Lutrelle Fleming Parker, Sr. was a tireless advocate for progress in Arlington County who left a legacy of remarkable civic engagement that spanned the Civil Rights Movement and desegregation of the County’s schools and businesses.

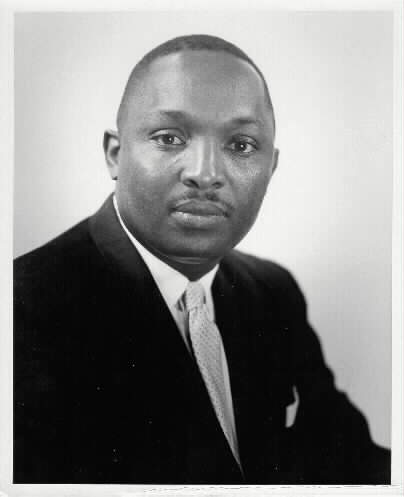

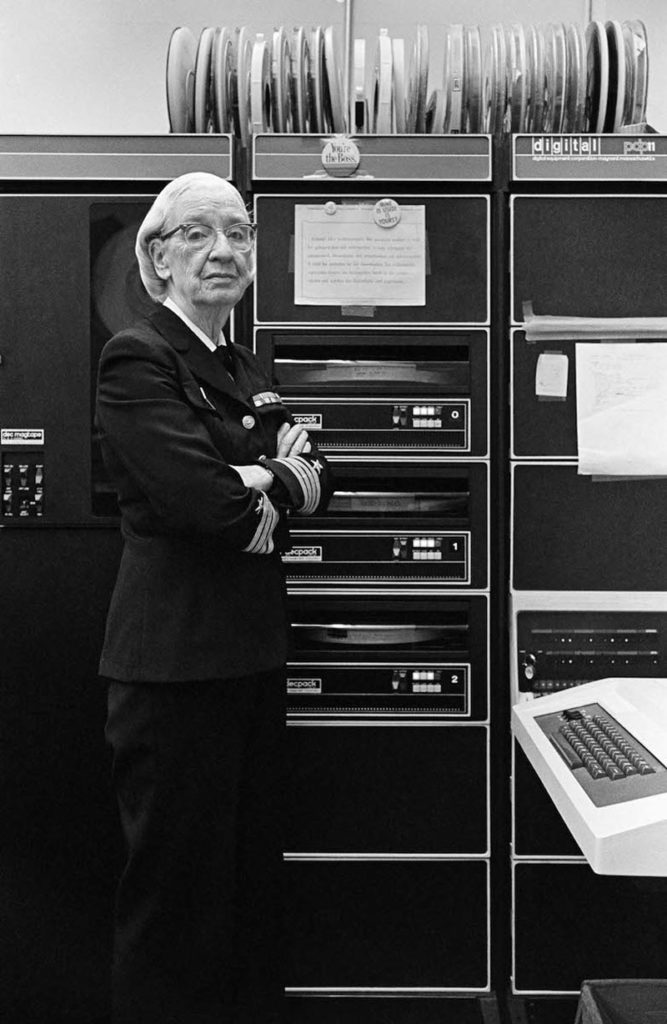

Photo of Lutrelle – Source: Susanna McBee, “Arlington County See Fervent Donor Plea,” The Washington Post, January 5, 1961.

Born in Newport News, Virginia in 1924, Parker served in the U.S. Navy on the HSS Manderson Victory during World War II as one of the Navy’s first black officers. His commitment to the Navy lasted 40 years, retiring from the Navy Reserves in 1982.

After the war, Parker worked at the U.S. Patent Office in 1947 while also studying engineering at Howard University. He began as a patent examiner and later performed a wide range of jobs for this office during his long career, including being a trial attorney, examiner-in-chief, and deputy commissioner of the office. He received his Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering from Howard in 1949, the same year that he moved from Washington, D.C., to the predominantly African-American Arlington neighborhood of Green Valley with his wife, Lillian Madeleine Parker.

He continued to pursue his education and was among the first four African American students accepted to Georgetown University Law School, graduating in 1952. They purchased a house at 3024 18th Street South in the Nauck Neighborhood (present-day Green Valley) by June of 1950.

