Join us for a new series of stories from the Center for Local History highlighting members of our community who made a difference in ways that helped shape our history and created positive change.

Their voices were not always loud, but what they said or did had a significant impact on our community.

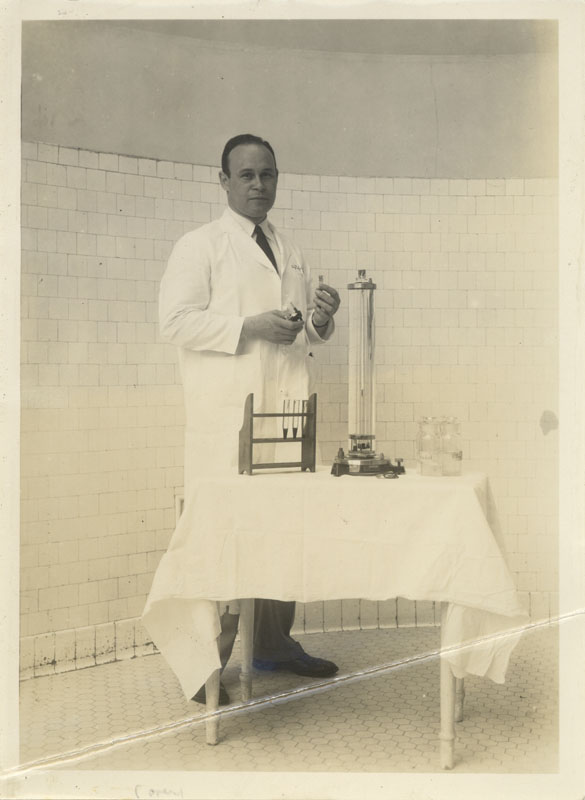

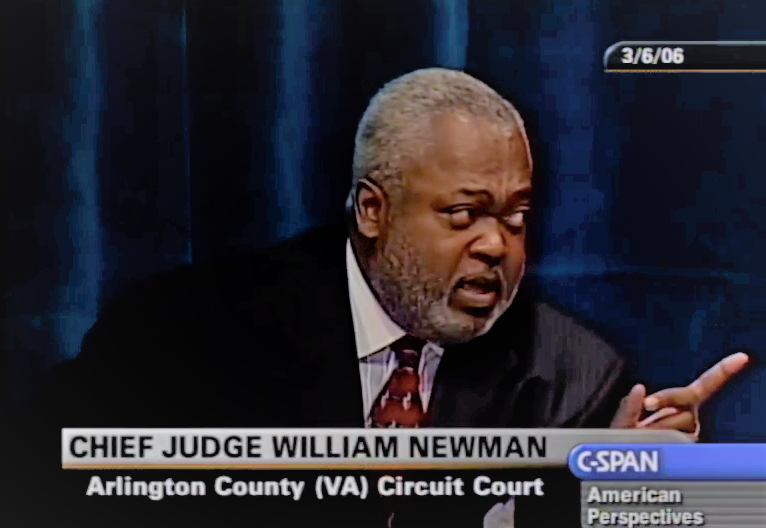

Dr. Charles Drew

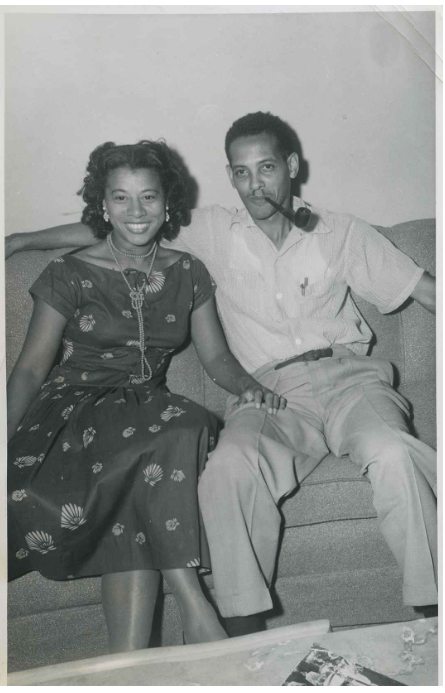

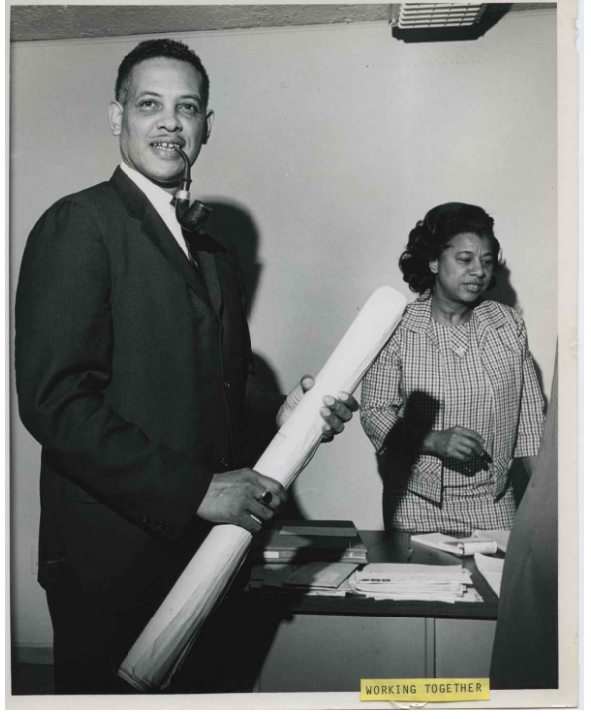

Dr. Charles Richard Drew (1904-1950) was a surgeon and a pioneer in the field of blood plasma preservation, storage, and transfusions. His accomplishments as the creator of the modern-day blood bank came during a time when opportunities for minorities in the medical field were nearly non-existent and society at large was beset with racial division and prejudice.

Born in Washington D.C., Drew arrived in Arlington County in 1920 when his parents relocated to what is now known as the Penrose neighborhood, although he continued to attend the District’s Dunbar High School. Awarded an athletic scholarship by Amherst University in Massachusetts, he graduated and subsequently gained employment at Morgan College in Baltimore, Maryland. From 1926–1928, he was a professor of chemistry and biology, served as football coach, and was the first athletic director at the historically Black institution.

Using the money he saved from his tenure at Morgan College, Drew studied medicine at McGill University in Montreal, Quebec, finishing second in his class while earning his Doctor of Medicine and Master of Surgery degree in 1933. Following a brief time spent as a faculty instructor for pathology at Howard University and teaching surgery/assistant surgeon at Freedman's Hospital, in 1938 Drew undertook graduate and then postgraduate studies at Columbia University in New York City. This marked the genesis of Drew’s groundbreaking research, authoring his seminal dissertation "Banked Blood: A Study in Blood Preservation”, which his mentor Dr. John Scudder described as “a masterpiece” and “one of the most distinguished essays ever written, both in form and content.”

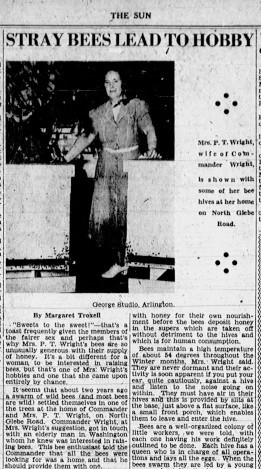

Home of Dr. Charles Drew in the now Penrose Neighborhood in Arlington County

In 1940, he became the first Black to earn a Doctor of Science degree in medicine before traveling to New York City, where he headed the World War II-era “Blood for Britain” program. “Blood for Britain” used Drew’s research in the field of blood plasma to enable the preservation, storage, transport, and distribution of donated blood from United States donors to British soldiers and civilians. The program also ushered in the use of “bloodmobiles”, a means by which refrigerated containers of stored blood were transported by trucks and vans to hospitals, clinics, and individuals in need.

In 1941, Drew became director of the American Red Cross Blood Bank but resigned from the position a year later, following a pronouncement by the armed forces that the donated blood of African-Americans would be stored separately from those of whites. This 1944 quote reflects Drew’s feelings:

"It is fundamentally wrong for any great nation to willfully discriminate against such a large group of its people…One can say quite truthfully that on the battlefields nobody is very interested in where the plasma comes from when they are hurt…It is unfortunate that such a worthwhile and scientific bit of work should have been hampered by such stupidity."

Drew then returned to Howard University and Freedmen’s Hospital where he taught and performed numerous surgeries.

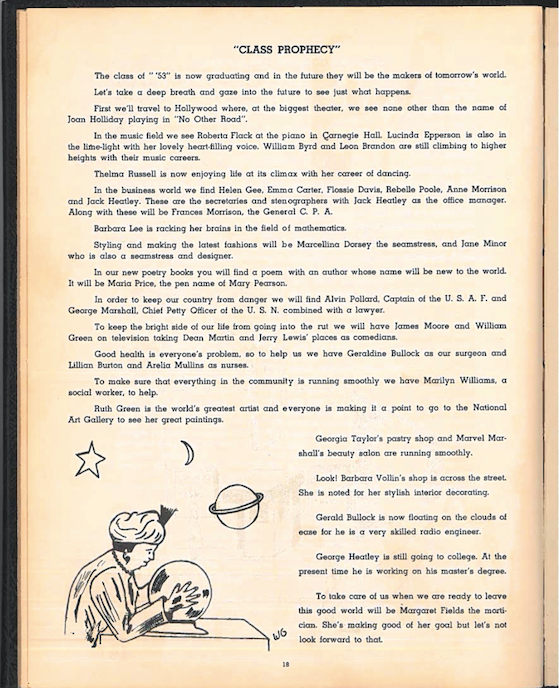

Dr. Charles Drew

On April 1, 1950, during a visit to Tuskegee, Alabama where he attended the annual free clinic at the John A. Andrew Memorial Hospital, Drew was involved in a tragic automobile accident. The accident was a result of exhaustion and fatigue after spending the previous evening performing operations and surgeries.

The accident caused his three passengers only minor injuries, but Drew’s were severe and proved to be fatal. Drew passed away that same day, and his funeral was held on April 5, 1950, at the Nineteenth Street Baptist Church in Washington, D.C.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Charlie Clark Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields