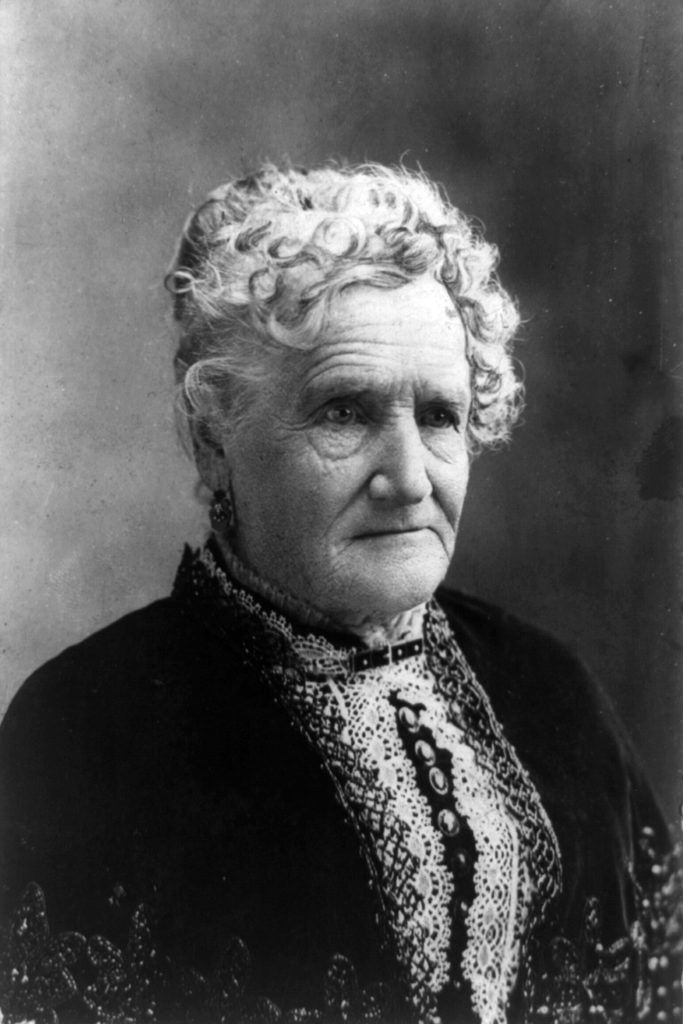

Dorothy Hamm (1919-2004)

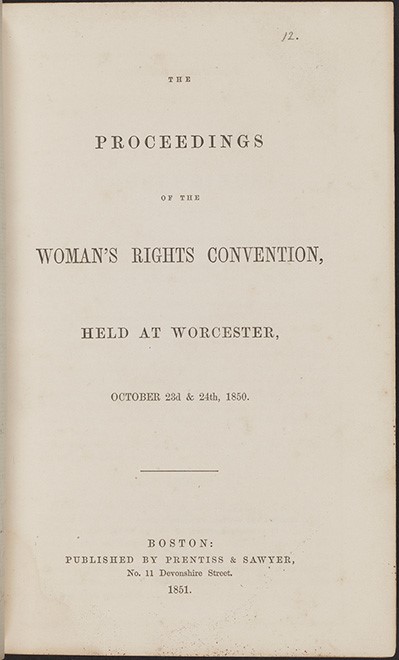

Celebrate Black History Month and the 100th anniversary of the 19th Amendment with stories about women who have used their voices and their votes to better their communities and help shape the United States.

For decades, Dorothy Hamm was at the forefront of the civil rights movement in Arlington, working tirelessly to bring equality to the County. She led the charge to successfully desegregate Arlington’s schools and theaters, and was involved in numerous community organizations and leadership positions.

Early Life

Dorothy Hamm was born in 1919 in Caroline County, Virginia, in a family of seven children. The only school that accepted African-American students was six miles away from their home, so in 1926 the family moved to Fairfax County where the children could attend elementary school.

