A Lifetime at the Center of Arlington's Airport History

Oral histories are used to understand historical events, actors, and movements from the point of view of real people’s personal experiences.

Rayfield Barber (1914-2011) was one of the few witnesses to the full trajectory of Arlington’s airport history over the course of his life, and was key to the success of the County's regional airfields.

Among one of the first airport employees in the burgeoning field of commercial flying, he had a distinguished career at both Washington-Hoover Airport and the National Airport.

Barber was born in 1914 in North Carolina, and came to live in Alexandria around 1920. Barber attended the Parker-Gray School, which at the time was Alexandria’s only primary school for Black children.

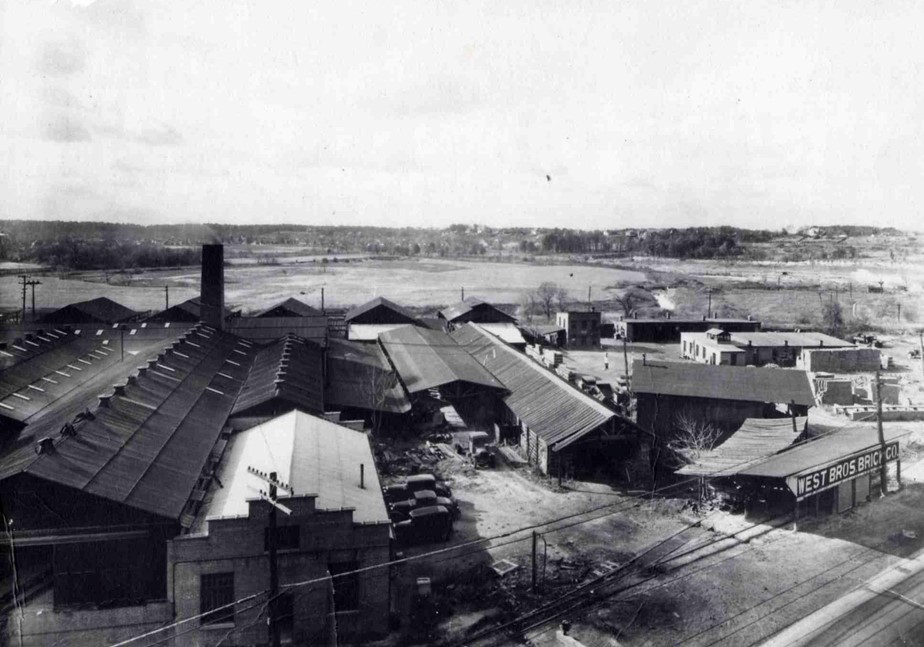

In 1932, Barber began working for the West Brothers Brick company, an Arlington-based operation that used materials from the clay deposits on the Potomac to create its product. Barber worked as a machine operator at the factory until 1937.

Panoramic of the West Brothers brickyard, circa 1903.

Read and listen to Rayfield Barber speaking about his time working at the West Brothers Brick Company in our blog post for April 2021.

When Barber was still working at the brick factory, the Hoover Airport was in its nescient stages. The airfield opened in 1926, and merged with the adjacent Washington Airport in 1933. It was known as one of the most dangerous airfields in the country at this point, in part due to Military Road – a large thoroughfare that brought car traffic between the two airfields.

Barber began working at the airfield in the summer of 1939. In this excerpt from his oral history interview, he describes the early scenes of the airport.

Narrator: Rayfield Barber

Interviewers: Edmund Campbell and Cas Cocklin

Date: July 17, 1991

Edmund Campbell: Tell us something about the Hoover Airport, what it looked like and what were the conditions?

Rayfield Barber: It had a hangar that was right on No. 1 Highway. You know, just right off Number 1 Highway. The terminal was setting, say, a little to the northwest of the hangar.

Cas Cocklin: Sort of where that marina is now?

RB: Yes, that's where it was. Right back of the hangar was where the airplanes coming in would come down on the runway.

EC: Only one runway, wasn't it?

RB: That's all.

EC: And where did that runway go from?

RB: It ran right on down close to the experimental farm. You see the roadway would come up by the restaurant and food.

EC: The roadway ran right through the runway, right across the runway, didn't it?

