"The time is always right to do the right thing." - Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

On August 28, the 48th anniversary of the "I Have a Dream" speech, the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Memorial will be formally dedicated in Washington D.C. Located in West Potomac Park and flanked by the Lincoln and Jefferson memorials, the addition of the King Memorial creates a monumental trifecta of leadership and inspiration.

As a child of nine in August of 1963, I had little knowledge of the man whose eloquence and personal courage undergirded a movement. I had no knowledge of the civil rights movement itself. African-Americans were just not a part of my everyday experience. Just as it is often observed that there are two Virginias, in 1963 there were two Arlingtons: the well-to-do, predominantly white North Arlington and the less prosperous, racially mixed South Arlington. It was a distinction that was more than just directional. There were few students of color in my elementary school, Stewart-Tuckahoe, when I attended from 1960-1966--a fact consistent with the 1960 Census, which reported only 7,063 foreign–born persons or 4.3 percent of the County’s total population.

High View Park in North Arlington and Arlington View and Green Valley (Nauck) in South Arlington were all that remained of the County’s African-American communities. High View Park, known in my day as "Hall's Hill," was a neighborhood not far from where I grew up. It epitomized the less prosperous and segregated Arlington: an enclave of substandard housing and dead-ended, unpaved streets that for much of its history had been literally walled from the white neighborhoods it bordered by a series of 7-foot fences.

The year of King’s speech, the Arlington Planning Commission established a committee to study how best to maintain residential neighborhoods, a study that led to the creation of the Neighborhood Conservation Program. On Feb. 13, 1965, the County Board approved a Neighborhood Conservation Plan for High View Park hailing the tireless efforts of the residents who spoke up for their neighborhood’s civic rights. Abraham Lincoln, whose 156th birthday was celebrated the day before, would have been proud.

As significant as this moment was in Arlington's pursuit of racial parity, it was but the latest example of the County’s black and white residents working together for common cause. A few years earlier, some of the High View Park champions--E. Leslie and Dorothy Hamm and Peggy Deskins – had joined Edmund and Elizabeth Campbell and others to face down Sen. Harry Byrd’s "massive resistance" and integrate the County’s schools.

The Supreme Court's Brown v. Board of Education decision to end school segregation "with all deliberate speed" rocked Virginia to its core in May 1954. The "political museum piece" that was Virginia, as characterized by political scientist V.O Key in his classic, "Southern Politics in State and Nation" [1949], was stuck on the horns of a dilemma, caught between the moral imperative to do right by Virginia and remain segregated, or to do the right thing. It was an issue that pitted being a Virginian against being an American. Arlington, having evolved from a bedroom community in the shadow of the nation's capital to a thriving, socially progressive community of residents whose political views were markedly different from those of the rest of the state, found itself at the center of the fight.

By 1956, political passions were running high in Richmond as "massive resistance" to the High Court's mandate was gaining momentum, giving rise to a plan to prevent any integrated schools from receiving state funds and authorizing the governor to order any such school to close. Meanwhile the NAACP was filing lawsuits across the state to force integration, including a suit brought on behalf of 15 African American and white parents and 22 students in Arlington.

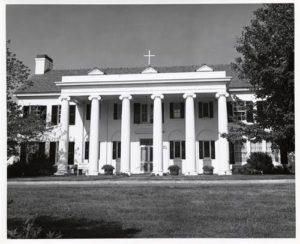

The case was named for Clarissa S. Thompson, an African American student who wanted to attend Arlington's all white Washington-Lee High School instead of the all black Hoffman-Boston. After hearing oral arguments, Alexandria Federal District Judge Albert V. Bryan, who only four years before in writing the opinion in the original Prince Edward County school integration case* stated that racial segregation caused no hurt or harm to either race, ordered that the schools in Arlington be desegregated. Suits and countersuits ensued--deliberation without speed.

Finally, on Jan. 19, 1959 (birthday of Virginia native son Robert E. Lee), the state’s Supreme Court of Appeals, by a ruling of 5-2, overturned the Virginia legislature's "massive resistance" laws and its threat of schools closures, declaring them in violation of the Virginia Constitution. The issue of school integration had assailed Virginia’s traditional political culture, a culture that was oligarchic, parsimonious, suspicious of "big" government, discouraging of public participation in the affairs of state, obeisant to the way things were. Throughout the long, slow march to integration in Virginia, rhetoric trumped reason; fear mongering triumphed over fairness; delay prevented "deliberate speed." Traditional Southern values were pitted against unwanted northern influence--ideologues against pragmatists.

The press, too played a powerful role on both sides of the integration issue. For every Richmond News Leader editorial that intrepidly egged on the resisters, editorials in both the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot and The Washington Post and Times Herald, penned by Lenoir Chambers and Robert Muse, respectively, eschewed moral turpitude and urged action and acceptance.

