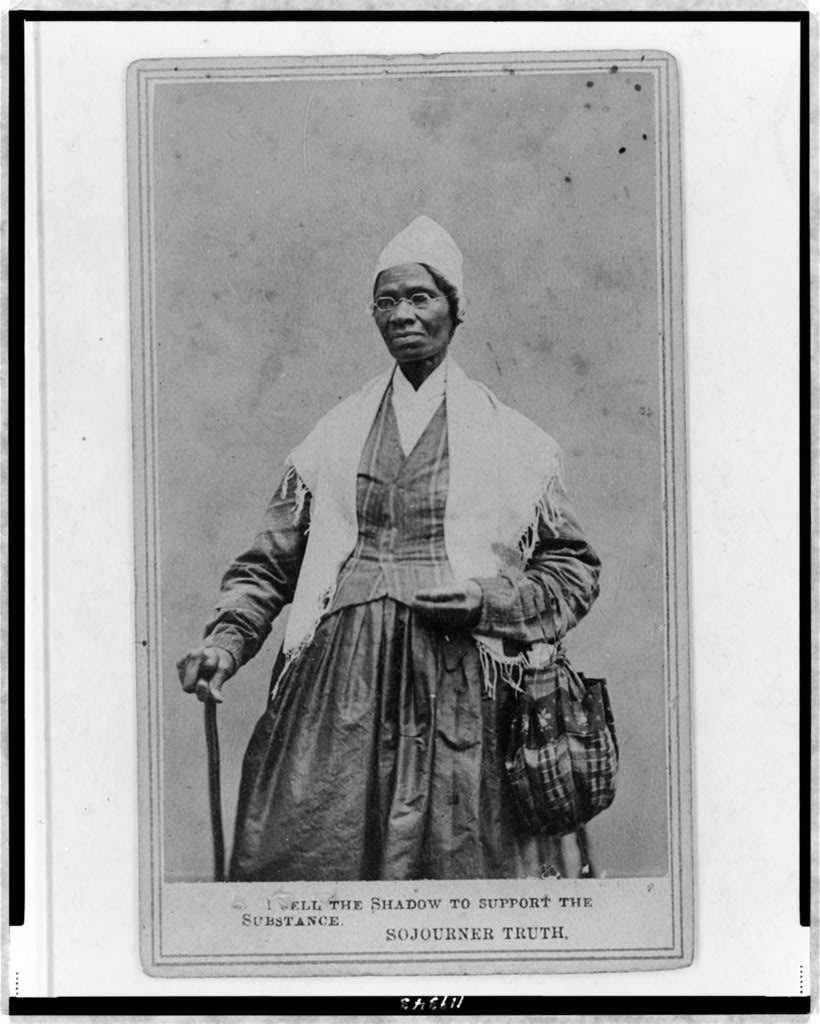

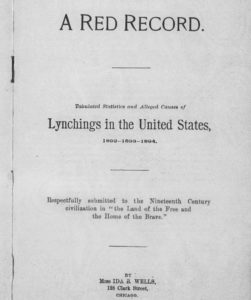

August 26, 1920: 19th Amendment is Adopted

Celebrate the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with stories about the people and events that led to the passage of women’s suffrage in the United States.

The 19th Amendment was officially adopted into the U.S. Constitution on August 26, 1920, marking another significant date on the journey to achieve universal suffrage.

“Unknown Photographer, ‘Women voting,’ circa 1925.” Image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

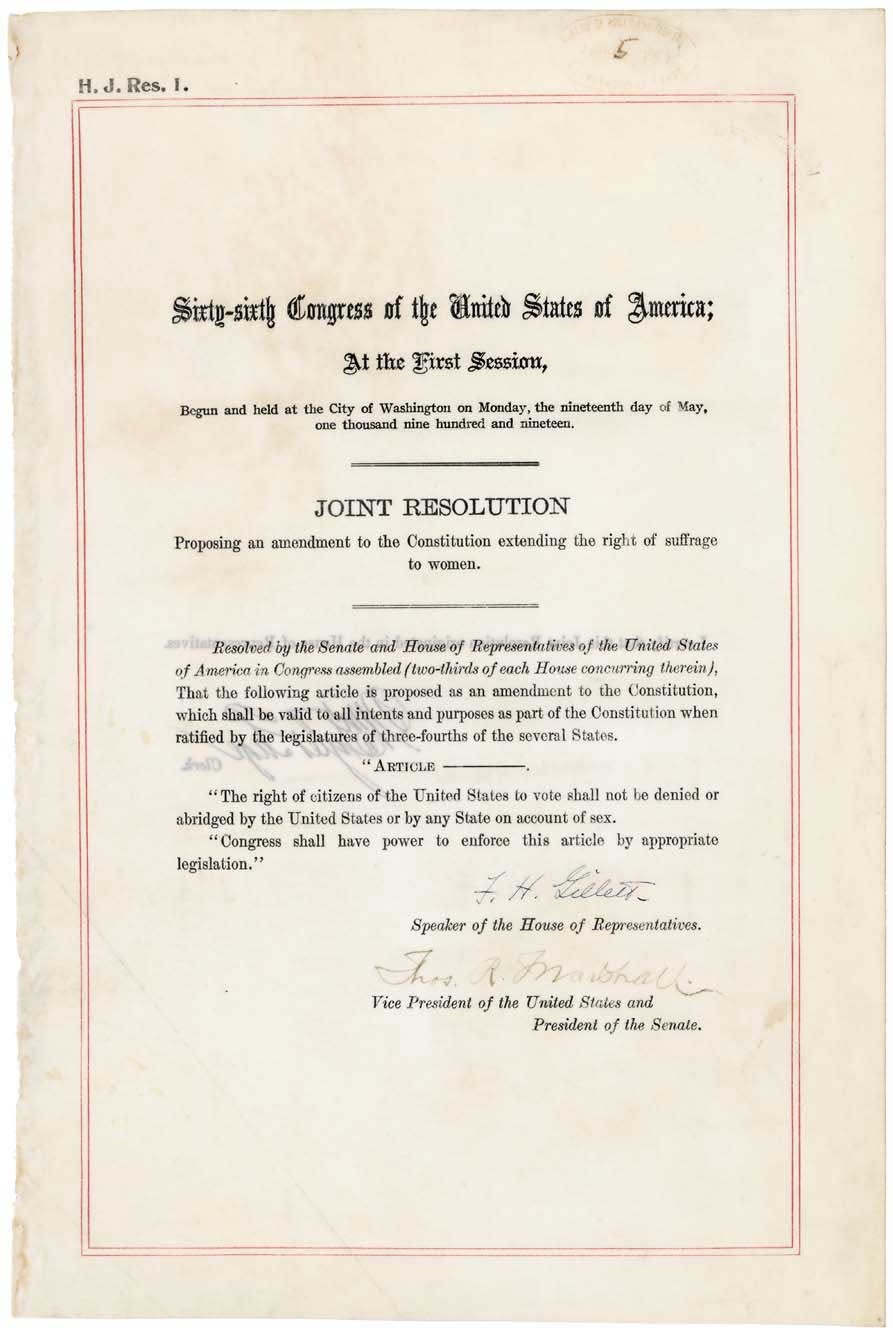

Consisting of two sections, the Amendment reads: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex” and “Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

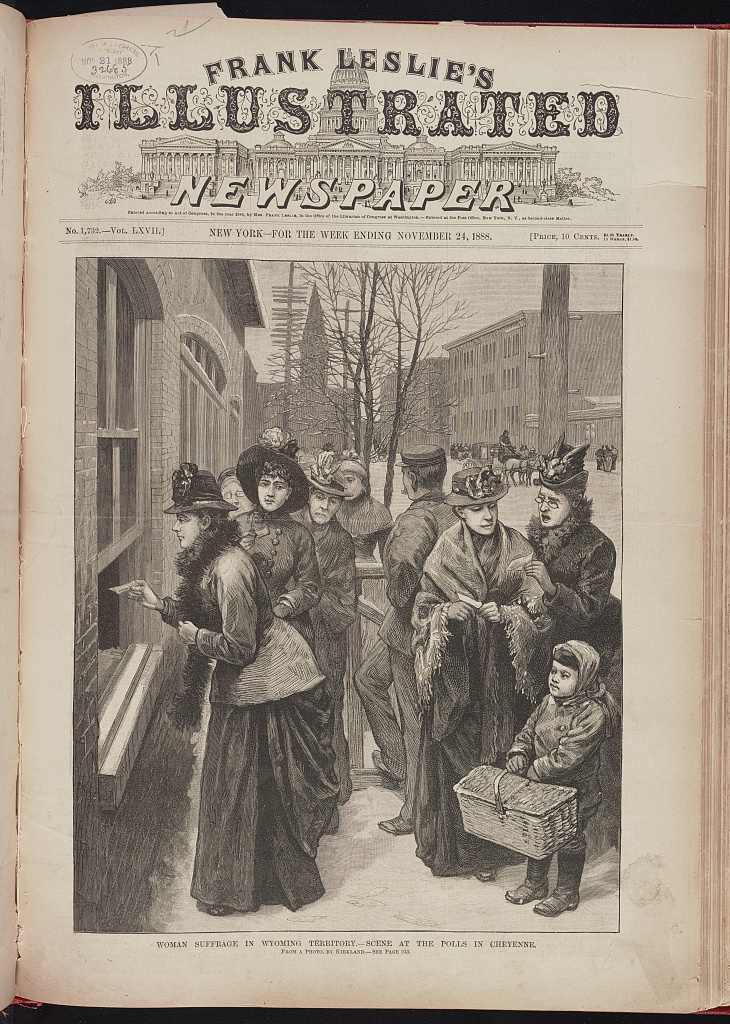

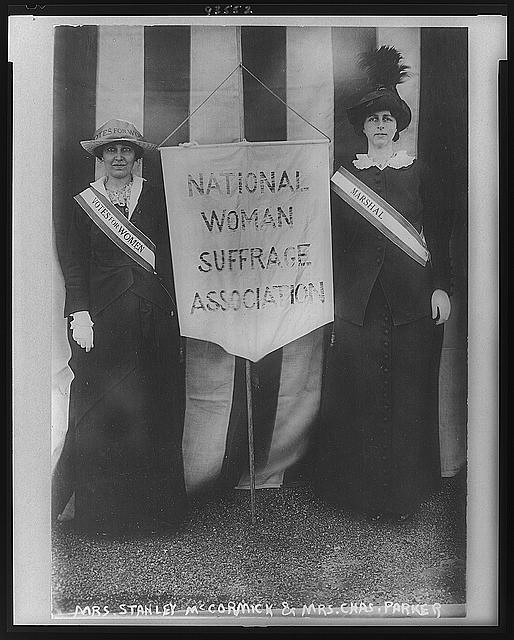

The journey of the 19th Amendment was decades in the making, the culmination of generations of activists and groups advocating for women’s right to vote. Its legislative journey was also long in the making: after repeated attempts to pass the amendment, starting as early as 1878, it finally passed the House of Representatives with a two-thirds majority vote in January of 1918.

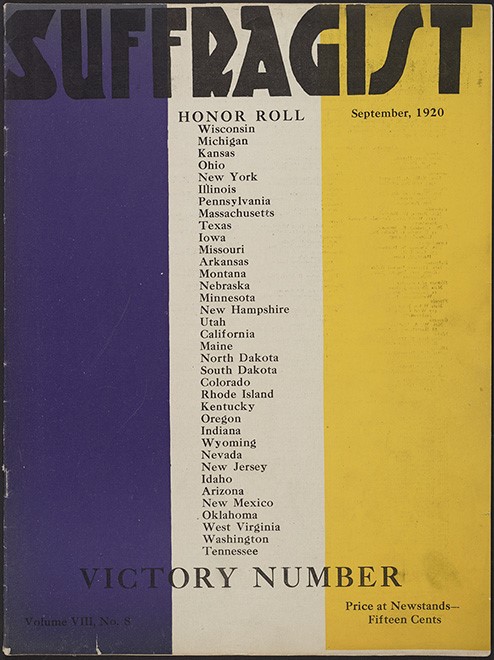

In June 1919, it was approved by the Senate and sent to the states for ratification. Tennessee sealed the amendment’s success when on August 18, 1920, it became the 36th state to sign on, making ratification official and making women’s suffrage law.

But the journey didn’t end with Tennessee’s dramatic clinching vote. The certified record of action of the state’s legislature was sent via train to Washington, D.C., and arrived just over a week later on August 26. (Virginia notably rejected the 19th Amendment in February of 1920 and didn’t formally ratify the it until February 21, 1952.)

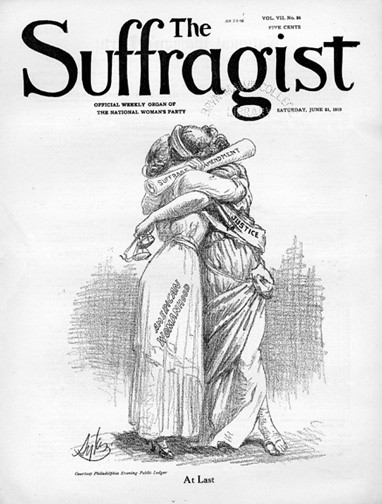

Cover of The Suffragist, the National Woman’s Party’s weekly newsletter, celebrating the passage of the 19th Amendment in the Senate, June 21, 1919. Image courtesy of the Bryn Mawr College Library.

Signing the 19th Amendment

Early the morning of August 26, U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby signed the Amendment without ceremony at his home. In contrast to the formalities and ceremony of other pieces of legislation, no leaders of the suffrage movement were present at the signing, nor were any members of the press, or any recording devices.

This lack of ceremony upset some suffragists, such as Abby Scott Baker of the National Woman’s Party, who declared,

“It was quite tragic. This was the final culmination of the women’s fight, and, women, irrespective of factions, should have been allowed to be present when the proclamation was signed. However, the women of America have fought a big fight and nothing can take from them their triumph.” (From the New York Times, August 27, 1920.)

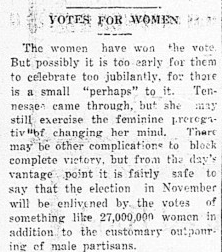

Headline from the New York Times the day after the 19th Amendment was adopted, August 27, 1920. Image courtesy of the New York Times.

Later that day, suffragist and head of the conservative National American Suffrage Associate Carrie Chapman Catt, along with fellow organization member Helen H. Gardiner, were received at the White House by then-president Woodrow Wilson and First Lady Edith Wilson, marking the only governmental celebration of the signing day.

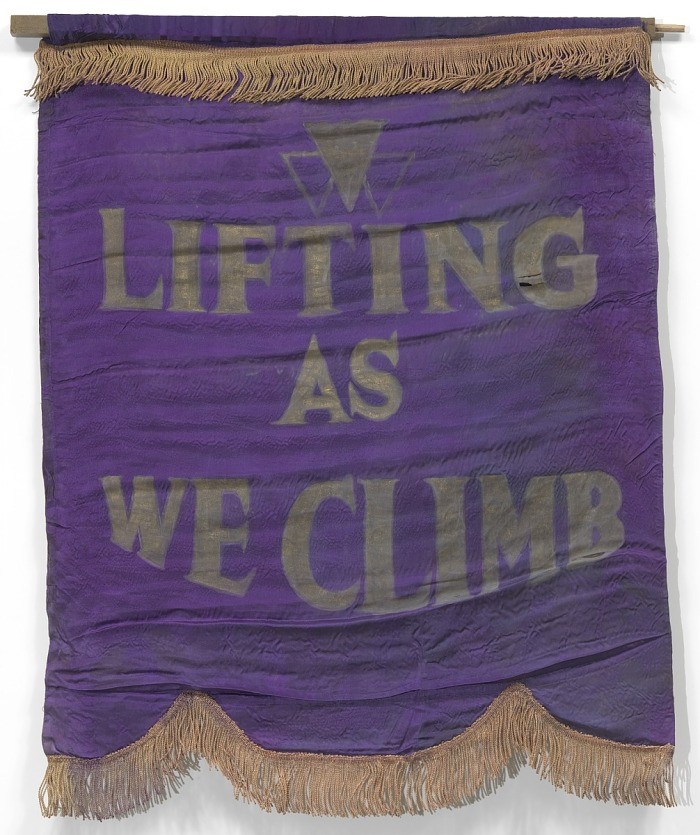

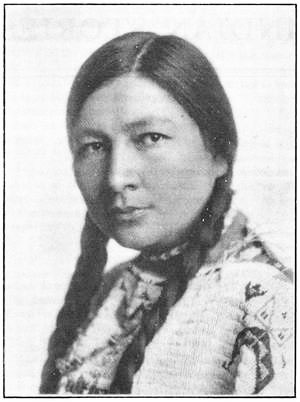

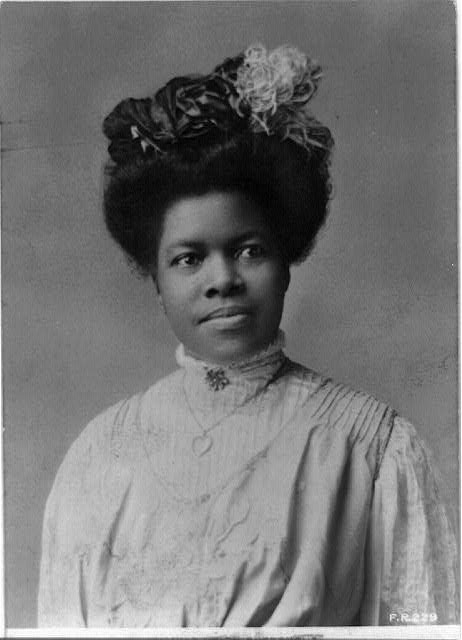

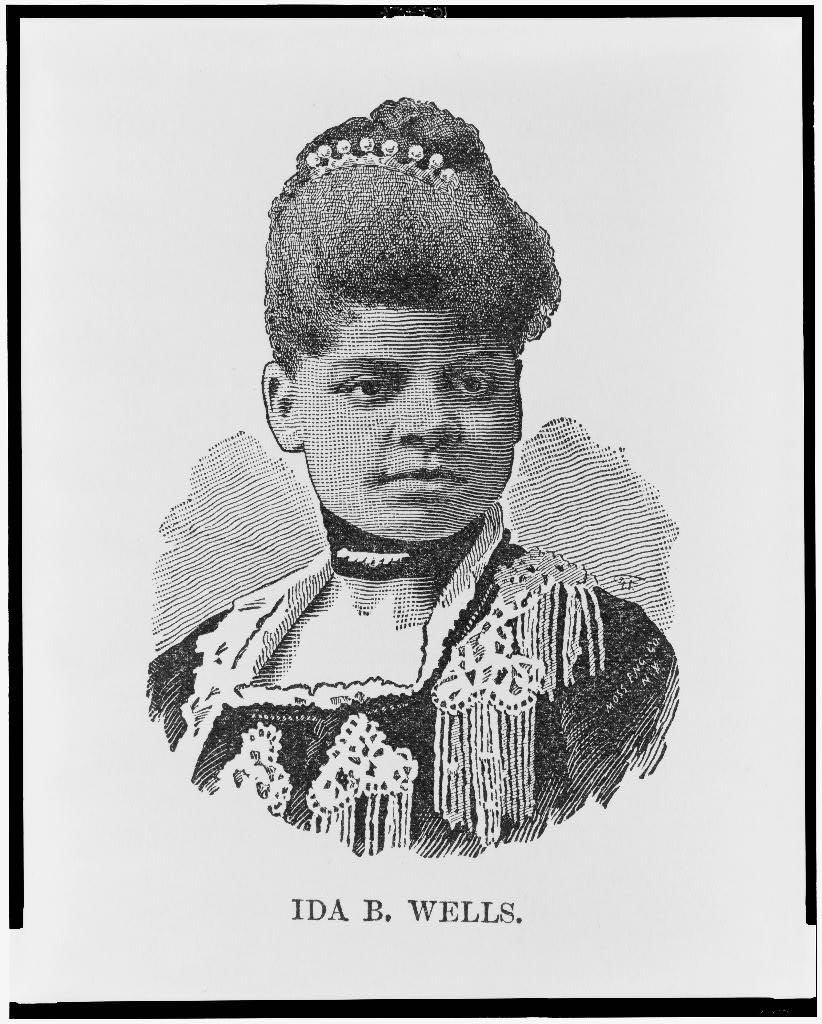

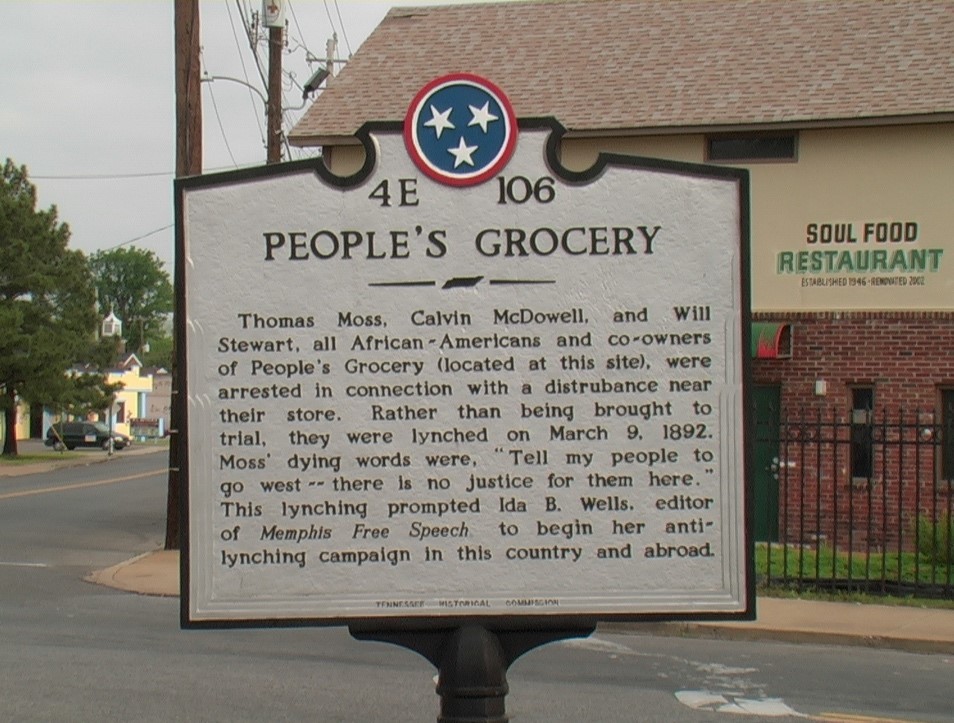

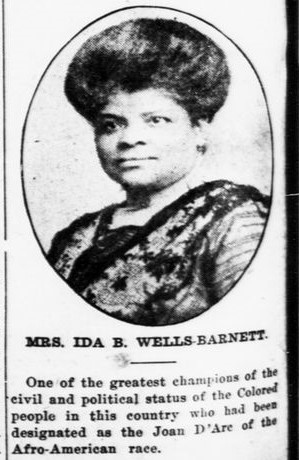

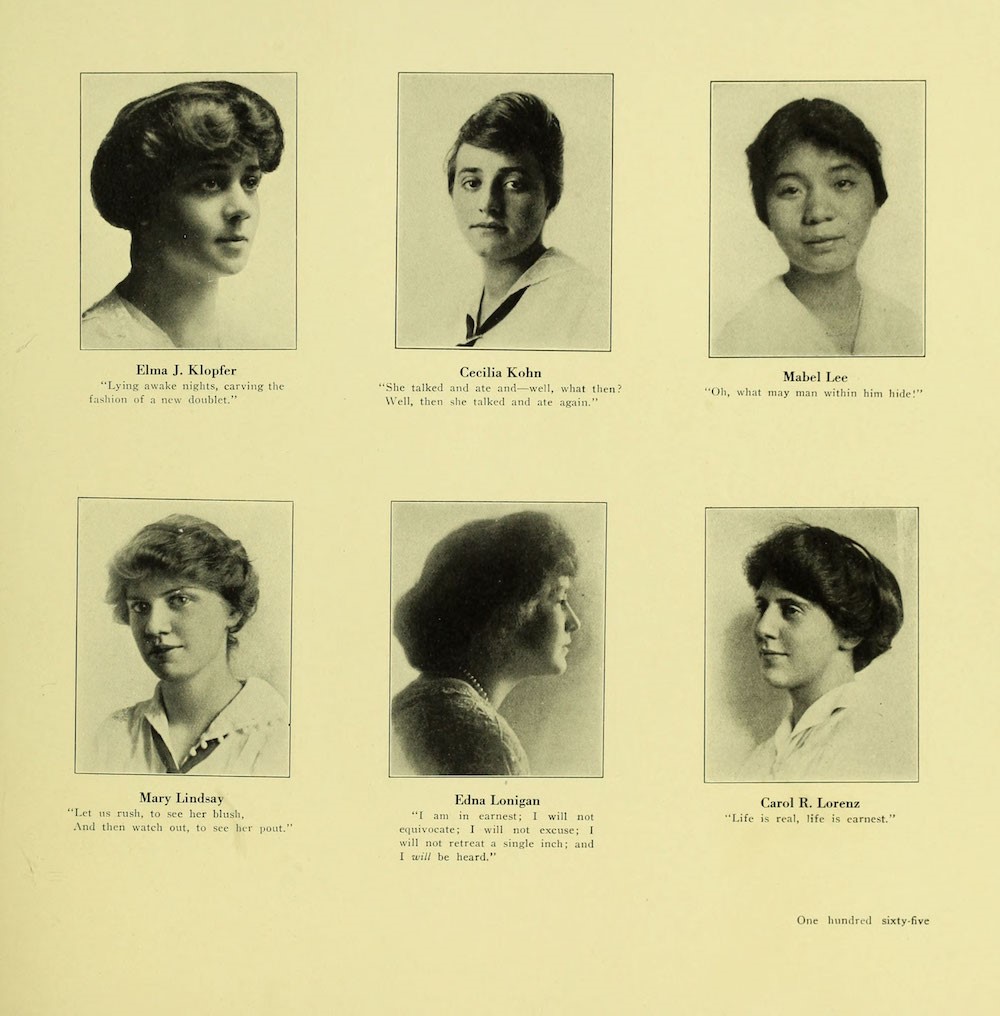

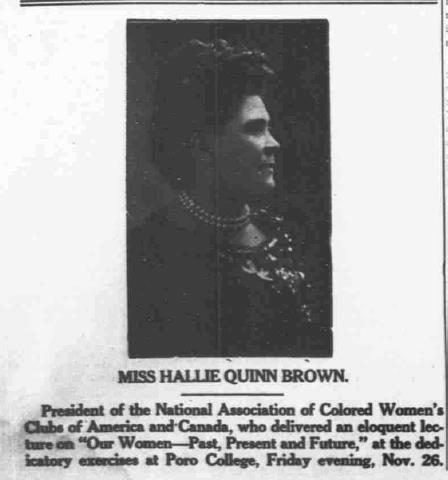

Numerous groups were excluded from the rights extended by the 19th amendment, including Native Americans, women in some U.S. territories, women of Asian descent, and others excluded from obtaining citizenship. African Americans were also systemically prevented from voting through Jim Crow laws and voter suppression, and African American woman activists such as Fannie Lou Hamer and Diane Nash helped to eventually secure the Voting Rights Act of 1965 – another national milestone in the fight to truly secure universal suffrage for all.

Women's Equality Day

In 1973, as the Equal Rights Amendment was going under review in Congress, President Nixon signed Proclamation 4236 declaring August 26 Women’s Equality Day.

This was a symbolic end to the decades-long struggle for women’s suffrage, and due recognition of the scores of activists and groups who had toiled to achieve to right to vote, but the journey toward universal suffrage didn’t stop with the 19th amendment

Countless people are still fighting for their right to vote today, and the milestone of the 19th Amendment is a reminder of how far we have come, and how far we still have to go in pursuit of fully equal voting rights.

Read stories about the people and events that led to the passage of women’s suffrage in the United States.

“Women out in force, Men and women at the voting poll, Oliver and Henry Streets, New York City,” circa 1922. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

“Twelve Reasons Why Women Should Vote.” Image courtesy of the Museum of the City of New York.

2020 marked the centennial of the passage of the 19th Amendment.