July 16, 1862: Ida B. Wells is Born

Celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with stories about the people and events that led to the passage of women’s suffrage in the United States.

Ida B. Wells was an investigative journalist, activist, and suffragist who led an anti-lynching crusade in the United States in the 1890s. She was also one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Portrait of Ida B. Wells, circa 1893. Image courtesy of the National Park Service.

Early Life

Ida B. Wells was born into slavery on July 16, 1862, in Holly Springs, Mississippi, to James and Lizzie Wells. Following the conclusion of the Civil War, Wells’ parents became politically active as the country navigated Reconstruction. Ida's father, James, was a member of the Freedmen’s Aid Society, as well as one of the founders of Rust College in Holly Springs – one of 10 historically Black universities founded before 1868 that is still operating today. Encouraged to pursue her education, Ida later enrolled at Rust College but was ousted from her studies after a dispute with the university’s president.

Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

At only age 16, she lost both of her parents and her infant brother to a yellow fever epidemic that had decimated Holly Springs. Left with custody of her other siblings, Wells was able to convince a school administrator that she was 18, and began teaching to support her family. In 1882, she moved with her siblings to Memphis to live with an aunt, and there she continued to work as a teacher. She began classes at Fisk University in Nashville, where she would commute to by train. On one of these trips in May 1884, Wells – who had purchased a first-class ticket – was forced to move to a segregated car for African American passengers. Wells refused to move and was forced off of the train. Wells went on to sue the railroad and won a settlement in court.

Inspired by this incident, Wells pivoted her career toward writing about the topics of race and politics. Under the pseudonym “Iola,” Wells’ work was published in a number of Black-owned newspapers and periodicals. She also went on to hold shares of two newspapers: The Free Speech and Headlight, and Free Speech. All the while, she continued teaching in the segregated Memphis school system, of which she was also a vocal critic. Due to her vocal stance against segregation in the city and in the schools, as well as her criticism of the condition of schools, she was fired from her position.

People's Grocery Lynchings

In 1892, Wells’ journalistic focus took a turn. After the murder of a friend and two of his business associates at the hands of a lynch mob in Memphis, Wells began reporting on the epidemic of lynching in the South.

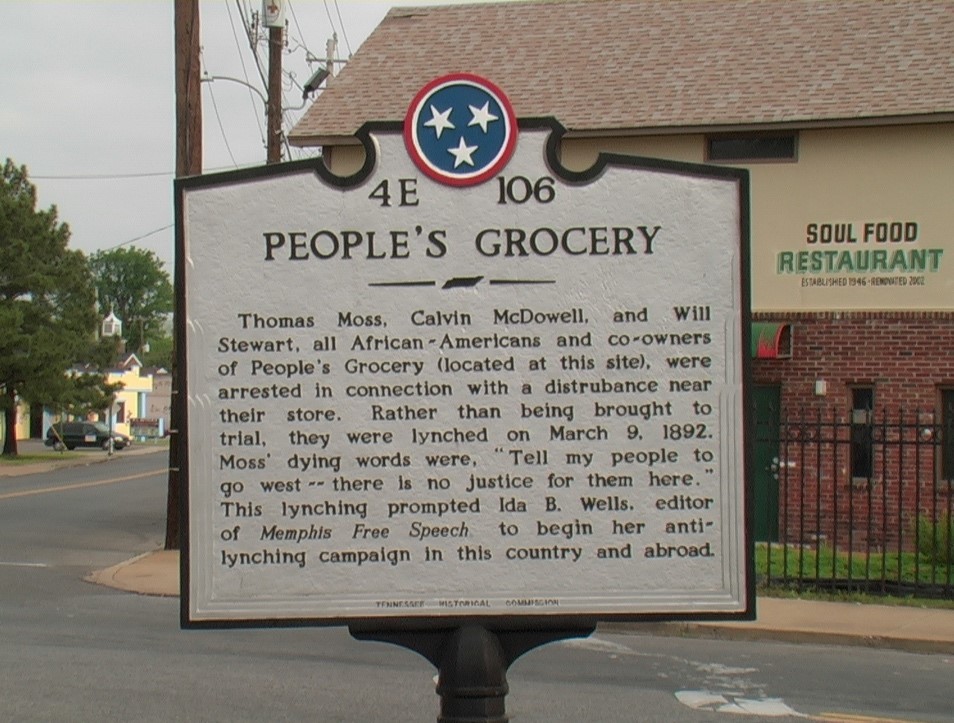

The three men, Thomas Moss, Calvin McDowell, and Will Stewart, had owned a storefront called People’s Grocery that was successfully competing with white businesses in the city. They were attacked and fought back, then were arrested, and subsequently dragged from jail by a white mob and lynched. This prompted Wells, who was also a godmother to Moss’ daughter, to write articles against lynching, and she frequently risked her own life to travel and learn more about killings that occurred in the region.