However, Virginia was still a segregated state, and when Hamm graduated from primary school the family found that there was no junior high or high school for African-American students within a thirty-five-mile radius. Instead, because her mother was a government employee, Dorothy was able to attend secondary schools in Washington, D.C. She went on to enroll in Miner Teacher’s College, also in D.C.. She also attended classes at the Cortez Peters School of Business and George Washington University.

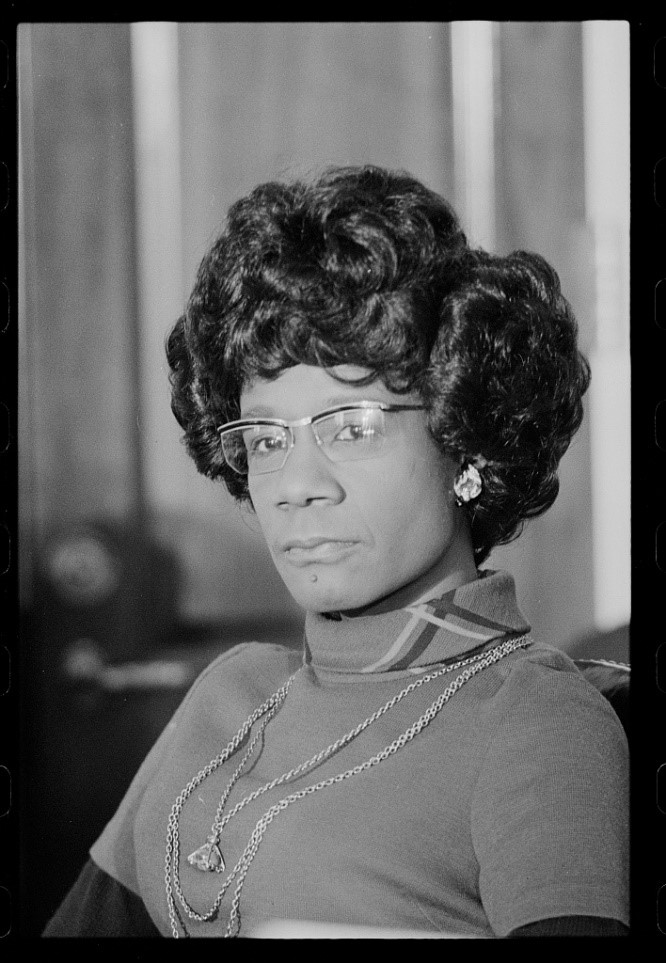

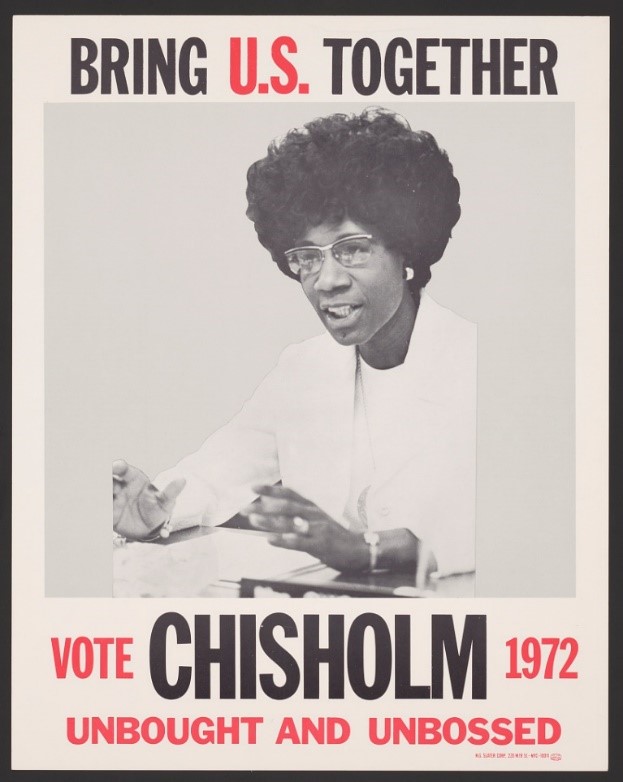

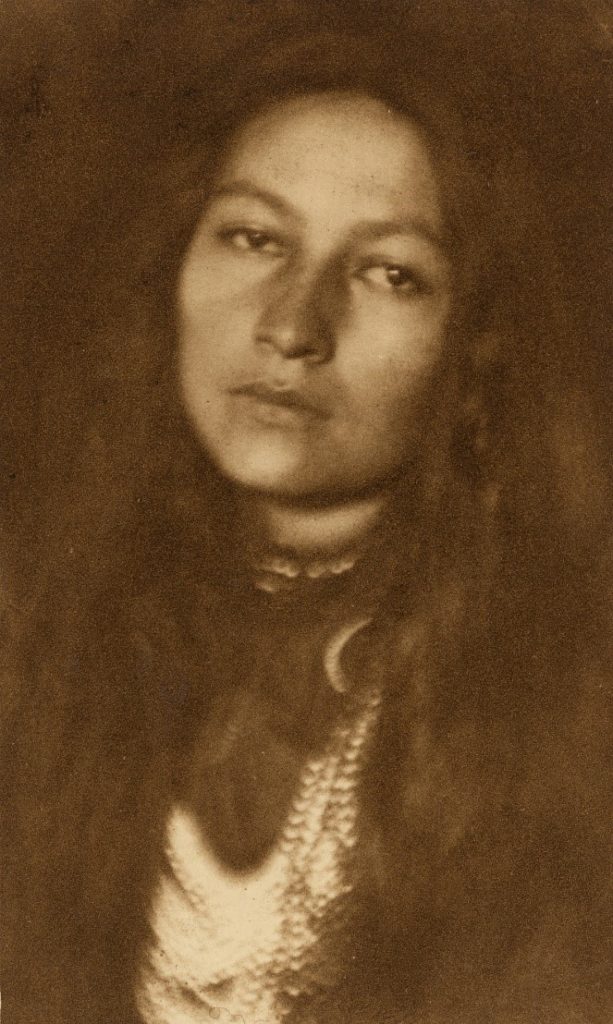

Image courtesy of Carmela Hamm, from the Library of Virginia.

Hamm married Edward Leslie Hamm, Sr., in 1942 and the couple moved to Arlington in 1950, where they would raise their three children. During this time, Hamm worked in numerous government positions, including as an administrator in the Army Surgeon General’s Office, where she worked until 1963.

The catalyst for Hamm’s involvement in the civil rights movement came in the form of the 1954 Supreme Court decision that ruled segregation illegal in public schools.

Arlington Public Schools

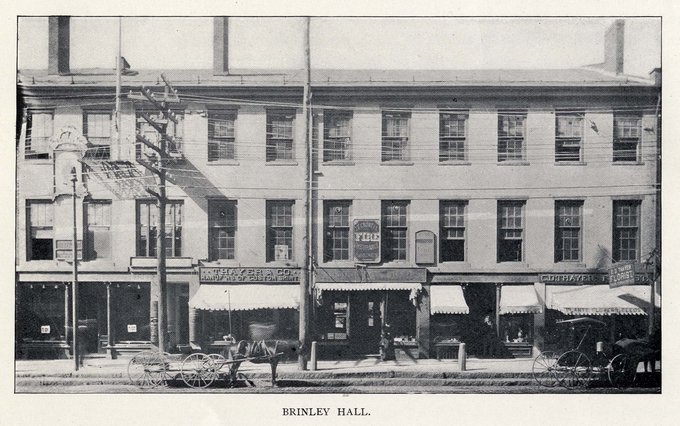

In 1956, Hamm, along with her husband, became plaintiffs in the first civil action case filed to integrate the Arlington Public School system. When no action towards integration had been taken a year after the suit was filed, Hamm and her husband took their oldest son, Edward Leslie Jr., to enroll at Stratford Junior High School. They, and other African-American students who attempted to enroll in the still segregated Arlington schools, were denied admission that year. In September 1957, a few days after the opening of the school year, crosses were burned on the lawns of two Arlington families, and at the Calloway United Methodist Church, a central location for organizers in the effort to desegregate the schools, and a site of workshops held by ministers, lawyers and educators preparing parents and students for school integration.

Over the course of this process, Hamm recalled in interviews many experiences with discrimination and intimidation.

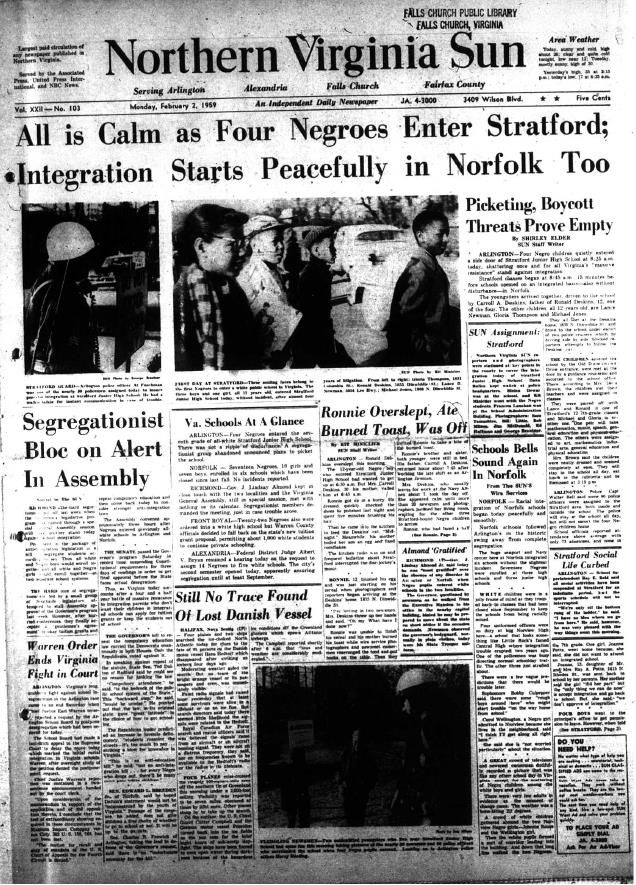

On January 19, 1959, Senator Harry F. Byrd’s statewide policy of “massive resistance” to the Supreme Court ruling was outlawed by the Virginia Supreme Court.

On February 2, Ronald Deskins, Michael Jones, Lance Newman, and Gloria Thompson were enrolled as the first black students at Stratford Junior High, making Arlington the first county in Virginia to integrate its schools. Hamm’s sons would enter Stratford later that year.

In 1960 Dorothy Hamm was a plaintiff in another case, a court action to eliminate the pupil placement form, which was used to exclusively assign African-American students to certain schools as a means to get around the Supreme Court’s ruling on desegregation.

In 1961, Hamm was again a plaintiff in a court action to integrate the athletic program of the Arlington Public Schools, after Hamm’s son had been barred from participating in Stratford’s wrestling program because of the physical contact between Black and white students. As a result of the court action, discrimination in Arlington athletic programs was declared to be illegal.

Civic Life

In 1963, Hamm was the plaintiff in a civil action case to eliminate the poll tax and remove the race designation from public forms and voting records in Arlington County. (Read "If you Don't Vote, You Don't Count", our story from August 15, 2019, about the history of the poll tax in Arlington County, to learn more.)

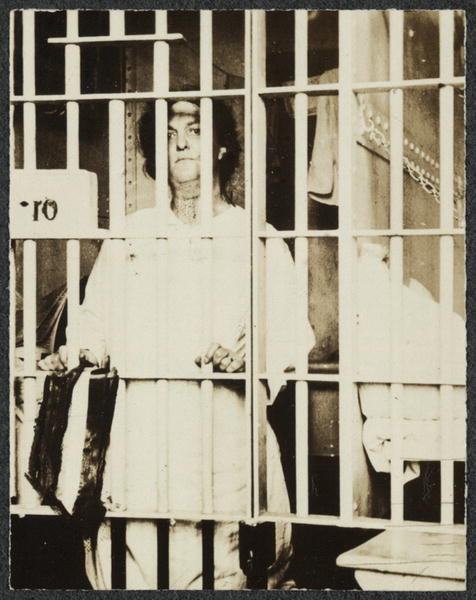

The same year, Hamm also became involved in the fight to desegregate Arlington’s theaters. She initiated another civil court suit and helped to organize what would become a year of picketing efforts in protest of segregation. Along with four other protesters, Hamm was arrested for picketing at the Glebe Theater. The theater owner then struck a deal with the protesters that if they ceased picketing for thirty days, he would admit African-American patrons to the theater. This was successful, and Hamm and her son Edward Leslie Jr., became the first African-American customers to be admitted.

Hamm and her husband also participated in the 1963 March on Washington, helping to organize bus transportation to take Arlington residents into the city to take part in the March. In 1968, they also participated in the Poor People’s March on Washington, and helped to provide food and housing for fellow marchers.

Hamm continued her political activism as a delegate to Arlington County and Virginia State conventions in 1964 and was appointed Assistant Registrar and Chief Election Officer in Arlington’s Woodlawn precinct. She also worked with the Congress on Racial Equality (CORE) as they organized in Arlington and served as an officer of elections in Arlington for more than twenty-seven years.

Writing

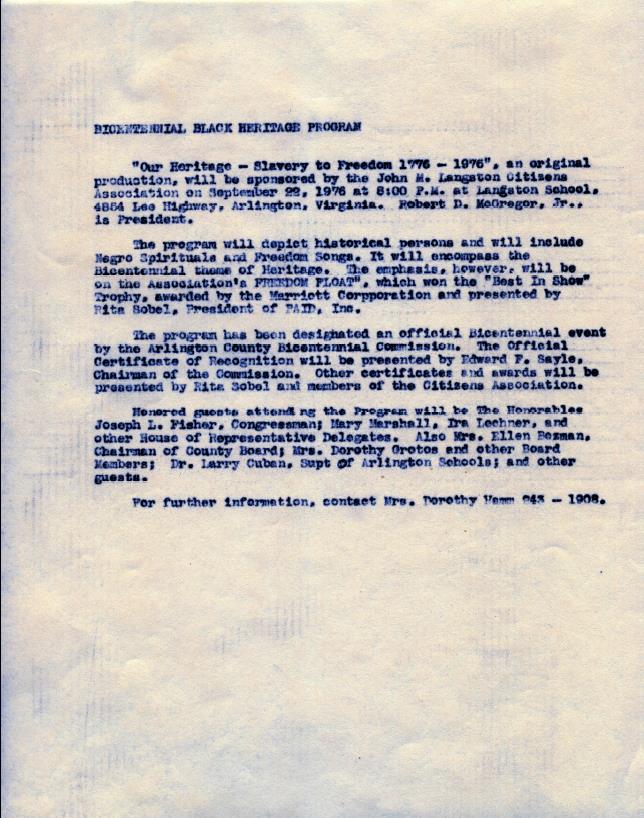

Dorothy Hamm was also known for her work as a poet and playwright.

In 1976, her play “Our Heritage: Slavery to Freedom 1776-1976” was designated as an official bicentennial event in Arlington County. In 1984, she wrote and directed the play “Our Struggle for Equality,” which was performed by the drama club of Calloway United Methodist Church and later developed into a documentary for television.

Legacy

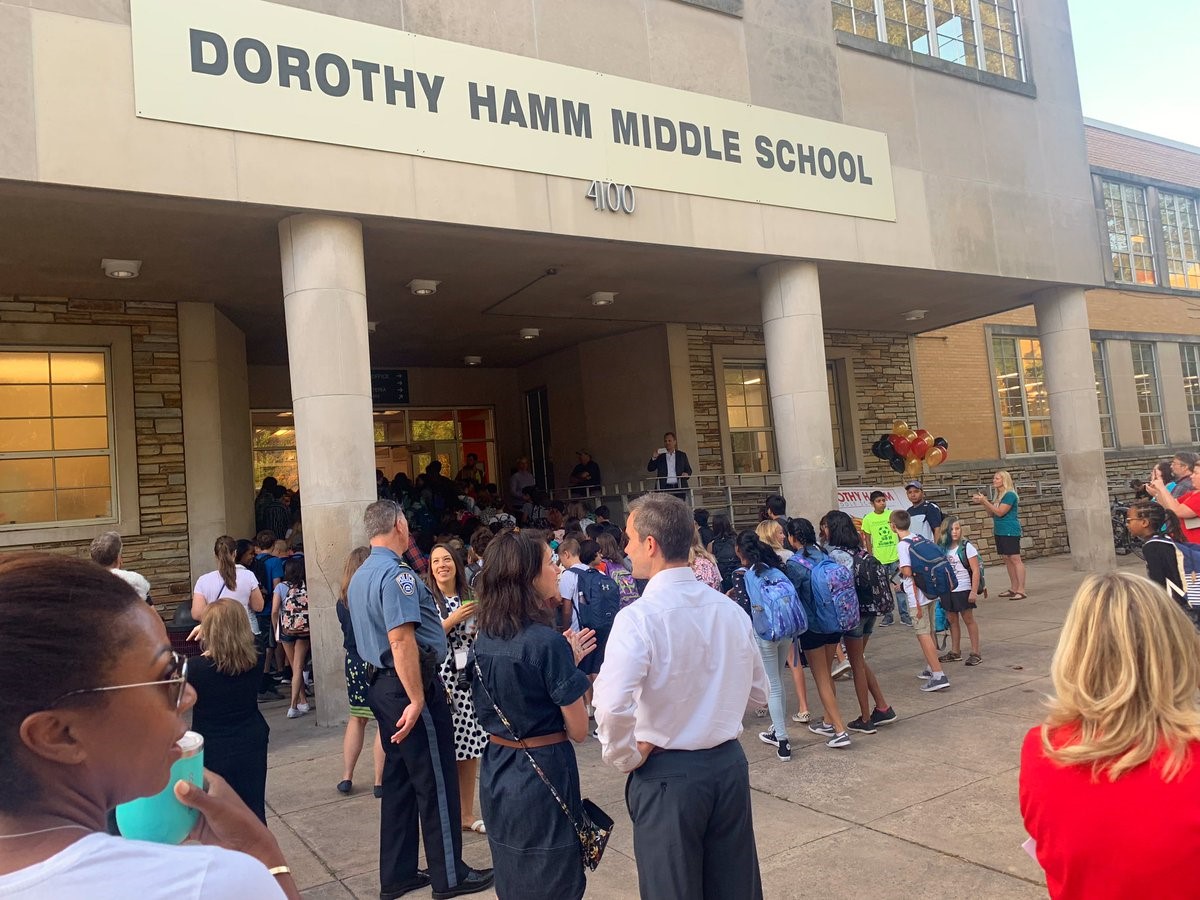

Dorothy Hamm died in 2004, but her legacy and mark on Arlington live on. On March 1, 2002, the Virginia Legislature’s House Joint Resolution No. 458 was enacted commending Hamm and her efforts in the civil rights movement. And in 2019, the Dorothy Hamm Middle School began its first year named in her honor (in the building that formerly was the site of Stratford Junior High and the H-B Woodlawn Secondary Program).