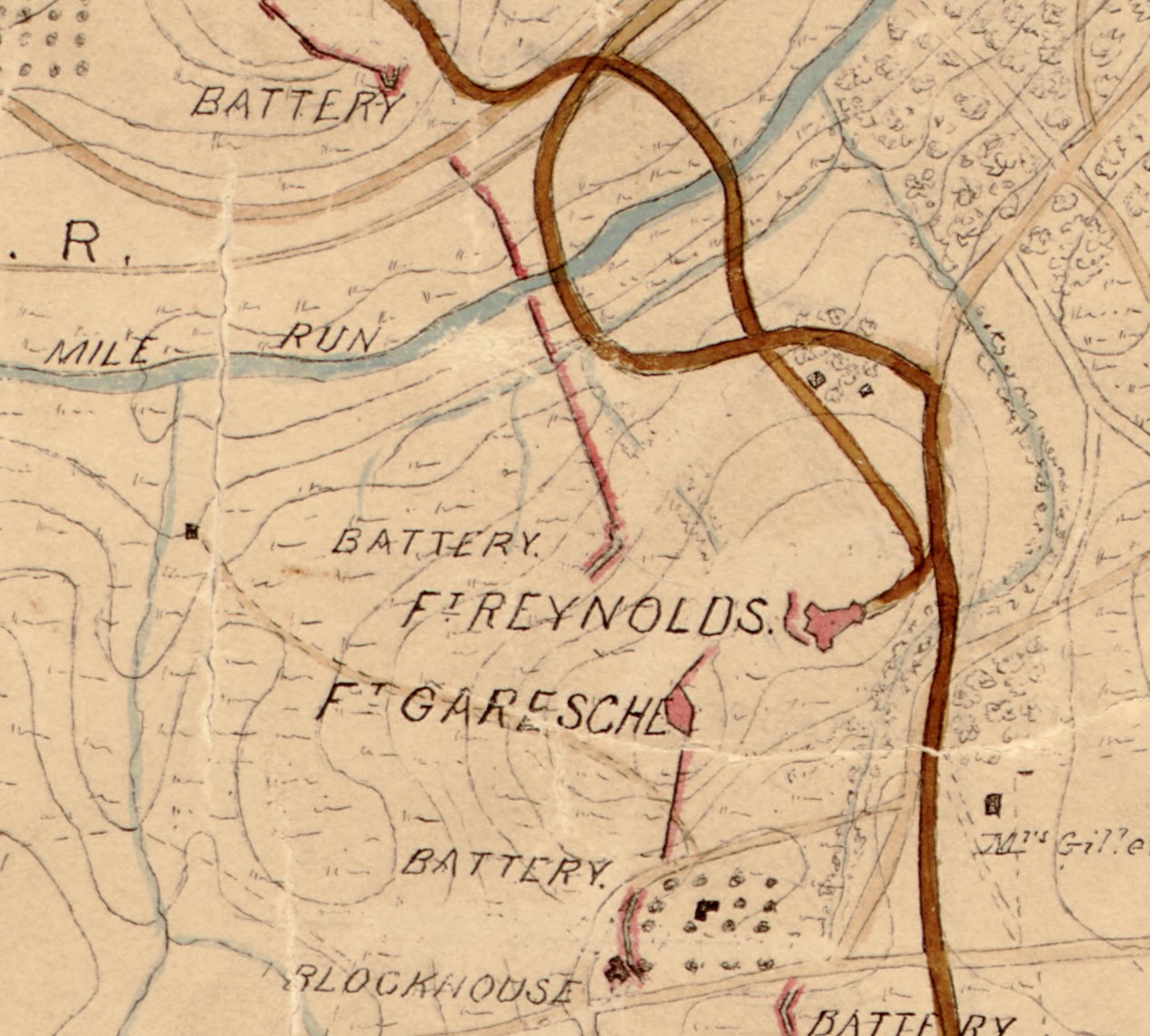

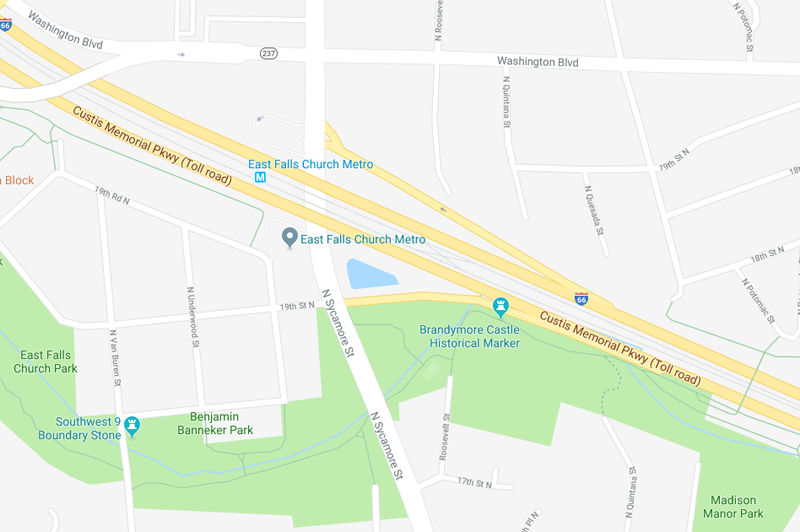

Parker was engaged in numerous Arlington civic organizations following his move to the County, including the Nauck Citizens Association and Arlingtonians for a Better County. On November 21, 1959, Parker became the first African American appointed to Arlington County’s Planning Commission and served as its first African American chairman in 1962 and 1963. He served at least two subsequent terms and chaired the Planning Commission’s Capital Improvements Committee. Much of this time included the hotly debated statewide discussion about building I-66 across northern Virginia and through Arlington into Washington, D.C.

Parker did much to promote the overall welfare of Arlington County during his tenure on the Planning Commission and through his service on numerous local boards and committees. In his civic work, Parker also championed the built environment and educational opportunities in the historically African American communities of Arlington. His efforts included preventing the construction of the proposed “Southside Freeway” that would have displaced African American businesses and homeowners, and fighting the proposed rezoning of Green Valley’s business district that would have made the area completely residential.

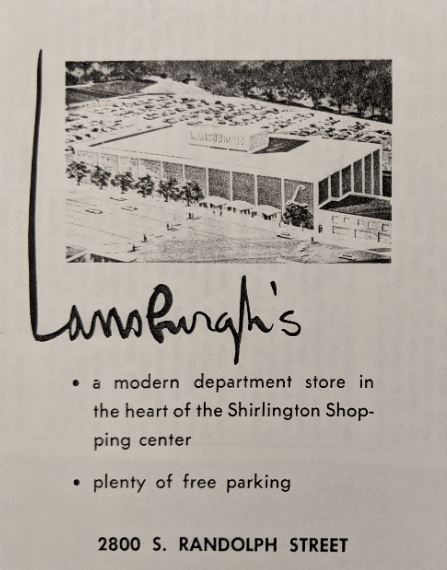

In our Rediscover Shirlington blog post, there was mention of the proposed suggestion to build a parallel shopping center to the Shirlington Business Center to provide facilities available to customers of color. Parker, as chairman of the Nauck Citizens Association, spoke to The Washington Post about how this proposed development was not meant to detract from desegregation efforts but instead provide needed services to the African American community until desegregation provided all Arlingtonians with equal access to resources.

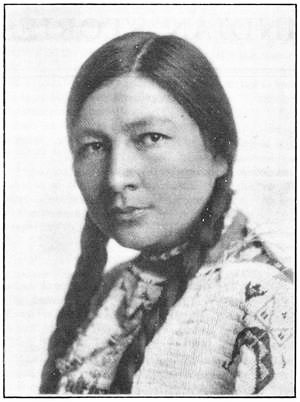

Photo of Lutrelle Fleming Parker Sr. Image courtesy of Arlington National Cemetery Website.

Parker also petitioned the Arlington School Board to address persisting inequities between Arlington’s traditionally white and black public schools following their 1959 desegregation. Thanks to his outstanding work in education policy and his time working with the PTA for the Hoffman-Boston and Drew-Kemper schools, Parker was on the list of potential candidates for the Arlington School Board in 1970.

Parker’s long list of professional and civic accomplishments includes Judge on the Court of Patent Appeals, Secretary of the Board of Trustees at Arlington Hospital, President and Board Chairman of the National Capital Area Hospital Council, Board Chairman for the George Mason University Foundation, and member of the Virginia State Council of Higher Education. We recognize Lutrelle Fleming Parker, Sr., for his decades of service to Arlington and to the generations of residents whose lives are improved thanks to his civic dedication.

"Preservation Today: Rediscovering Arlington" is a partnership between the Arlington Public Library and the Arlington County Historic Preservation Program.

Preservation Today: Rediscovering Arlington

Stories from Arlington’s Historic Preservation Program

Arlington’s heritage is a diverse fabric, where people, places, and moments are knitted together into the physical and social landscape of the County.

Arlington County’s Historic Preservation Program is dedicated to protecting this heritage and inspiring placemaking by uncovering and recognizing all these elements in Arlington’s history.

To learn more about historic sites in Arlington, visit the Arlington County Historic Preservation Program.