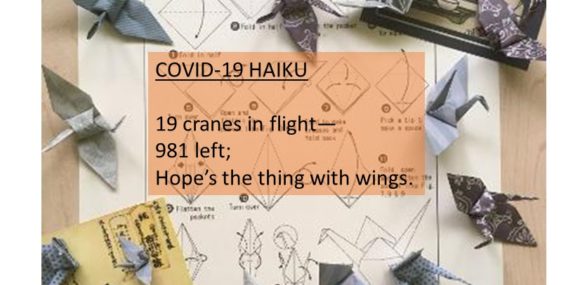

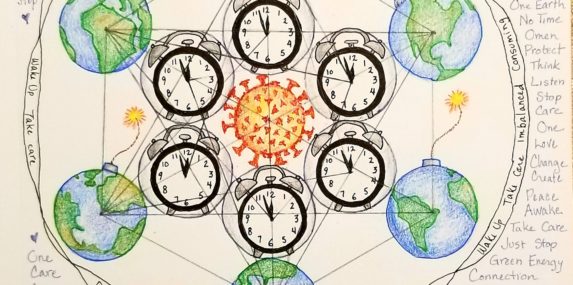

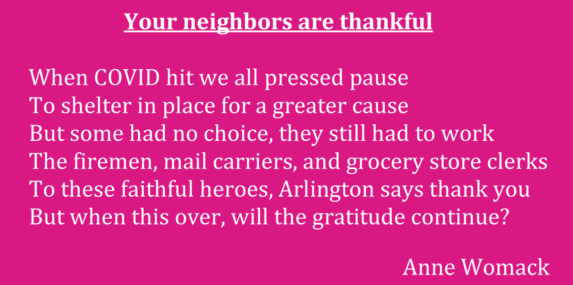

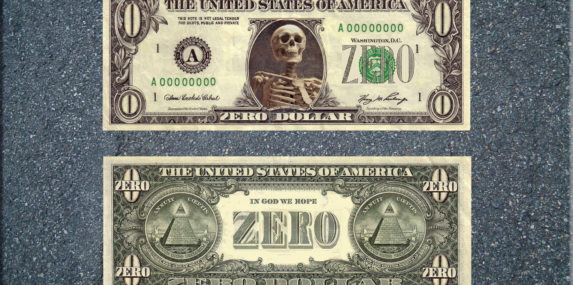

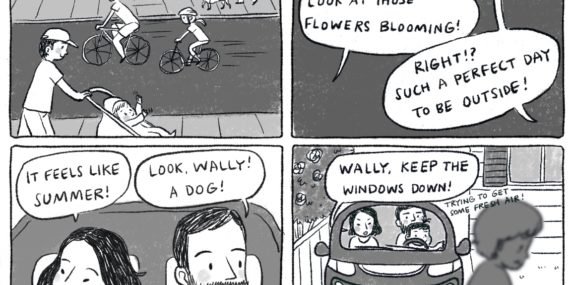

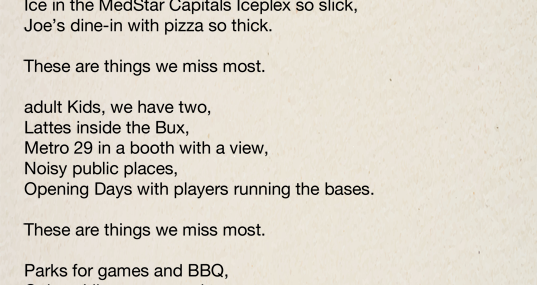

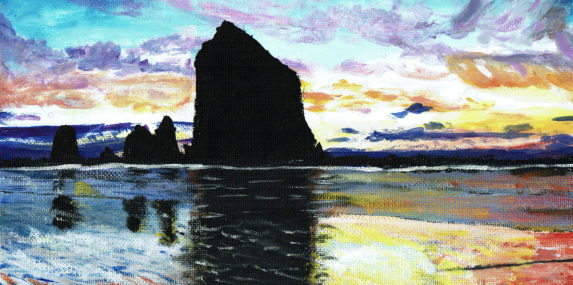

May 26: Keep Hope Alive

Quaranzine is a weekly collection of creative works from the Arlington community that documents how we responded to this strange time we find ourselves in. Submit your own work.

The next deadline for submissions to Quaranzine is Thursday, May 28