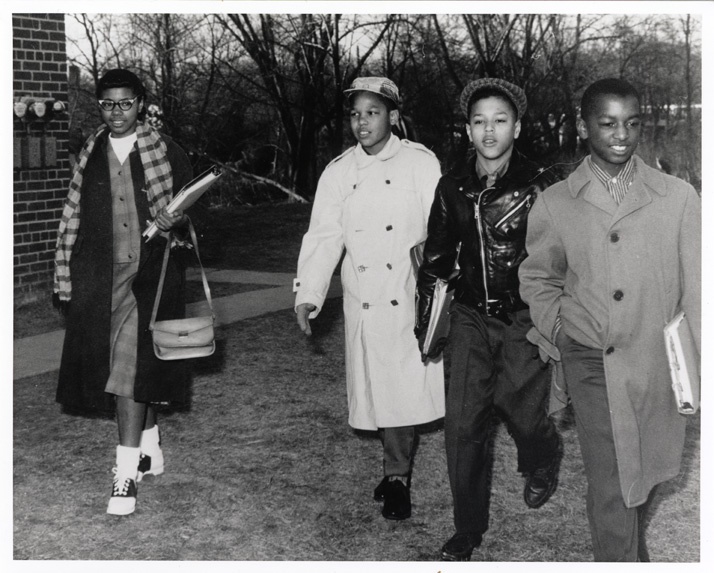

Virginia fought the law, but the law won. On Feb. 2, 1959, Ronald Deskins, Michael Jones, Lance Newman and Gloria Thompson (sister of Clarissa) entered Stratford Junior High School, splitting a phalanx of approximately 100 helmeted Arlington police officers who were Little Rock-ready with gas grenades, masks and batons. Their walk to school irrevocably changed Virginia although at the time, they were unaware of its historical significance.

Years later, reminiscing at a panel discussion with 500 students at Stratford Junior High (now H-B Woodlawn), the four understated their roles on that important day citing their parents and other community leaders – blacks and whites -- as the true heroes of Arlington’s integration story. The integration of Stratford was but the first of many small steps toward integration. It would still be years before black and white children could sit alongside one another at drug store counters and drink Cokes, attend dances together, or compete on the same sports teams.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

* Prince Edward County Public Schools chose to close rather than integrate and remained closed from 1959-1964. It was the only county system in the country to do so.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The material for this story came from the archives of the Arlington Public Library's Center for Local History. The attached bibliography will help interested readers learn more about these important events in Arlington’s history.

VA Room Oral Histories about Desegregation

- Series 3, no. 26 Edmund Campbell

- Series 3, no. 48 Dorothy Hamm

- Series 3, no. 110 Ray Reid

- Series 3, no. 112 John Robinson

- Series 3, no. 061 Theda Henle

DVD:

- It’s Just Me: The Integration of Arlington Public Schools, Arlington Educational Television, Arlington Public Schools, 2001 (also available in circulating collection)

Segregation/Integration Collections in the Arlington Community Archives

- RG 7: Arlington County Public Schools

- RG 7B: Hoffman-Boston High School Records

- RG 9: Records of Citizen’s Committee for School Improvement

- RG 18: Personal Papers of Barbara Marx

- RG 19: Personal Papers of Elizabeth Pfohl Campbell

- RG 69: Arlington County Public Schools: Desegregation Materials (copies culled from RG 7)

Vertical Files:

- 5 Folders containing clippings, articles, memos, reports, etc. relating to desegregation

Books:

- A Chink in the armor : The Black-led struggle for school desegregation in Arlington, Virginia and the end of massive resistance by James McGrath Morris

- The Federal role in school desegregation in selected Virginia districts; a report

- Integration of Arlington County Schools: my story by Dorothy M. Bigelow Hamm

- The moderates' dilemma: massive resistance to school desegregation in Virginia edited by Matthew D. Lassiter and Andrew B. Lewis

- Up on the hill: an oral history of the Halls Hill Neighborhood in Arlington County, Virginia High View Park Oral History Project

- High View Park Neighborhood Plan, Arlington County VA. Office of Planning

- The Woodlawn case: a chapter in suburban school integration by Dean Allard

Of the two Shreve family cemeteries in Arlington, the Southern-Shreve cemetery could possibly lay claim to having a more unique history. Located on the north side of Fairfax Drive, between North Frederick and North Harrison streets, the cemetery sat near the property of Richard and Frances (Redin) Southern. Richard Southern was a landscape architect and horticulturist, who became known for pioneering the use of the tomato as a food. It may seem hard to believe in these modern times, but prior to Southern’s efforts, the tomato was widely regarded as being poisonous and was only used for decorative purposes.

Of the two Shreve family cemeteries in Arlington, the Southern-Shreve cemetery could possibly lay claim to having a more unique history. Located on the north side of Fairfax Drive, between North Frederick and North Harrison streets, the cemetery sat near the property of Richard and Frances (Redin) Southern. Richard Southern was a landscape architect and horticulturist, who became known for pioneering the use of the tomato as a food. It may seem hard to believe in these modern times, but prior to Southern’s efforts, the tomato was widely regarded as being poisonous and was only used for decorative purposes.