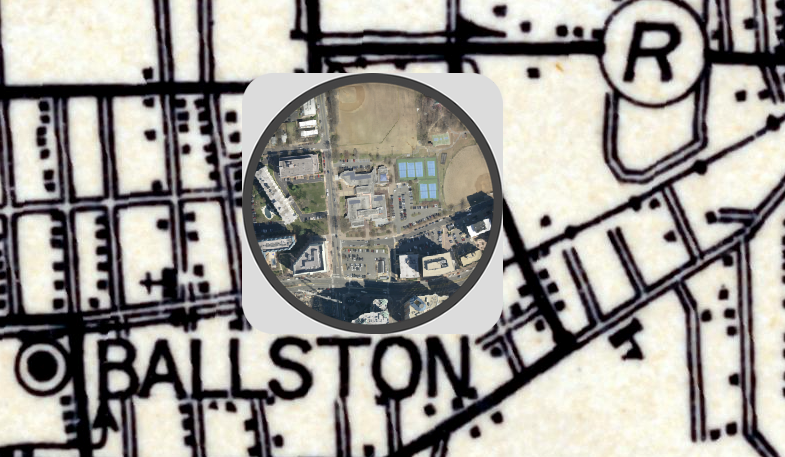

Arlington is currently in the process of changing its iconography. Let's take a look back at the previous versions of the Arlington Logo as the County begins the process of updating its visual identity.

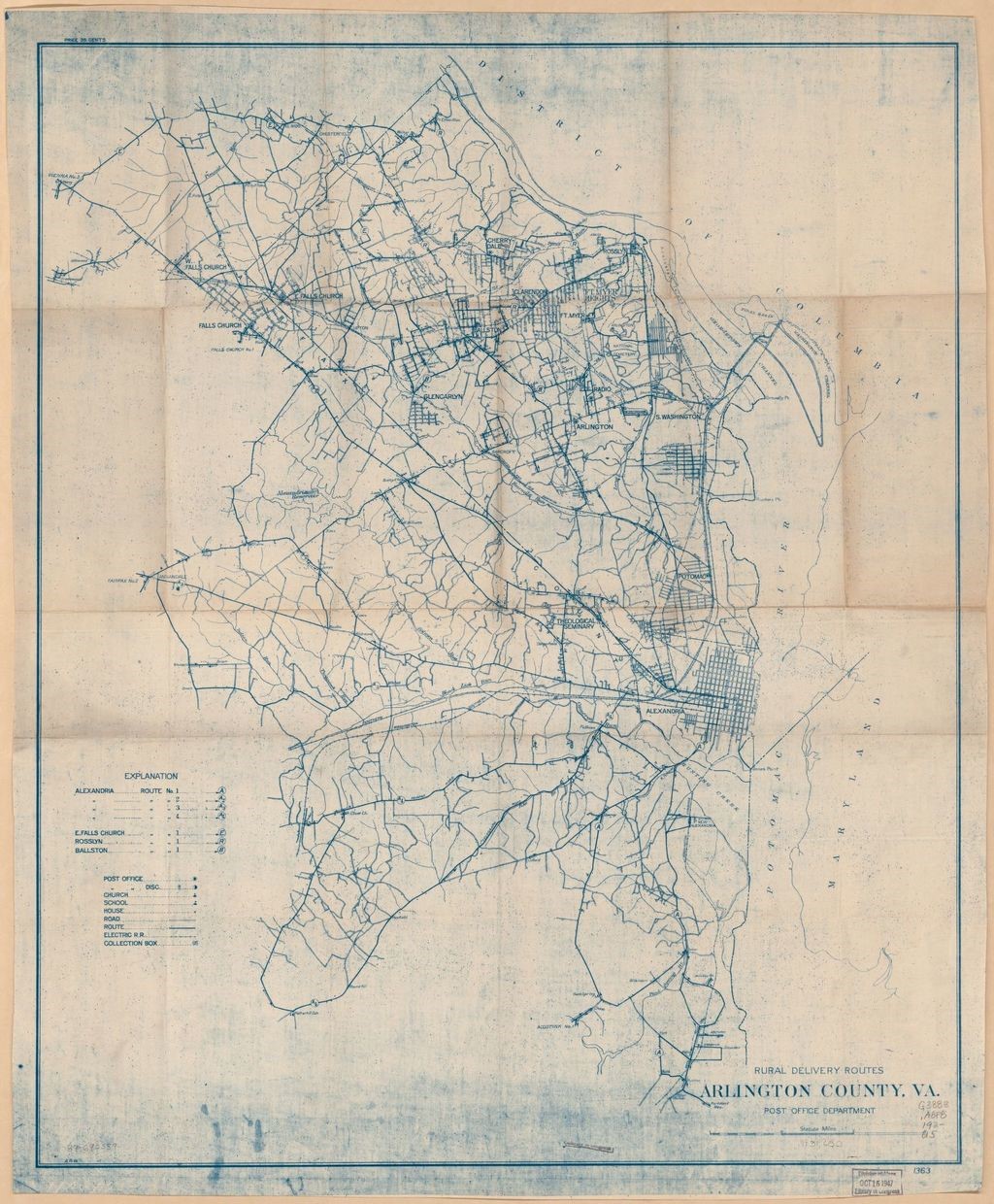

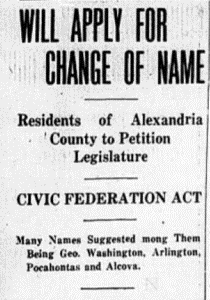

Arlington County was formally designated in 1920, changing its name from Alexandria County in order to distinguish itself from the nearby City of Alexandria. The County initially used the Virginia state seal in official documents, which depicts the Roman goddess Virtus conquering Tyranny. It is accompanied by Virginia's state motto, “Sic Semper Tyrannis,” or “Thus Always to Tyrants.”

Arlington House

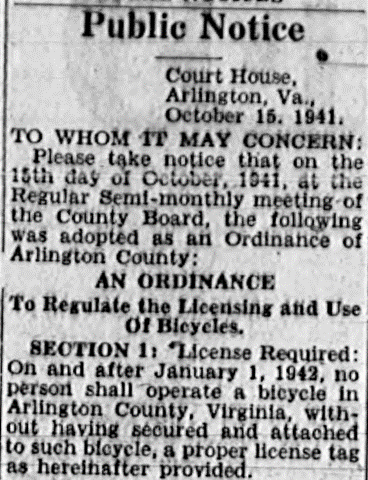

Around the mid-1960s, Arlington began using an unofficial County seal. However, the Commonwealth’s Attorney decided that the County Board did not have the authority to adopt a seal. The County Board subsequently authorized the use of a visual signature on documentation, but in 1969 declined to make it a seal based on this legal guidance. Because of this designation, then-County Manager Vernon Ford described the seal as a “decorative medallion.”

The unofficial seal featured Arlington House and the date 1801 in later versions. This was contested by Arlington history expert Eleanor Templeman. The date was chosen to represent the formal establishment of the County of Alexandria, but Templeman argued that it could be incorrectly interpreted as the date of construction of Arlington House, which commenced in 1802. The 1801 date prevailed, however, remaining on the County seal into the 1980s.

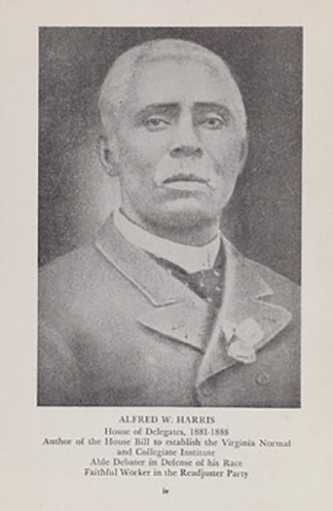

The main image on the seal, Arlington House, was the longtime home of Robert E. Lee, leader of the Confederate Army. The building was constructed by slave labor for George Washington Parke Custis, who was George Washington’s step-grandson and Lee’s father-in-law. After the start of the Civil War, the Lee family fled and the property was used by Union troops as a burial site, and the location would eventually become part of Arlington National Cemetery.

Since 1972, the site has formally been known as “Arlington House, the Robert E. Lee Memorial,” reinstating its ties to the Confederate leader. In 2020, legislation was proposed to remove Lee’s name from the historical site, citing the erasure of Black Americans who lived in slavery on the property.

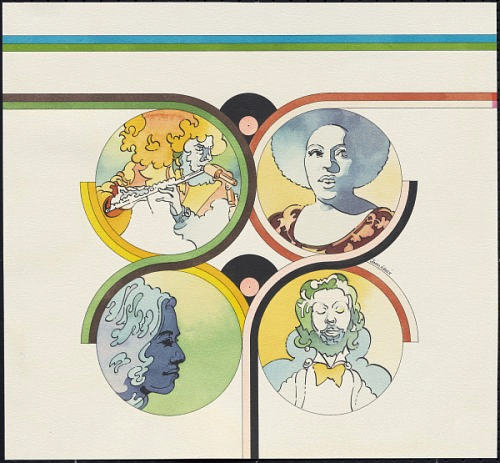

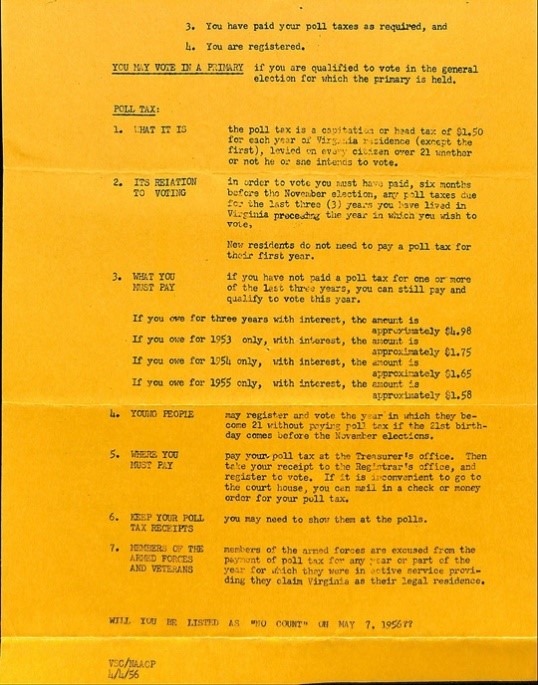

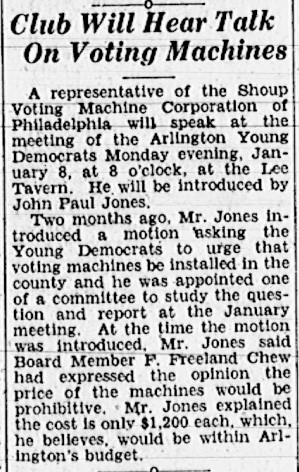

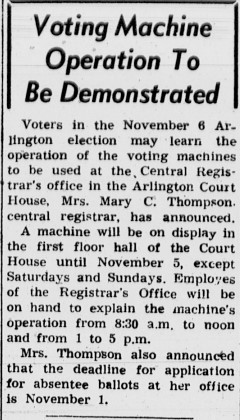

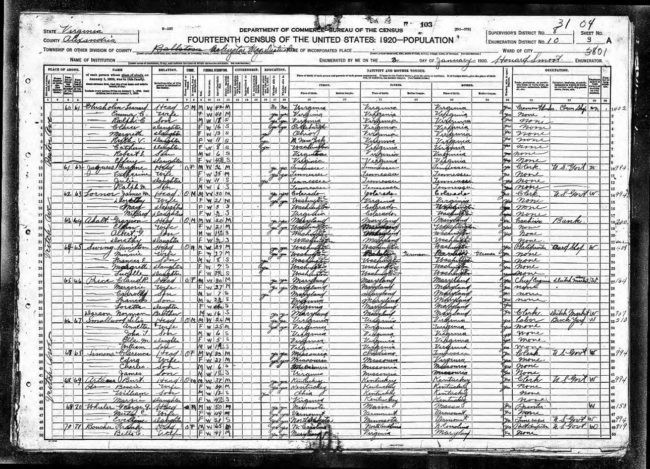

Examples of use of the state seal and unofficial County seal, from 1974 and 1976.

The "A" Logo

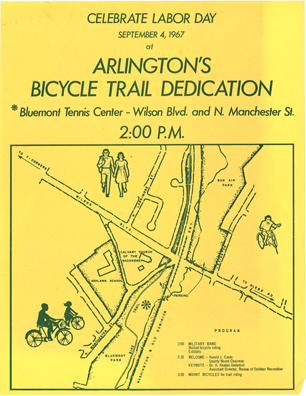

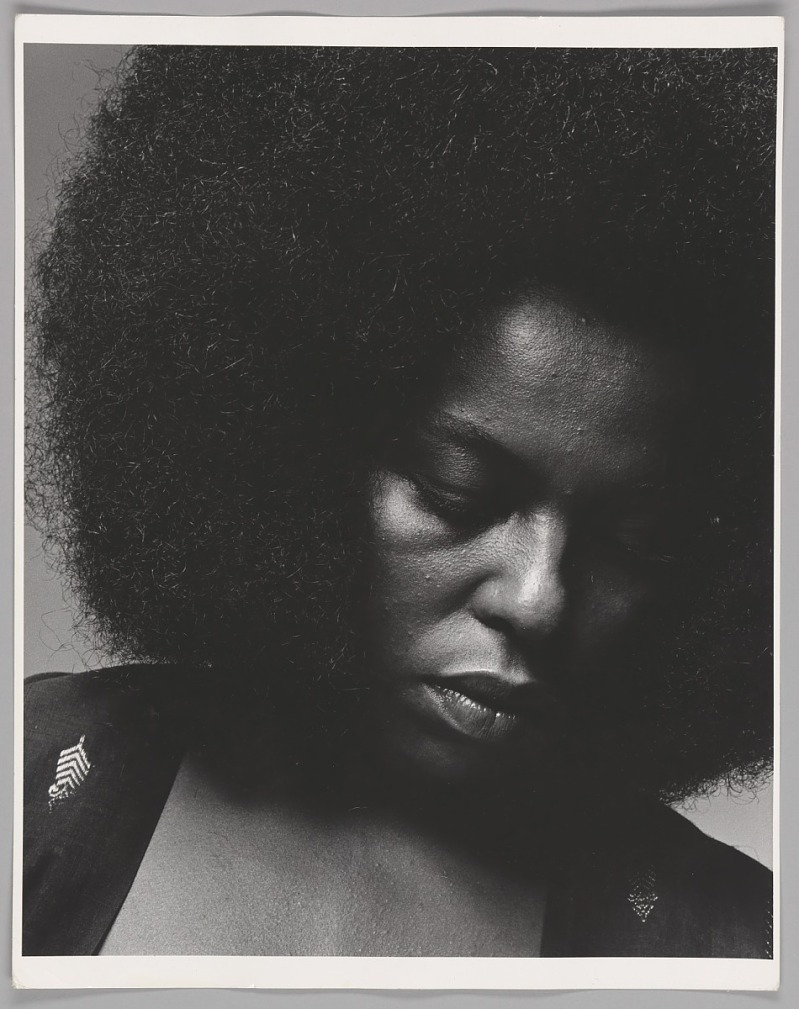

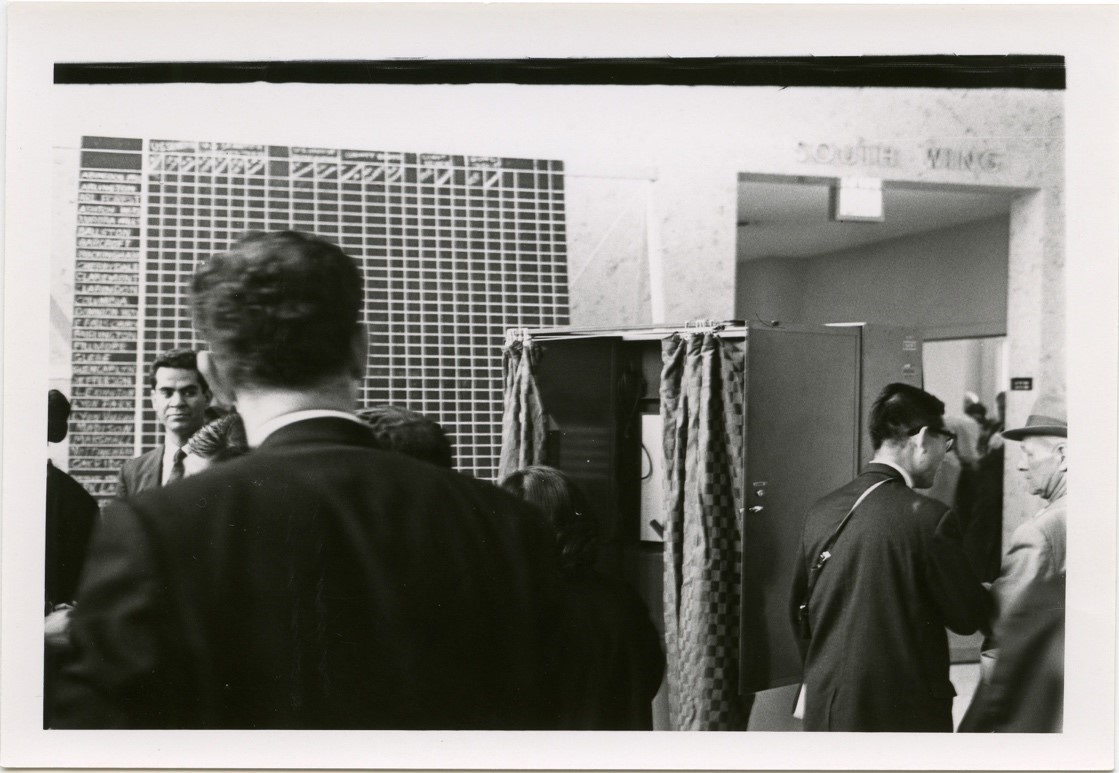

In 1976, the County began using an unofficial logo in the form of a stylized “A,” with Arlington House also appearing on this image. The logo was designed by Susan Neighbors, a professional illustrator from Arlington, who produced five designs based on County guidance. These options were then voted on by the public at ballot boxes placed at the County libraries, and the “A” logo won the contest.

County Flag Design

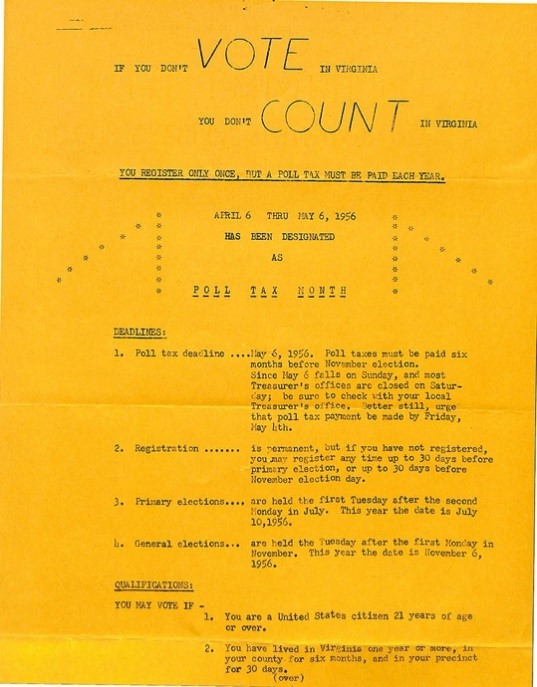

In September 1982, the County set out to adopt an official design for the County flag, and the County Board adopted a resolution for a flag design competition and a Flag Selection Panel to choose the design. In March of 1983, the County released a call for entries for the design of the flag to the public. Design requirements included the use of blue and white colors, and the words “Arlington County, Virginia,” as well as “1920.”

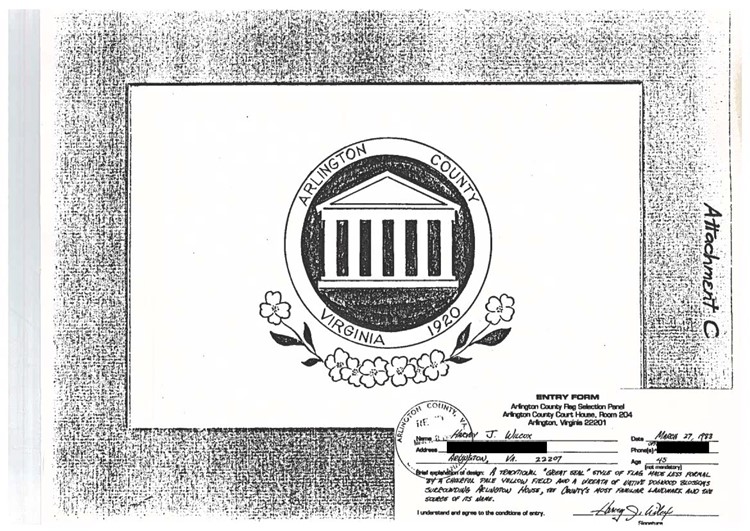

One hundred and ten people submitted designs for the contest, and Harvey J. Wilcox was selected as the winner in April of 1983. Wilcox, a deputy general counsel for the Navy, had no formal design experience and came up with the design while homebound with the flu. His imagery reflected the County’s unofficial logo and seal with a depiction of Arlington House, accompanied by a white ring and sprays of dogwoods underneath. Yellow was chosen as the background color for the flag.

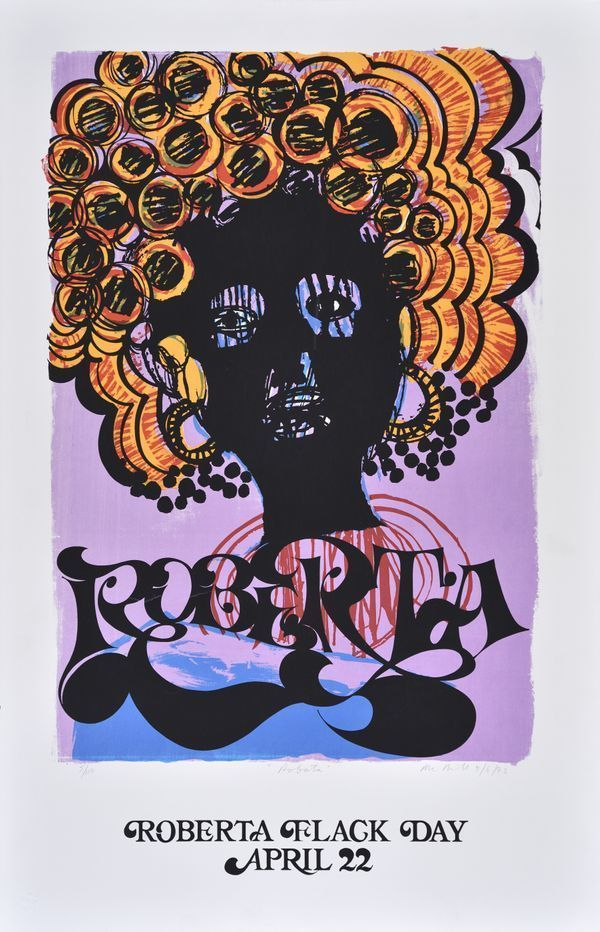

Harvey Wilcox’s winning entry for the 1983 design contest.

After consulting with the Virginia Attorney General, who issued a different opinion than the one about 20 years prior, the County’s authority to have a flag was dependent on the County having a seal. So, Wilcox’s design then became the County seal, which would subsequently be presented on the County flag.

The inclusion of “1920” from the original design rules was also dropped for the final iteration, due in part to the issues that were raised by Templeman decades before. One of the issues was Arlington had multiple dates in its history that could be considered as equally significant in its history. The County seal and flag were officially adopted on June 18, 1983.

Examples of the new County seal on official documents and letterhead. Images from 1994 and the late 1990s.

The Future of the Logo

The next major step in Arlington’s formal iconography was when the County created and adopted an official logo in 2004. The logo came along with a redesign of the County website that same year and was designed by the D.C. office of Gensler Studio 585. Focus groups were held with design professionals, members of the business community, and members of the general public.

The resulting design was adopted in the summer of 2004, and, like the County seal, included a stylized representation of Arlington House, but the design drew some criticism. In a public poll of more than 1,000 responses conducted by the Arlington Sun Gazette, 81 percent opposed the new design, 15 percent supported it and 3 percent voted, 'it's OK, I guess.’ In October 2004, a petition was circulated calling for the removal of the logo, and it “even inspired a piece of folk art by an artist, who rendered the new logo in dead cicada shells."

Arlington County’s logo, adopted in 2004.

The County seal and logo were then used concurrently, but for different outlined purposes. In general, the seal is used for items relating to the County Board and for more permanent items (such as the County flag, permanent signage, and certificates).

The logo is considered a marketing sign and is used on departmental materials (such as County vehicles and general correspondence). In 2007, the County sought public comment and issued an update to the seal due to persistent inconsistencies in its rendering. The update kept the same imagery on the seal, but restored the original “Arlington blue” and refined it for online use.

In September 2020, the County announced that it would adopt a process to develop a new logo and seal, moving away from imagery related to Arlington House in County iconography. In January 2021, a Logo Review Panel was assembled to review concept submissions from the community, and in April announced five options selected from a pool of more than 250 ideas.

A pre-2007 graphic file of the County seal and the updated version, which is still in use today.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Charlie Clark Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields