond the pragmatic and economic implications of the branch’s closure, this decision may have also been influenced by a 1946 law passed within the Virginia Code, as Chapter 170 of the Laws of Assembly, requiring that libraries receiving state aid would serve all residents. Many library systems used this language to interpret separate but equal services permissible under this stipulation, as Arlington also had done within its system. Previously, the law surrounding libraries had stipulated that “The service of books in County library systems receiving state aid shall be free and given to all parts of the county, region, city or town.” This added specificity in the 1946 law may have prompted the library to integrate rather than continue to maintain separate facilities for Black residents.

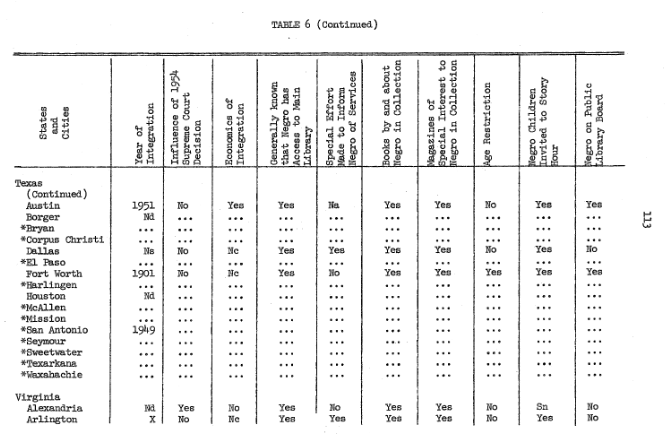

The timeline of desegregation has also been historically misreported in library accounts. Research initiated by the Fairfax County Public Library's Virginia Room found that in a 1963 unpublished thesis titled "Integration in Public Library Service in Thirteen Southern States," written by Bernice Lloyd Bell, surveys were sent out to municipal branches across the South regarding desegregation progress. In its response, Arlington indicated that “the library has always been open to all races.” The survey respondent (who is unknown) also suggested that neither the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision nor economic factors influenced the decision to integrate.

Survey results from Bernice Lloyd Bell’s unpublished 1963 thesis “Integration in Public Library Service in Thirteen Southern States.”

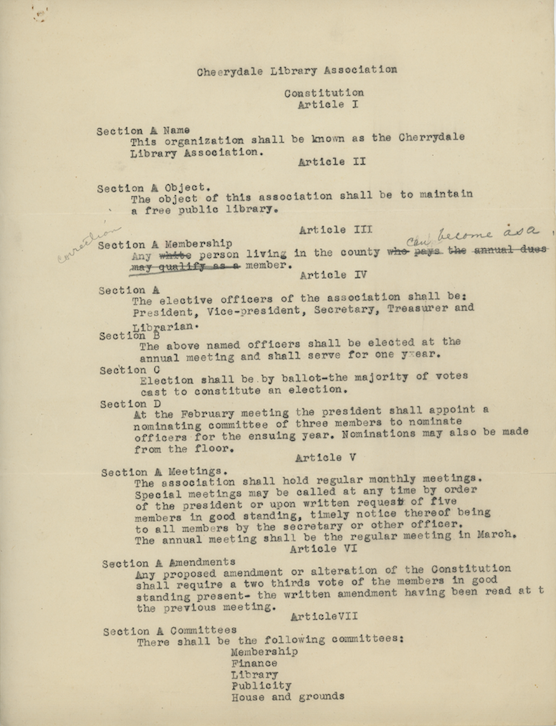

While the 1954 Brown vs. Board response aligns with the timeline of the 1950 decision, the statement that the libraries had “always” been open to all residents was not true. This response was directly contradictory to another survey completed in 1944-1945 by Mildred Blattner for a Virginia State Library report, in which she acknowledges that service to Black residents was only available at a designated branch, not in the main library. Additionally, an undated constitution from the Cherrydale Library Association, a section was amended to change its wording on membership from “Any white person living in the county who pays the annual dues may qualify as a member” to “Any person living in the county can become as a [sic] member.” This change may have reflected the 1950 County desegregation policy, and signals that the library had clearly not always served all residents.

Cherrydale Library Association and Bylaws, no date. From RG 29.

An Unclear Reality of Desegregation

It is also unclear the degree to which desegregation became publicized, or how Black residents came to use the integrated facilities. No local newspapers reported the desegregation, and though the 1963 survey reported that it was generally known that Black residents could access the main library, there is no quantitative evidence of this.

In a 1986 interview with local civil rights activist Dorothy Hamm, who came to Arlington in 1950, she suggested that at this time the libraries were still unavailable to Black residents, either by law or by the de facto practices of segregation.

Narrator: Dorothy M. Hamm

Interviewer: Edmund Campbell and Cas Cocklin

Date: February 21, 1986

Edmund Campbell: Dorothy, let's look at the conditions you found in Arlington in 1950 as far as the relationship between the races is concerned. Were there legal restrictions that were repugnant to members of the Black race at that time?

Dorothy Hamm: Yes, there were. At that time, the schools were segregated. The libraries did not permit Blacks.

EC: You mean you could not come in and get a book in the library?

DH: No, we did not, the children could not. In fact, we could not.

EC: You're speaking of the public library?

DH: As far as I can recall, the Arlington County Libraries were. The children obtained their information from the school libraries.

EC: Was there any way adult Blacks could obtain books from the library?

DH: I do not believe it was [possible] after so many years I cannot really say.

Continued Inequality Across the County

Even once the libraries had been reported as desegregated, rampant inequalities across the County made access to resources still more difficult for Black residents. In a 1959 speech delivered by an unknown speaker to the local Community Council for Social Progress, it notes that:

“[Black Arlingtonian] children have attended Arl[ington’s] separate and unequal colored schools. Near them is a meagerly equipped playground too small for a ball diamond. They are excluded from nearby white parks and playgrounds where there are ball fields and tennis courts. No Arlington movie will admit them and no Arl[ington] restaurant will serve them. They may use the Arl[ington] public libraries on an unsegregated basis. As the result of an NAACP suit segregation on busses serving Arl[ington] ended about ten years ago.”

So while Arlington’s libraries were eventually open to Black residents, it was in a larger context of a deeply segregated system in which the white majority of the County sought to prevent Black people from accessing resources. As referenced in the above speech, Arlington's public school system did not desegregate until 1959, following an extended legal and bureaucratic battle. The County's parks and recreation system did not desegregate until 1962, when the Negro Recreation Section, which had been designated for Black residents, was absorbed into the main County department.

No records have been found reflecting circulation statistics of Black residents in the integrated system, or how new patrons used the facilities. None of the affiliated librarians or volunteers at the Holmes Branch were later listed as being hired by or on the staff of the main County branches.

Conclusion

While the story of Arlington’s library desegregation is at times murky, the story of the resilience and dedication of the Holmes Library Association is undeniable. Faced with a persistent and systemic denial of resources, this group created a haven for books, learning, and discussion for members of their community at a time when the County would not do so.

This article is based on primary source documents found in the Community Archives at the Center for Local History. Documents regarding the Holmes Library can be found in Record Group 29.

This article was also heavily influenced by research conducted by Fairfax County Public Libraries regarding the desegregation of libraries across Northern Virginia. For a more in-depth look at how other library systems desegregated in Northern Virginia, see this report prepared by Fairfax County Public Libraries – Unequal Access: The Desegregation of Public Libraries in Virginia. FCPL also created a detailed video presentation on the topic, which is available on YouTube: Unequal Access: The Desegregation of Public Libraries in Virginia.

This article was authored by Camryn Bell, who is part of the County's management intern training program and has assisted in the collections of the Center for Local History since 2019.

We hope this article adds to the conversation about segregation in its many forms, and about the history of race in Arlington County more broadly.

And we want to know: How does this story relate to your story? Do you have memories about the Holmes Library, or about segregation in Arlington's library system? Use the form below to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields

![[Holmes Branch Library] Exterior of the Holmes branch of the Arlington Public Library system. 1946, 1 print, b&w, 8 x 10 in..](https://library.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/29-0046p6-scaled.jpg)

![[Interior of the Holmes Branch Library] A librarian and two children inside the Holmes Branch of the Arlington Public Library 1946, 1 print, b&w, 8 x 10 in..](https://library.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/29-0359p6-scaled.jpg)