Sign up today to discover wonderful reads in one (or all!) of the following categories:

- Biography and Memoir

- Fantasy and Science Fiction

- Fiction A to Z

- History and Current Events

- Mystery

- Romance

Sign up today to discover wonderful reads in one (or all!) of the following categories:

Oral histories are used to understand historical events, actors, and movements from the point of view of real people’s personal experiences.

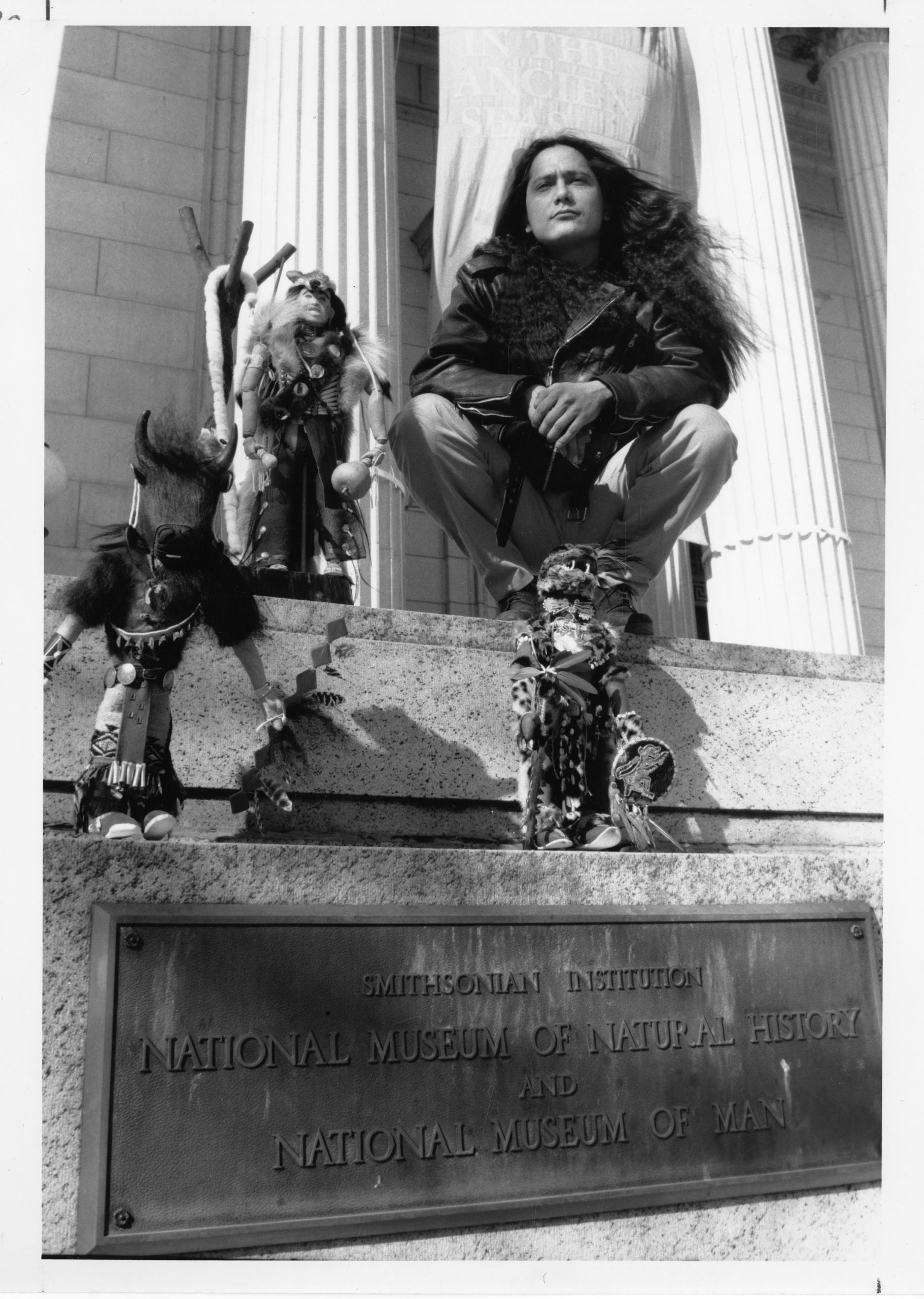

Artist Don Tenoso is a prolific creator, known for his Lakota-style dollmaking that depicts Sioux culture. Tenoso came to the Washington, D.C., area in 1991 as the first artist-in-residence at the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum, where he created new pieces and led demonstrations for the public.

