Did you wish you had attended Arlington Reads with George Saunders last week? You still can! Watch his amazing author talk on YouTube, available through November 4.

While the event with Barbara Kingsolver has a waitlist, you can still RSVP for Pulitzer Prize-winning author, Andrea Elliott on Nov. 17.

Thursday, Nov. 17, 6:00 - 7:30 p.m.

Central Library

Join us for a conversation between Pulitzer Prize-winning author Andrea Elliott, Library Director Diane Kresh, and Department of Human Services Director Anita Friedman to discuss Elliott's book "Invisible Child."

The conversation will be followed by audience Q&A and a book signing. Books will be available for purchase during the event, courtesy of One More Page Books.

The free event will be livestreamed for registered attendees. There will be no recordings after the event has concluded.

On Tuesday, One More Page Books will present a conversation between acclaimed author Barbara Kingsolver and Library Director Diane Kresh. The author will discuss her new book, "Demon Copperhead."

The event registration is full, but One More Page Books has a waitlist.

Click here to see all our titles by Barbara Kingsolver in our catalog.

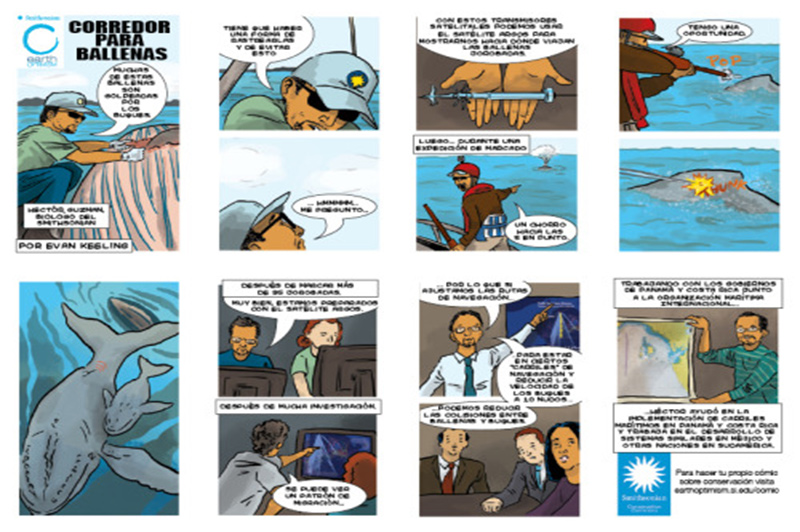

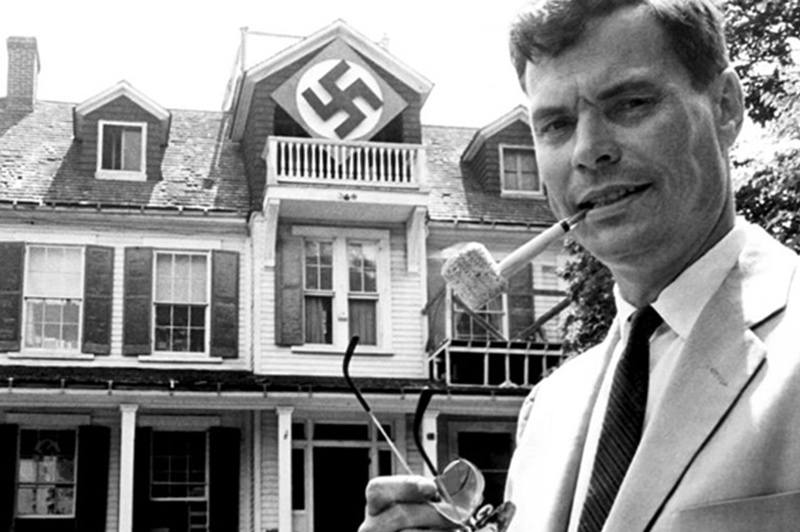

In 2023, we are looking forward to a new Arlington Reads season, "Get Graphic," featuring an incredible lineup of graphic novel authors: Alison Bechdel (Mar. 9), Jerry Craft (Apr. 27), Gene Luen Yang (May 4), Art Spiegelman (Sep. 21) and Liana Finck (Oct. 19). Stay tuned for more details coming soon!

Arlington Reads is made possible thanks to the generous support of the Friends of the Arlington Public Library.