RB: That road would run right across the runway and they had those lights set up.

CC: Stoplights.

RB: Stoplights.

CC: To stop the traffic if a plane was landing or taking off.

RB: That's right. See, because that road was coming right along from, coming away from Arlington Cemetery . . .

CC: Going toward Route One.

Listen to this audio from Barber's interview:

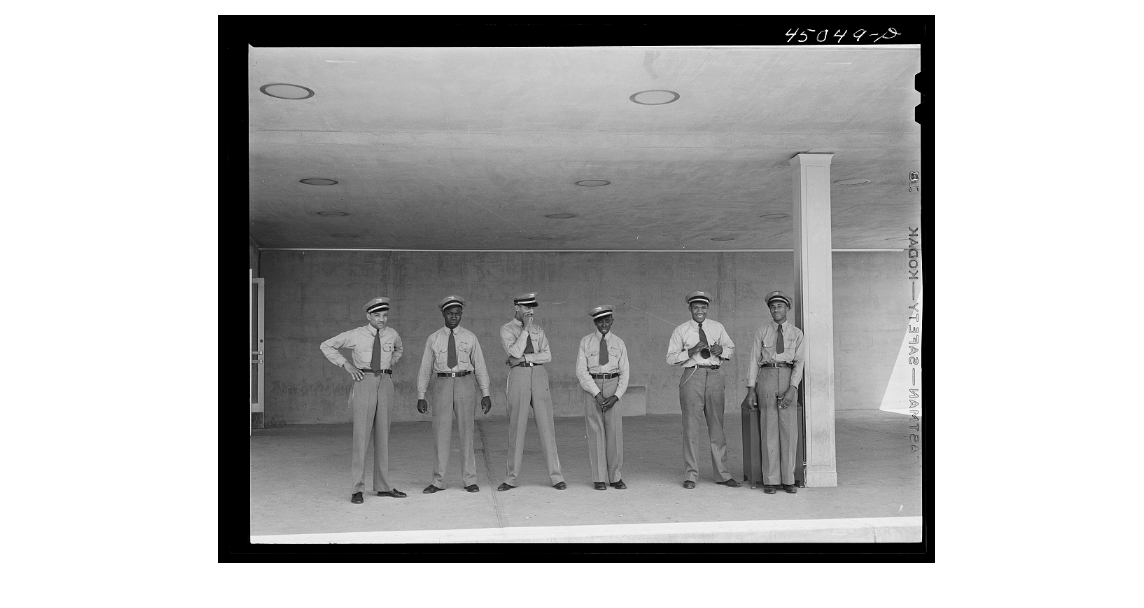

Porters at the airfield were initially called “Redcaps” due to the red hats they were required to wear as part of their uniforms. Later they were known more generally as “skycaps," most notably at the National Airport. Initially, Barber was initially paid only in tips, ranging from 10 cents to a dollar, depending on the customer.

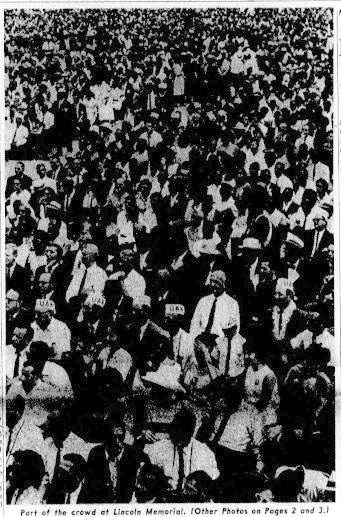

“ ’Skycaps’ at the entrance to the administration building. Municipal airport, Washington, D.C,” circa 1941. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Simultaneously, Barber also worked as a taxi driver. He was one of the first Black operators of a taxicab service in Northern Virginia, which he ran through the early 1940s before the start of WWII. When the United States entered the war, it became too difficult to obtain equipment such as tires due to the war production effort.

During this time, Black people in Arlington had to travel to Washington, D.C., to receive medical care, as Virginia hospitals were segregated and had limited resources for Black patients, and expectant mothers were often barred from the maternity ward in full. The Friendly Cab Company was another local service that addressed this issue, providing ride services to Black customers beginning in 1947.