In 1898, she traveled to Washington, D.C., to present her anti-lynching campaign to then-president William McKinley.

A marker at the site of the 1892 People’s Grocery lynching. Image courtesy of the Lynching Sites Project, Memphis.

Wells faced violence herself over the course of her reporting – in response to one of her editorials, a white mob stormed her newspaper’s office and destroyed her property there. Wells was in New York at the time, but the incident led to her moving to Chicago, where she continued reporting on lynching for the New York Age; a newspaper helmed by T. Thomas Fortune, who had also been formerly enslaved. In 1892, she compiled her reporting on lynching into a book, titled “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.”

A report of the attack on Wells’ office in Memphis from the Washington Bee, June 11, 1892. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

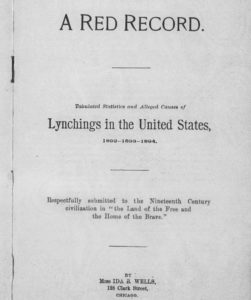

The front page of one of Wells’ books on lynching in the United States, published 1895. “A Red Record” was a follow-up to “Southern Horrors,” and included more statistics and case details. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The Alpha Suffrage Club

In addition to her reporting work, Wells was a founding member of numerous civil rights groups including the National Association of Colored Women and the Negro Fellowship League. She also attended the founding conference of what would later become known as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Wells’ work in advancing the suffrage cause was also prolific. In January 1913, she founded the Alpha Suffrage Club in Chicago, where she also served as president. The club aimed to promote city representatives who would best serve the Black community and who favored suffrage. The Alpha Suffrage Club was crucial in Illinois passing its Equal Suffrage Act on June 25, 1913, which granted women suffrage in the state.

As a result of their efforts, Wells and other members were invited to march in the 1913 Suffrage Parade in Washington, D.C. However, at the parade, Wells and the members of her group were asked to march at the back of the procession by the white parade organizers, to which Wells refused, joining in in the midst of the action.

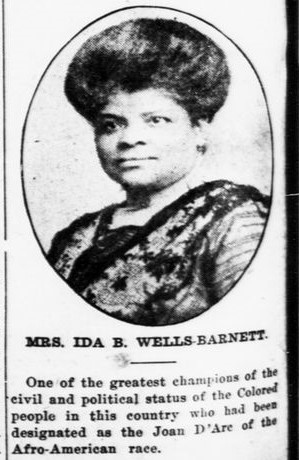

A profile of Ida B. Wells in Salt Lake City’s The Broad Ax, July 14, 1917. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Legacy

Wells died in 1931 but continued her career and life as an activist until the end of her life. In 1929 and 1930, she ran for state senator but was defeated – however, simply running as an African American was unprecedented at the time and her campaign was revolutionary in and of itself.

Wells’ legacy has long been overlooked in the scope of women’s suffrage, civil rights activism, and the progression of investigative reporting in the country. Just this year, she was posthumously awarded the Pulitzer Prize, “For her outstanding and courageous reporting on the horrific and vicious violence against African Americans during the era of lynching.” She is also among those featured in the New York Times’ “Overlooked” project, which highlights individuals who previously were not given the space for an obituary. You can read their retroactive obituary for Wells on their website.

A monument has also been proposed to honor Wells in her longtime home of Chicago.

Image courtesy of the League of Women Voters Chicago.

The Library has a number of resources to learn more about Ida B. Wells, as well as some of her original works:

By Ida B. Wells:

- Mob Rule in New Orleans: Robert Charles and His Fight to Death

- The Red Record

- Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases

- The Memphis Diary of Ida B. Wells

About Ida B. Wells:

- Ida: A Sword Among Lions, by Paula Giddings

- To Tell the Truth Freely: The Life of Ida B. Wells, by Mia Bay

2020 marked the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment.