The Organized Women Voters of Arlington was founded in 1923, just three years after the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution extended the right to vote to women.

A decidedly non-partisan organization, the OWV was unique in its distinct attention to matters facing the County. In an interview with the Northern Virginia Sun in 1958, then-president Ms. Woolley stated she believed “that the Organized Women Voters of Arlington is the only women voters’ group in the United States that is concerned solely with matters of local interest.”

While the OWV’s objective was to “collect and disseminate political and civic information,” it also served an important role as a space for the improvement of women’s social position within the county. Many prominent female leaders from Arlington, including county board members and former state senator Mary Margaret Whipple, have been a part of this significant organization.

In an oral history recorded in 1983, former OWV President Mrs. Sue Renfro remembered a time early on in the organization’s history when the two functions of education and political support intersected:

“At the first meeting there was a Sheriff Fields that came to speak to the ladies since they were having the vote. And he promised them that he would do something for them, so they asked him would he be willing to make an appointment [appoint a woman, and he replied] “Well, yes, under the circumstances.”

So then they had the election. Sheriff Fields won, and he just seemed to forget about appointing a lady. And the ladies decided that they should go and inspect the jail.

So they made several trips to inspect the jail, and finally it was reported that the sheriff looked up one day and saw the committee coming again to inspect the jail and decided that he might just appoint one of them, and he appointed Mrs. Pauline Duncan.

… She was the first deputy woman sheriff in the Commonwealth of Virginia.”

In the photo above, attendees gather at the OWV’s 31st birthday luncheon in 1954.

These were high-profile events for the organization, and every year the group named a “Woman of the Year” from Arlington County. In 1938, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was an honored guest. Today, the Organized Women Voters still meets on the 4th Tuesday of every month from September through May at Essy’s Carriage House, to hear from candidates and county representatives.

Thank you to current president Nancy Renfro for the information regarding the organization’s current activities.

Learn More from the Center for Local History at the Central Library.

You can request to view materials in person from Record Group 17 – Records of The Organized Women Voters of Arlington County – or read the full interview excerpted above with Sue Renfro and Lillian Simms, cataloged as VA 975.5295 A7243oh ser.3 no.215.

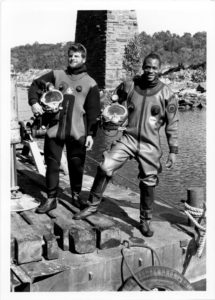

In the exhibit we asked visitors to guess what these two Arlington County employees were getting ready to do.

In the exhibit we asked visitors to guess what these two Arlington County employees were getting ready to do.

Virginia in Postcards contains 80 postcards from the Eastman-Fenwick Family Papers and the personal postcard collection of Diane Salman. These have been digitized, both front and back (or recto and verso, as archivists sometimes call them) for a total of 160 images.

Virginia in Postcards contains 80 postcards from the Eastman-Fenwick Family Papers and the personal postcard collection of Diane Salman. These have been digitized, both front and back (or recto and verso, as archivists sometimes call them) for a total of 160 images.