At the Washington-Hoover Airport, Barber met notable figures such as Horace Dodge, Clark Gable, Wallace Berry, the Roosevelts, and the Kennedy family. At the time, Washington Hoover was the only major airport in the area, so it was a thoroughfare for notable individuals.

Flying was also still a new form of transportation and was no exception to the Jim Crow laws that affected every level of life for Black Americans. This made commercial flying largely exclusive to wealthy, white customers.

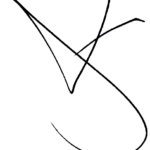

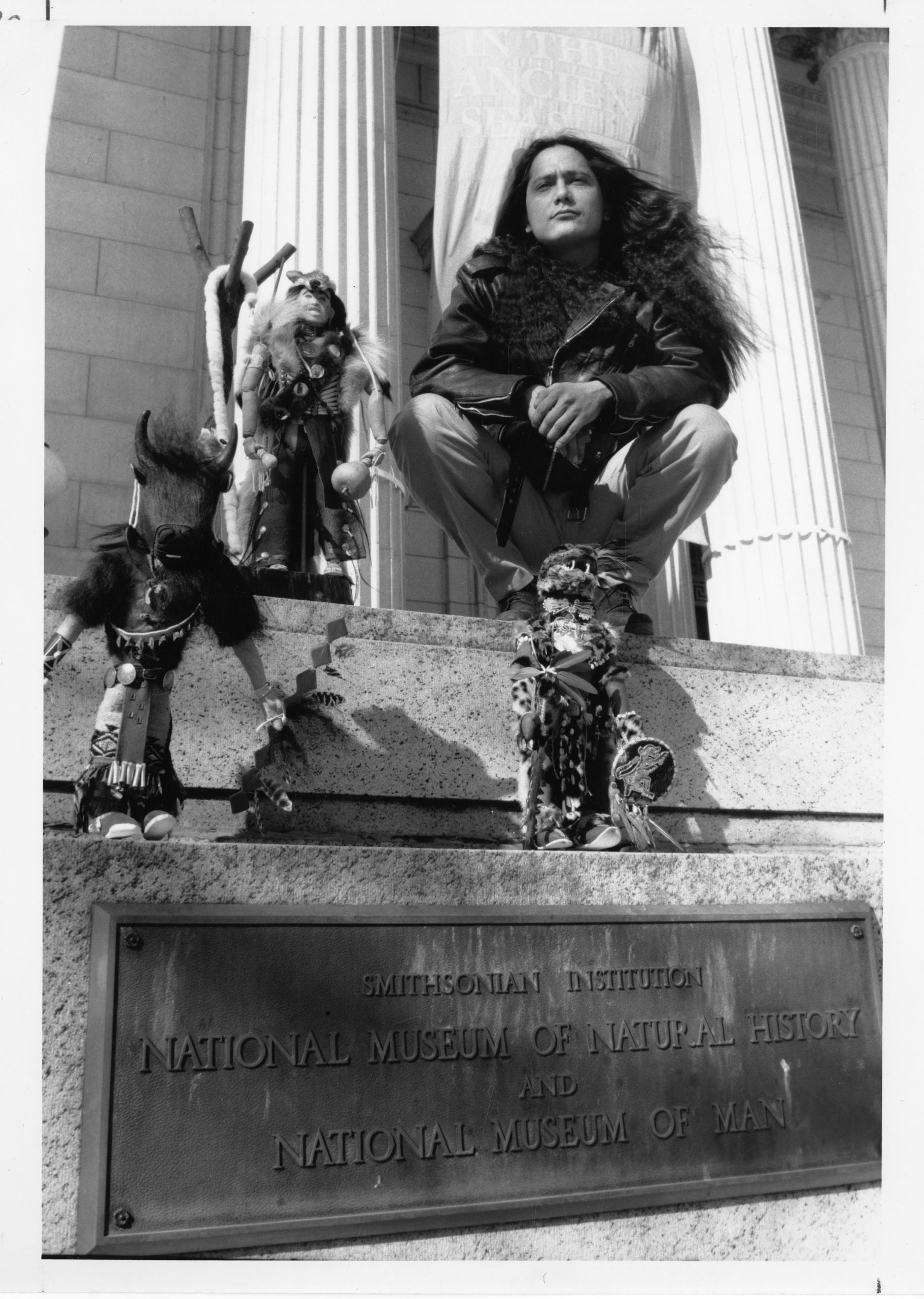

Reproduction image of a National Archives print that reads: "A full view of the four-motored Douglas C-54 skymaster dubbed the 'Flying White House', an ATC transport specially built for President Roosevelt." From RG 13.

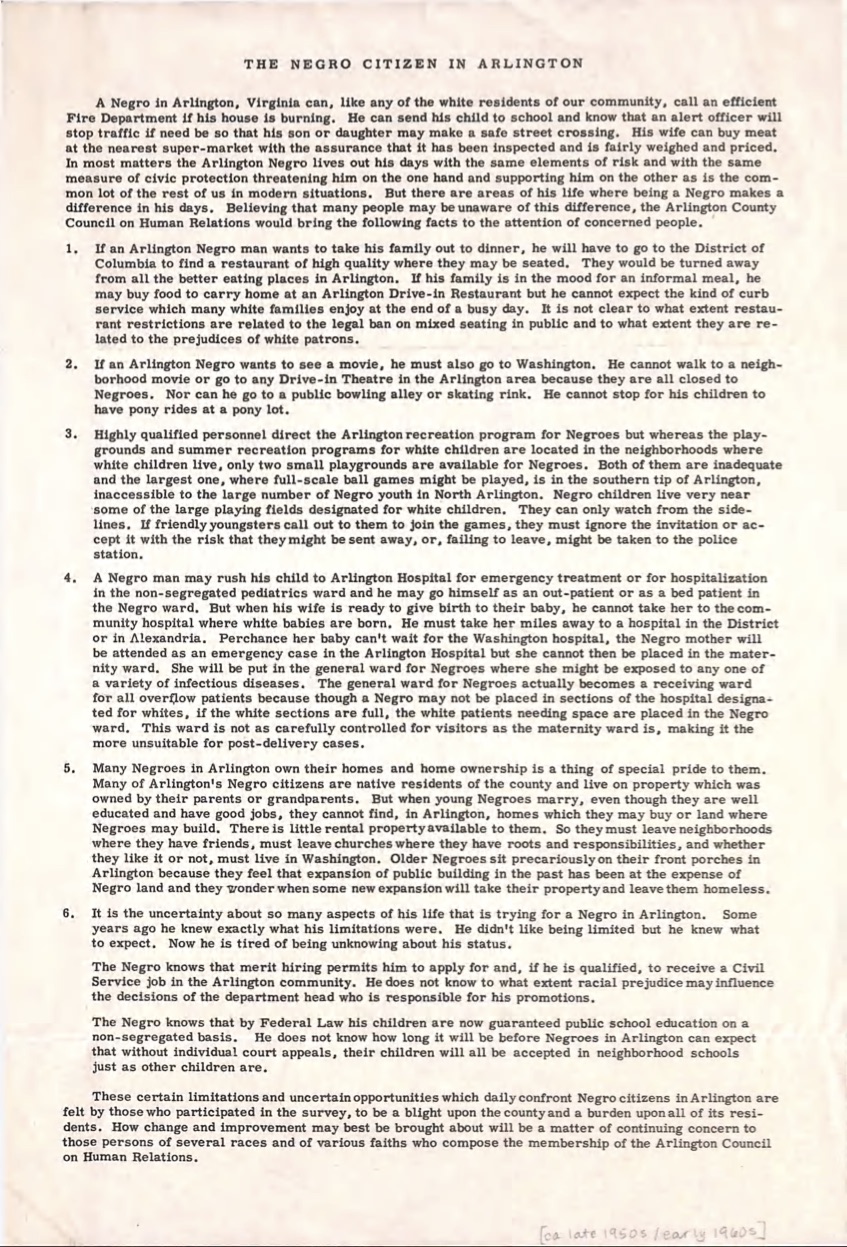

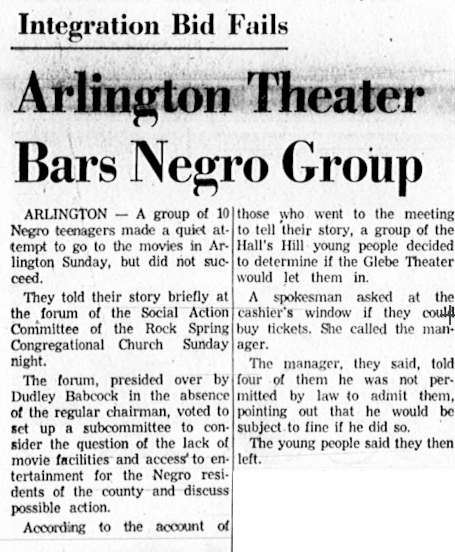

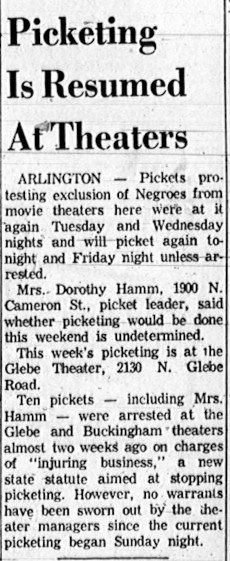

In the 1930s and 1940s, airports across the South began to segregate their facilities, either by sanctioned law or racist informal practices. In 1944, during World War II, members of the Tuskegee Airmen integrated the National Airport’s cafeteria after initially being denied service. However, after the war ended, segregation soon re-installed itself in airport facilities. After pressure from President Truman, the airport desegregated its restaurants in 1948, but only the next year, a D.C. resident brought a suit against the Air Terminal Services arguing that she had been denied service on account of her race.

In June 1941, when Hoover closed, Barber moved to the National Airport. On its opening day, Barber was the first on the runway, unloading one of three planes that inaugurated the debut (and American Airlines DC-3). As one of three skycaps working at the time, he earned $1.25 for 10 hours of work each day.

Barber worked at National Airport until the early 1990s, accruing more than 50 years of airport experience. Barber’s interview describes many fascinating aspects of his life, such as fortuitously being home from work the day of the 14th Street Bridge crash, to meeting every first lady since Eleanor Roosevelt over the course of his career. In this selection, Barber sums up his work at the airport:

EC: As soon as Hoover Airport was closed, you moved over to National, did you?

RB: That's right.

EC: And acted as a porter there?

RB: That's right.

EC: And you still are a porter at National?

RB: I'm still there. I'm considering retiring.

EC: But you haven't retired yet?

RB: I haven't retired yet.

EC: So, you have been a porter either at Hoover Airport or at National Airport or both for how long?

RB: About fifty‑two years. Fifty‑two years. I had been at National fifty years. I went to National June 16th, 1941.

EC: They had a special ceremony, didn't they, last month for you?

RB: Yeah, they had a special ceremony at Crystal City Marriott Hotel and a real special one was over at Crystal City building they sometime call No. 3, that's when Mr. Robb was there, and former governor Holton of Virginia.

Listen to this audio from Barber's interview:

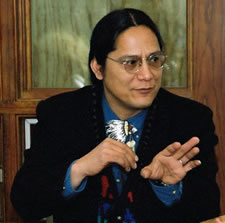

Additional photos of Rayfield Barber at Washington National Airport, circa 1990s. Photos by former County photographer Deborah Ernst.

The goal of the Arlington Voices project is to showcase the Center for Local History’s oral history collection in a publicly accessible and shareable way.

The Arlington Public Library began collecting oral histories of long-time residents in the 1970s, and since then the scope of the collection has expanded to capture the diverse voices of Arlington’s community. In 2016, staff members and volunteers recorded many additional hours of interviews, building the collection to 575 catalogued oral histories.

To browse our list of narrators indexed by interview subject, check out our community archive. To read a full transcript of an interview, make an appointment to visit the Center for Local History located at Central Library.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Charlie Clark Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields

![Flying White House Reproduction image of a National Archives print that reads: A full view of the four-motored Douglas C-54 skymaster dubbed the 'Flying White House', an ATC transport specially built for President Roosevelt. It has flown over 44 countries and established six world records since it was put into service exactly a year ago [1944]. Seven pilots are seen walking in front of the plane. 1945, 1 print, b&w, 8 x 10 in..](https://library.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/13-5081_original_-1-scaled.jpg)