Don Tenoso, circa 1990 at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Tenoso was born in Riverside, California, and is a member of the Hunkpapa, one of the seven bands of the Teton Lakota Nation and part of the Sioux-speaking indigenous population. Tenoso’s mother was born on the Standing Rock reservation in South Dakota, and he is a descendant of One Bull and Sitting Bull. His father was in the U.S. military during Tenoso’s early life and the family often moved around the country and abroad.

The following interview excerpts are from a 2008 oral history with Tenoso. At the time of this interview, he had lived in Arlington for about 14 years. In the full interview, which can be accessed in print at the Center for Local History, Tenoso also discusses his family and lineage, as well as tribal traditions and the Lakota language.

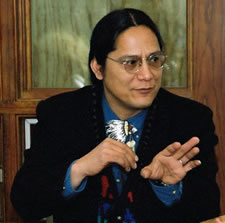

Don Tenoso, circa 2005. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where Tenoso was the university’s first artist-in-residence at the Native American House.

Narrator: Don Tenoso

Interviewer: Tom Dickinson

Date: January 23, 2008

Note: The audio for this interview is currently unavailable.

Don Tenoso: I was the first artist-in-residence in the Natural History Museum. Prior to that they had brought me in for a three-day doll demonstration where they had taken one of the glass cases out of one of the Native halls there in Natural History at Smithsonian and by different artists coming in. Me, a Sioux doll maker, was invited to come up and do that. I guess they had spent like nine months trying to find me. I started dollmaking back in the seventies.

Anyway, in the eighties, ‘86 or so, ‘87, there was an article in American Indian Art magazine that was published about dolls. In ‘86 I believe it was, I had a one-man show down in Andrew Park, Oklahoma and they collected the International Crafts Board for four of my dolls.

So one of them got in that article and then the director over at education in the outreach program saw the doll and they said they wanted to find that guy.

Don Tenoso circa 1991 outside of the National Museum of Natural History with some of his works of art. The doll beside Tenoso is called “Iktorni,” or “trickster doll.” Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

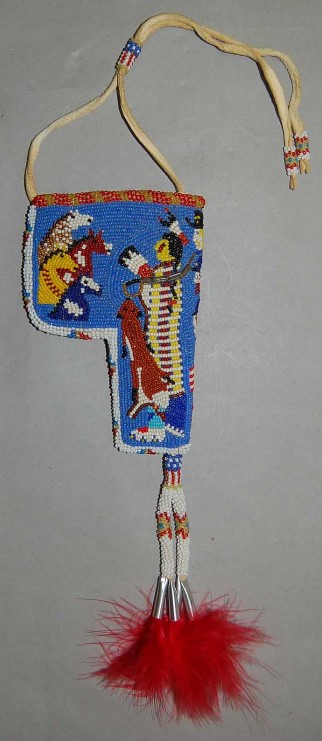

Leather holster created by Tenoso in 2006, covered in a beadwork design. Image courtesy of the British Museum, where the piece is held.

Tom Dickinson: How did you get started doing this [art practice]?

DT: Actually I started when I was in New York. I went out there because I heard that C. W. Post [campus of Long Island University] had a scholarship for Natives who wanted it to be teachers. It turns out they didn’t so I went to the American Indian Community House there in New York.

Actually, backpedal a little bit. I was born in Riverside, California in 1960. In ‘63 we were in France. We were there when de Gaulle kicked us out. So my earliest memories are there when the French high school kids were throwing rocks at us on the playground. They would stone our bus. I remember flying out of there and the U.S. piling up all these brand new, big boxes and stuff and just setting them on fire. Big old wrecking balls smashing holes into runways as you flew out. I also got to see some whales as we flew, that’s how low they went across the ocean. You can see the spouts and little tails going across.

So from there we go to Oklahoma City, so I got to meet all these Natives. They used to call it Indian Territory which is sort of a penal colony for Native Americans starting back through Trail of Tears, Andrew Jackson and all of that stuff.

From there we went and lived in Rapid [City] back where my grandma lived, lot of relatives in Rapid City, South Dakota, in the Black Hills which is our sacred area, which actually by federal courts is still our property. But they offered us $10 million or $100 million or something but we still don’t take it. Because our sacred Wind Cave is there and that’s one of our origin stories. We came from there. The thing about Wind Cave you stand there one hour of the day and it blows your hair back.

So geologists say, “Yeah, there’s probably an underground stream - they haven’t found it yet - flowing and air displacement and that’s causing your hair to go that way.” The only thing is you come back some hours later, same day, and now it’s sucking your hair into the cave. “I guess there’s a tilting rock or something under there that messes with it.” We say that’s Mother Earth breathing, that’s where she breathes from.

Learn more: View a program from the 1992 exhibit Contemporary Plains Indian Dolls, which took place at the Southern Plains Indian Museum and Crafts Center in Anadarko, Oklahoma. The exhibit featured a piece by Don Tenoso (“Gourd Clain Dancer,” figure 10).

This interview was conducted as part of The Many Faces of Arlington oral history project, which sought to document the County’s diverse population as a reflection on the 400th anniversary of the settlement of Jamestown by English colonizers.

The goal of the Arlington Voices project is to showcase the Center for Local History’s oral history collection in a publicly accessible and shareable way.

The Arlington Public Library began collecting oral histories of long-time residents in the 1970s, and since then the scope of the collection has expanded to capture the diverse voices of Arlington’s community. In 2016, staff members and volunteers recorded many additional hours of interviews, building the collection to 575 catalogued oral histories.

To browse our list of narrators indexed by interview subject, check out our community archive. To read a full transcript of an interview, visit the Center for Local History located at Central Library.

A surprisingly open memoir co-authored by the married duo of a world class oncologist and a cancer survivor about love, pain, hope, strength and resilience while navigating the overwhelming breast cancer advocacy movement.

Watch the video: https://youtu.be/5JPqRkpBzp4

About the Authors:

Liza Marshall left her law practice in 2005 to focus on her family and Hope Connections for Cancer Support, of which she is a founding member. In 2006, at the age of forty-three, Liza was diagnosed with triple-negative breast cancer, the most deadly form of the disease. Throughout her treatment and beyond, Liza has been an active volunteer at Hope Connections and other local non-profits, serving on boards, directing development campaigns, and supporting a variety of communities and missions.

John Marshall is a medical oncologist and a professor at Georgetown University, and an internationally recognized expert in gastrointestinal cancers and the development of new treatments for cancer. He has been outspoken on controversial issues in cancer research, including his criticism of the dominance and success of breast cancer advocacy and research at the unfortunate expense of other specialties.

About the Interviewer:

Bethanne Patrick is a Washington Post book reviewer and the editor, most recently, of “The Books That Changed My Life: Reflections by 100 Authors, Actors, Musicians and Other Remarkable People.”

Oral histories are used to understand historical events, actors, and movements from the point of view of real people’s personal experiences.

Walter Tejada’s County Board portrait, circa 2007.

In 2003, J. Walter Tejada became the first person of Latin American heritage to be elected to the Arlington County Board, or to any governing body in Northern Virginia.

Tejada served as County Board Chair in 2008 and 2013.

Tejada was born in El Salvador and immigrated to the United States at age 13, first settling with his family in Brooklyn, New York, and later moving to Trenton, New Jersey. After attending college and playing soccer at Keystone Junior College and Mercer College, he eventually moved to Arlington in 1987.

Tejada got his start as an activist and organizer after witnessing inequities faced by members of the Latinx community. He initially worked in groups addressing fair housing, job opportunities, and the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). He also helped to establish a Salvadoran festival in Arlington, starting in 1995, focusing on Salvadoran culture.

The front page of El Pregonero, the official Spanish-language newspaper of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Washington, D.C., on March 13, 2003, following Tejada’s election to the County Board.

In 2003, Tejada was elected to the Arlington County Board in a special election following the death of Board member Charles P. Monroe. Tejada defeated longtime GOP activist Mike W. Clancy in the contest.

During his time on the board, Tejada continued to advocate for immigrant and Spanish-speaking communities, and served on numerous task forces and groups, including as chair on the governor’s Latino Advisory Commission.

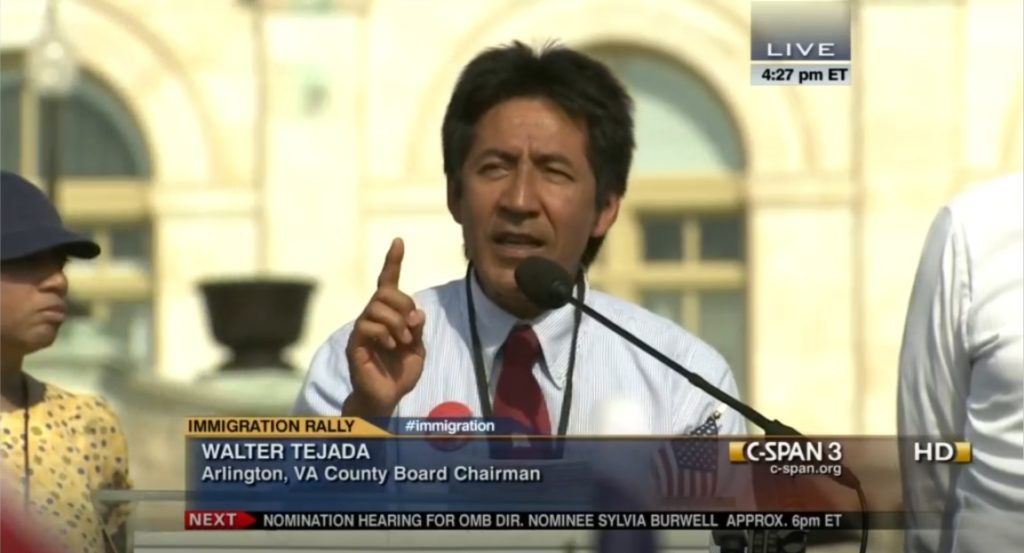

J. Walter Tejada speaking at the National Rally for Citizenship on the West Lawn of the Capitol on April 10, 2013. Image courtesy of C-SPAN.

From left to right: County Board members J. Walter Tejada, John Vihstadt, Jay Fisette, Mary Hynes and Libby Garvey in 2014.

Since his time in County government, he was appointed to the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority Board of Directors and is president of the Virginia Latino Leaders Council.

In the following oral history interview, conducted prior to his election to the County Board, Tejada discusses his childhood, coming to Arlington, and his early work in activism. In these excerpts from the interview, he discusses first impressions of the County and his work with LULAC’S Council 4609, which encompasses Arlington.

This interview is available in full at the Center for Local History. Note: The audio for this interview is currently not available.

Narrator: J. Walter Tejada

Interviewer: Ingrid Kauffman

Date: October 27, 2000

J. Walter Tejada: One of the things I saw when I lived in DC - actually, one of the first things I recognized was that - actually since I started visiting Robin [Liten-Tejada] when she went to school here -- is that DC had a much larger Latino population than New Jersey, and I liked that. Remember, I mentioned that when we lived in New York there weren't that many Salvadorans at all, even when we lived in New Jersey, there was one person that was Salvadoran, and he lived like 10 miles away. It was odd that I came here and suddenly there was a Salvadoran population.

Ingrid Kauffman: What year was that?

WT: 1987. I thought, “this is great.” There were some restaurants; I hadn't eaten pupusas for years, which is one of my favorite Salvadoran dishes, just like almost every day. I saw this and it really piqued my interest. In fact, it was a determining point why I ended up moving here, when we were talking about what we were going to do with our lives. I'd come to visit and see all this and I liked that. The climate here, so many people from different backgrounds, different perspectives and accents, cultural activities - to me, it was like a paradise for these activities. When I was working in D.C. I also saw that the Latino community was really - first of all, there was no political power. Then - the community - not all but certainly a good portion of the community finds itself in a very tough socio-economic situation.

WT: Three things [LULAC Council 4609] did were voter registration, citizenship, and leadership development. That part I liked because it made it so broad for different things. I decided I was going to be involved in that aspect, because we would promote meetings, forums, community forums, where elected officials or public officials would meet with the community to address issues of concern with the community, sort of like putting a little bridge into what needed - the issues of importance. I started, and I would go to places and grab chairs, move them around, set up the coffee machine, make sure donuts were there.

We did forums on gang prevention activities, the educational system in Arlington, how it was being responsive to Latinos or not. We've done forums in the business community - what opportunities there could be to incorporate Latinos into the business world. We did citizenship workshops where we published that on a certain day people could come in with all their material that we would specify, like passport, proof of where they lived, proof where they worked, birth certificates for their kids, and helped them fill out these applications in order to apply to become citizens. We would have lawyer friends who would come and volunteer in these workshops so that we can help people.

The goal of the Arlington Voices project is to showcase the Center for Local History’s oral history collection in a publicly accessible and shareable way.

The Arlington Public Library began collecting oral histories of long-time residents in the 1970s, and since then the scope of the collection has expanded to capture the diverse voices of Arlington’s community. In 2016, staff members and volunteers recorded many additional hours of interviews, building the collection to 575 catalogued oral histories.

To browse our list of narrators indexed by interview subject, check out our community archive. To read a full transcript of an interview, visit the Center for Local History located at Central Library.

September 15 - October 15 is National Hispanic Heritage Month, a time when we honor the cultures and contributions of both Hispanic and Latino Americans as we celebrate heritage rooted in all Latin American countries.

Join us to celebrate the contributions of Hispanic Americans to American history, through books and programs for all ages.

{{ e.description | plainText | trunc(descMax) }} [see more] RSVP

The Center for Local History has recently digitized many additional photographs from the Community Archives taken at the Pentagon at the time of September 11, 2001, by Mike Defina, a fire captain with the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority Fire and Rescue Department.

National Airport personnel deployed to the Pentagon Sept. 12, 2001. L to R: CCT Mike Fetsko, Deputy Fire Marshal David Norris, Captain John Durrer, Paramedic Captain David Testa, Captain Mike Defino, Tech. Ralph Cornell, Paramedic Mike Murphy, Tech. Troy Hutchinson, Tech. Paul Purcell, Firefighter. Photo: Mike Defina.

These images are just a few of the Community Archives collection Records Related to the September 11, 2001 Terrorist Attacks on the Pentagon, which is made up of textual materials, photographs, some memorabilia, and audio-visual materials. The bulk of the collection dates from 2001-2002 and features photographs of the aftermath and days after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the Pentagon. (Note: some of these photos may contain sensitive or disturbing material).

That morning a westbound plane took off from Dulles airport, was hijacked by terrorists and crashed into the Pentagon. One hundred and eighty-nine people died in the crash, including the 64 passengers on Flight 77. On the same morning two more hijacked planes were flown into the World Trade Center in New York City, and a fourth hijacked plane crashed in rural Pennsylvania. Nearly 3,000 people died in the tragedy, changing both the country and Arlington forever.

Firefighters and first responders from Arlington County, Fort Myer, and Reagan National Airport were essential in coordinating the Pentagon rescue and response, arriving within minutes of the plane crash.

Arlington County Fire Department took the lead, establishing an Incident Command System across the region to respond to the emergency. Firefighters were able to get the fire under control on the first day, but it took three days to fully extinguish.

The images in this collection depict both the horrific nature of the crash and Pentagon fires, the resilience and bravery of the first responders, and many spontaneous memorial events.

A memorial of flags, flowers, and signs near the Pentagon following the September 11 terrorist attack. Photo: Mike Defina.

Additional physical materials in the collection are held in the Arlington Community Archives for research use, including many thank-you cards written by school children to the firefighters of the Arlington Fire Department, County Manager Ron Carlee's papers used during the response, after-action reports, ephemera from memorial services, and VHS tape recordings of memorial events.

While these additional items have yet to be digitized, those who wish to research them may use the online finding aid to determine which boxes or folders would be useful and/or contact the Center for Local History to make a research consultation appointment.

Oral histories from the five-year anniversary of September 11, 2001 are also available online in the Center for Local History's digitized Community Archive.

Arlington County Fire Department members pose with children in front of a mural created to thank them for their service. Photo: Mike Defina.

Do you have Arlington materials related to the events September 11, 2001 that you would like to donate?

The Center for Local History (CLH) collects, preserves, and shares historical documents that tell the history of Arlington County, its citizens, organizations, businesses, and social issues. Learn about how you can help to build Arlington's community history on the CLH Donation webpage.

The Friends of the Arlington Public Library will contribute $1 to the Arlington Food Assistance Center (AFAC) on behalf of each of the 4,525 people who completed this year's Summer Reading challenge:

Summer Reading: Adventure Begins at Your Library is made possible through the generosity of the Friends of the Arlington Public Library and the Washington Nationals and is hosted in partnership with Outdoor Lab and Arlington County Department of Cultural Affairs.

JobNow can help you:

To get started, login using your library card number, then create a free Brainfuse account!

Oral histories are used to understand historical events, actors, and movements from the point of view of real people’s personal experiences.

Arlington has a lengthy history of legacy floral shops, and among those was Buckingham Florist, a mainstay of the Buckingham neighborhood for almost 80 years.

Buckingham Florist was founded by Myer and Jean Bassin in Arlington in 1942, and the couple later opened a second location in Coral Hills, Maryland. The business did floral arrangements for a variety of events and venues, with the nearby Arlington National Cemetery among their primary sites of business.

At one point, Buckingham Florist was the primary supplier of flowers for the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. The shop’s federal connections didn’t stop there, however: one of the shop’s floral designers, Elmer “Rusty” Young, went on to serve as a florist in the White House in the Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon administrations. Young was appointed the first White House Chief Floral Designer by Jacqueline Kennedy, and continued in that position throughout the rest of his career.

Buckingham Florist, right, in 1996.

The shop moved to its long-term location at 301 North Glebe Road in the bustling Buckingham Shopping Center in the mid-1950s, having previously been located on the south side of Glebe. Myer and Jean Bassin’s son Neil Bassin ran Buckingham Florist throughout the latter half of the 20th century. He sold the shop in the mid-2000s, and the Buckingham storefront closed permanently in 2017.

In this oral history interview, Neil Bassin (1932-2019) discusses the legacy of the business and how the shop supplied its flowers. The interview in full goes on to discuss other topics, such as changes in the floral industry and the business environment of Buckingham throughout the 20th century.

Narrator: Neil Bassin

Interviewer: Virginia Smith

Date: May 14, 2012

Photos of the Bassin family from the February 8, 1965, issue of the Northern Virginia Sun. Image courtesy of Virginia Chronicle.

Neil Bassin: In most aspects of the florist business, we were very successful because of the location we were in. People knew us. And that’s, I would say, the major factor in why our business was so successful, until the people met me or my mother, or you know. And just personal business, where the people knew us. I mean, we had people when they were born. We had them when they were married, and we had them when they died because the business is over sixty years.

Virginia Smith: That’s a nice legacy, isn’t it? Sixty years of business.

NB: Yeah, it’s a long time.

VS: Tell me who your suppliers were of flowers.

NB: Well, lots. Mostly, downtown florists, wholesalers. And when I first got in, it was downtown wholesalers. They were all—

VS: Is that the name of it? Downtown—?

NB: No.

VS: Oh, multiple—?

NB: They were mostly around one block downtown.

VS: Where was that block?

NB: It was between Fourteenth and Thirteenth on the street before K Street. K Street was a park in those days.

VS: Yes.

NB: Like a little park. And then down Fourteenth Street, on the right was Schaffer’s Retail Florist.

VS: Okay, but Shaffer was a wholesaler also—

NB: Then, Shaffer was a wholesaler. McCallum Sauber was a wholesaler, and they were really instrumental in helping us get in business because my uncle sort of knew the owners. And they did help us. My uncle was very artistic, and he was a big help in getting us into the business. But, there were Paul’s Wholesale Florist and Goody Brothers.

VS: Oh, I know that name.

NB: And around the corner was District Wholesale, and Flowers Incorporated, which was also a wholesale florist. And so they were all in one area until they sold that block and razed that block, where they all moved out and spread out.

Advertisement for Buckingham Florist in the Washington, D.C., Yellow Pages in 1960. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Elmer “Rusty” Young, Chief Floral Designer at the White House, prepares an arrangement in the Floral Room, August 28, 1963. Young was previously a floral designer at Buckingham Florist. Image courtesy of the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library of Museum.

The goal of the Arlington Voices project is to showcase the Center for Local History’s oral history collection in a publicly accessible and shareable way.

The Arlington Public Library began collecting oral histories of long-time residents in the 1970s, and since then the scope of the collection has expanded to capture the diverse voices of Arlington’s community. In 2016, staff members and volunteers recorded many additional hours of interviews, building the collection to 575 catalogued oral histories.

To browse our list of narrators indexed by interview subject, check out our community archive. To read a full transcript of an interview, visit the Center for Local History located at Central Library.

We champion the power of stories, information and ideas.

We create space for culture and connection.

We embrace inclusion and diverse points of view.