In her autobiography, Hamm wrote about her response to the question of why she fought so hard for equal education and other equal opportunities. She writes:

“Even now, I am asked the same questions. There are many reasons, but one of the most important was my determination to answer the “Why can’t I?” question raised by our eight-year-old son, Bernard Caldwell Hamm. … Finally, I had to truthfully answer his ‘Why can’t I?’ question and explain to him that Stratford was for White children and he could not attend because he was a colored boy. I knew then that with the help of others, I had to fight to help change the ‘Separate but Equal Laws.’”

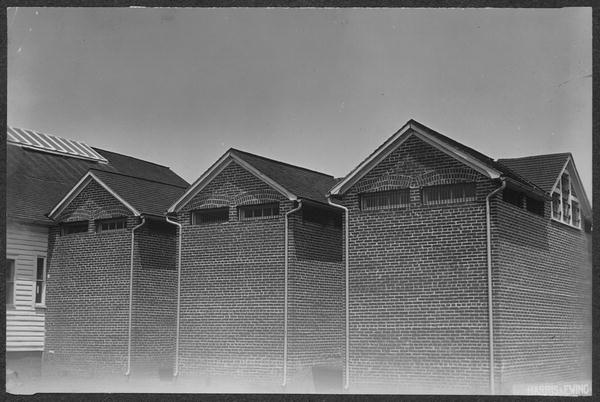

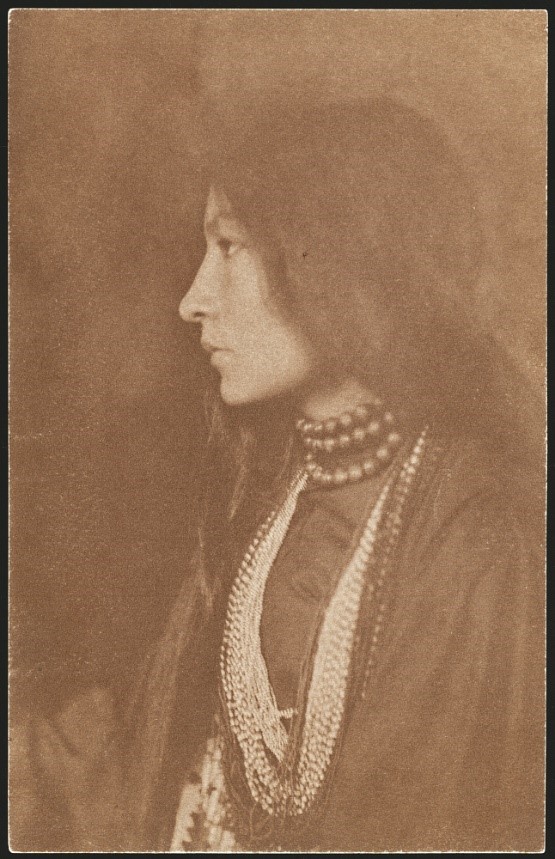

Dorothy Hamm Middle School, which was named in Hamm’s honor in 2019. Image courtesy of Arlington Public Schools.

Learn More

“Notable Women of Arlington: Third Series,” published by the Arlington County Commission on the Status of Women.

“Integration of Arlington County Schools: My Story,” by Dorothy Hamm.

Interview Dorothy M. Hamm, conducted in 1986, VA 975.5295 A7243oh ser.3 no.58.

The Dorothy M. Hamm Papers, 1937-1977, VA/ARCH RG 349.

![Alice Paul banner Photograph of Alice Paul emerging from National Woman's Party headquarters holding banner, followed by Dora Lewis (with no banner). Unidentified women stand with a banner in doorway of building. Banner Paul carries reads: "The Time Has Come to Conquer or Submit, For Us There Is But One Choice. [I] Have Made It. President Wilson." Paul is leading picket line from headquarters to the White House.](https://library.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Alice-Paul-banner.jpg)