Join us for a new series of stories from the Center for Local History highlighting members of our community who made a difference in ways that helped shape our history and created positive change.

Their voices were not always loud, but what they said or did had a significant impact on our community.

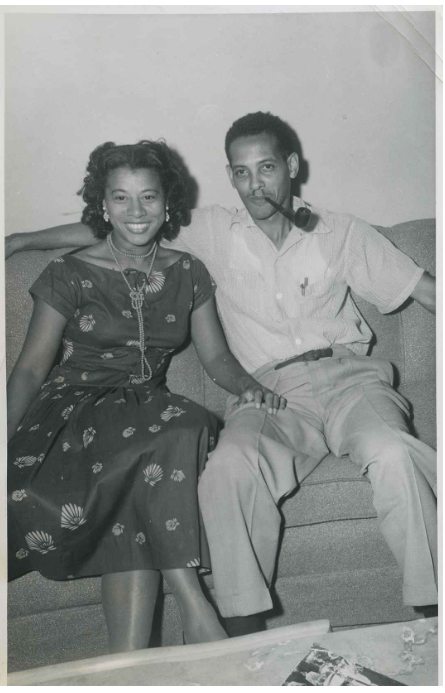

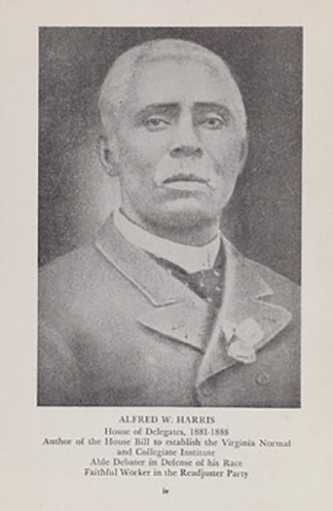

William A. Rowe

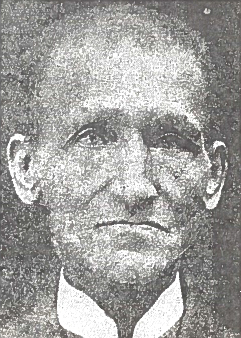

William Augustus Rowe (1834-1907) was a pivotal figure in the early development of the Green Valley/Nauck community. In the face of a post-Civil War world in which the Emancipation Proclamation was more legal decree than societal reality, Rowe persevered to achieve many firsts as a Black policeman, politician, elected official, district Supervisor and Chairman, and community leader.

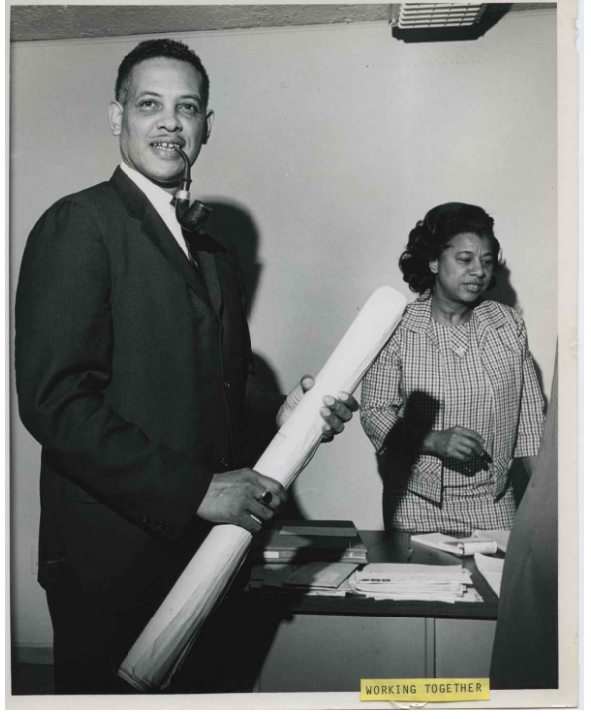

William A. Rowe, possibly 1880's

Born into enslavement around 1834, Rowe eventually escaped and settled in the Freedman’s Village community. There, he trained and became a skilled blacksmith prior to becoming the first Black policeman in Arlington County. Rowe soon proved himself to be an able and effective politician, becoming the first Black elected to the Board of Supervisors. He served as Supervisor of the Jefferson District from 1871 to 1879 and as Arlington District Board Chairman from 1879 to 1883 after moving to Green Valley/Nauck, where he had previously purchased 5 acres of land from Sewell Corbett.

Upon Rowe’s departure from the Jefferson District, he earned this extraordinary resolution from the other two white supervisors:

“Resolved that the resignation of William A. Rowe as a member of this board having been made known, the faithful and efficient discharge of his duties during the past ten years, and the upright and honorable conduct that has marked his public service entitles him to the confidence, esteem, and gratitude of the people of this County.”

William A. Rowe’s tenure with the Board of Supervisors is as follows:

- July 1, 1871-June 30, 1872, Jefferson Township, Board of Supervisors

- July 1, 1872- June 30, 1873, Jefferson Township, Chairman, Board of Supervisors

- July 1, 1873- June 30, 1874, Jefferson Township, “President” (Chairman), Board of Supervisors

- July 1, 1874- April 2, 1879, Jefferson District, Chairman (moved from Jefferson to Arlington District)

- July 1, 1879- June 30, 1883, Arlington District, Chairman

After his resignation as Chairman in 1883, he was appointed Superintendent of the Poor, a position he held through June of 1886.

Rowe continued to live in Green Valley/Nauck, where his son George served as a deacon at Lomax AME Zion Church, until his passing on December 5, 1907.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields