Arlington-based Native American artist and educator

Oral histories are used to understand historical events, actors, and movements from the point of view of real people’s personal experiences.

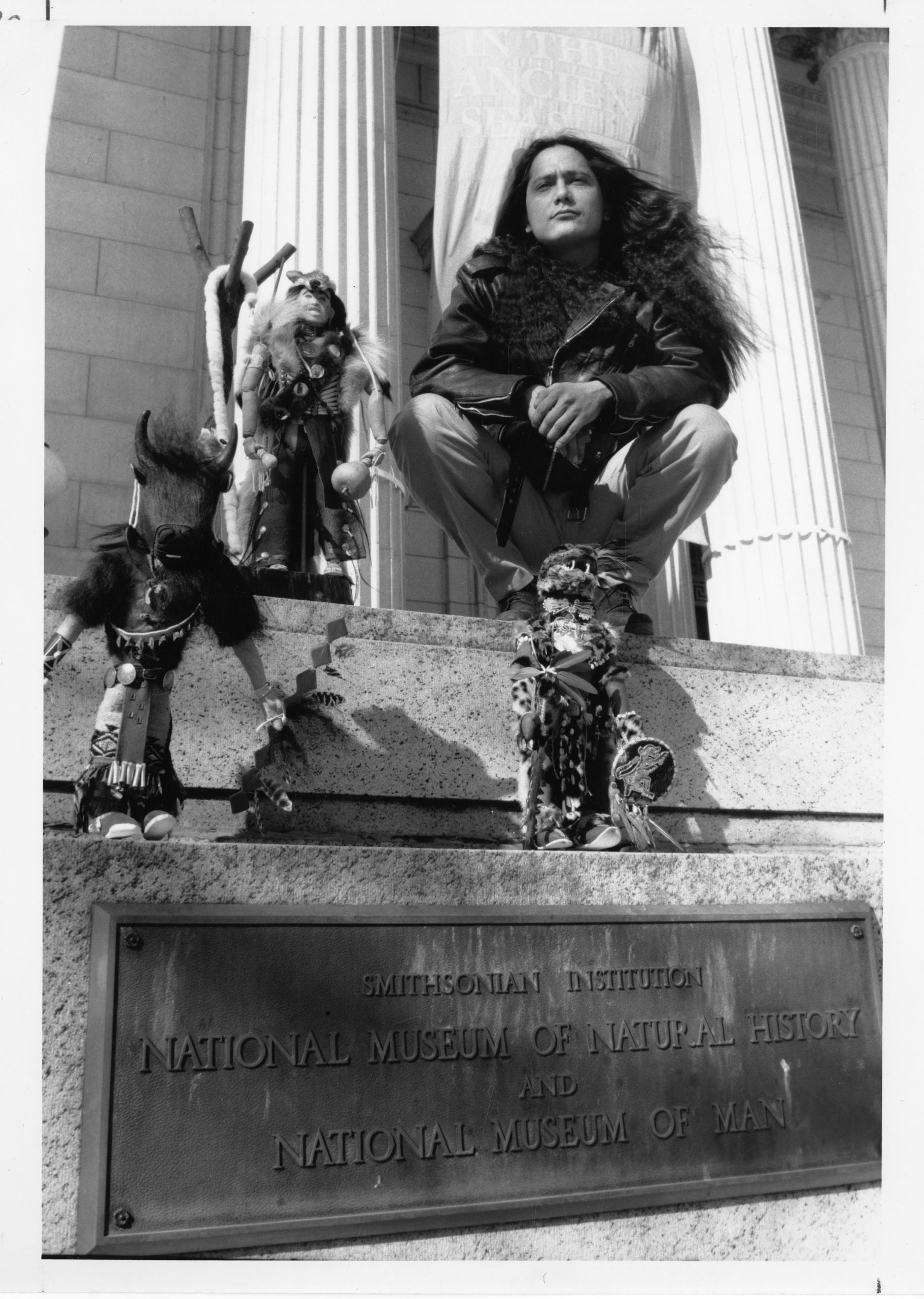

Artist Don Tenoso is a prolific creator, known for his Lakota-style dollmaking that depicts Sioux culture. Tenoso came to the Washington, D.C., area in 1991 as the first artist-in-residence at the Smithsonian’s Natural History Museum, where he created new pieces and led demonstrations for the public.

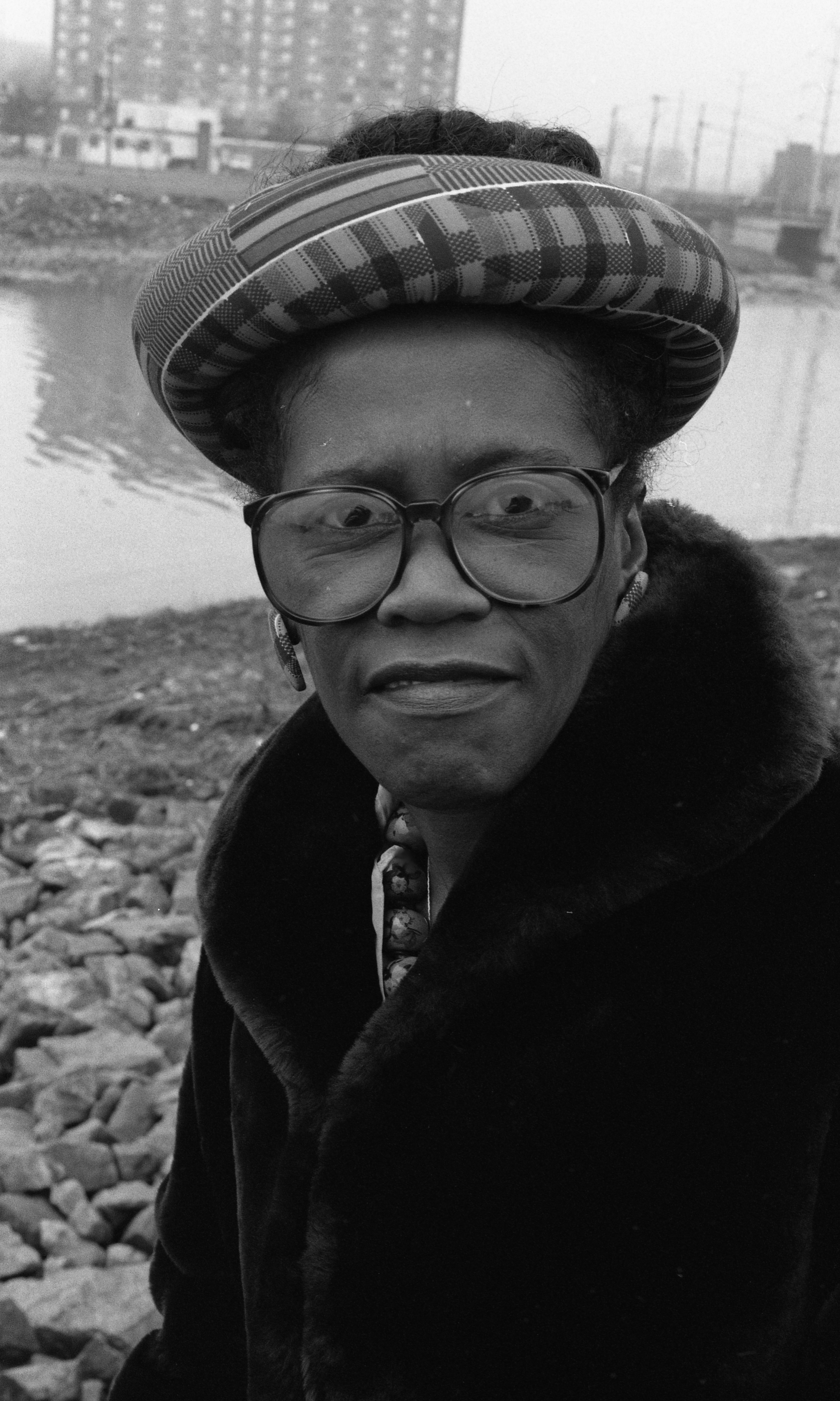

Don Tenoso, circa 1990 at the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

Tenoso was born in Riverside, California, and is a member of the Hunkpapa, one of the seven bands of the Teton Lakota Nation and part of the Sioux-speaking indigenous population. Tenoso’s mother was born on the Standing Rock reservation in South Dakota, and he is a descendant of One Bull and Sitting Bull. His father was in the U.S. military during Tenoso’s early life and the family often moved around the country and abroad.

The following interview excerpts are from a 2008 oral history with Tenoso. At the time of this interview, he had lived in Arlington for about 14 years. In the full interview, which can be accessed in print at the Center for Local History, Tenoso also discusses his family and lineage, as well as tribal traditions and the Lakota language.

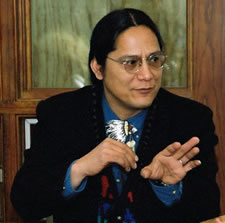

Don Tenoso, circa 2005. Image courtesy of the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, where Tenoso was the university’s first artist-in-residence at the Native American House.

Narrator: Don Tenoso

Interviewer: Tom Dickinson

Date: January 23, 2008

Note: The audio for this interview is currently unavailable.

Don Tenoso: I was the first artist-in-residence in the Natural History Museum. Prior to that they had brought me in for a three-day doll demonstration where they had taken one of the glass cases out of one of the Native halls there in Natural History at Smithsonian and by different artists coming in. Me, a Sioux doll maker, was invited to come up and do that. I guess they had spent like nine months trying to find me. I started dollmaking back in the seventies.

Anyway, in the eighties, ‘86 or so, ‘87, there was an article in American Indian Art magazine that was published about dolls. In ‘86 I believe it was, I had a one-man show down in Andrew Park, Oklahoma and they collected the International Crafts Board for four of my dolls.

So one of them got in that article and then the director over at education in the outreach program saw the doll and they said they wanted to find that guy.

Don Tenoso circa 1991 outside of the National Museum of Natural History with some of his works of art. The doll beside Tenoso is called “Iktorni,” or “trickster doll.” Image courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution Archives.

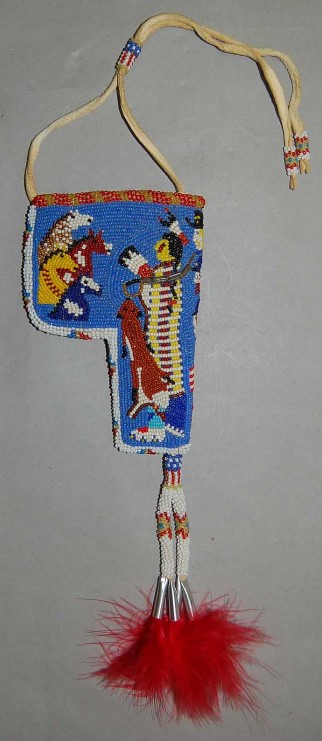

Leather holster created by Tenoso in 2006, covered in a beadwork design. Image courtesy of the British Museum, where the piece is held.

Tom Dickinson: How did you get started doing this [art practice]?

DT: Actually I started when I was in New York. I went out there because I heard that C. W. Post [campus of Long Island University] had a scholarship for Natives who wanted it to be teachers. It turns out they didn’t so I went to the American Indian Community House there in New York.

Actually, backpedal a little bit. I was born in Riverside, California in 1960. In ‘63 we were in France. We were there when de Gaulle kicked us out. So my earliest memories are there when the French high school kids were throwing rocks at us on the playground. They would stone our bus. I remember flying out of there and the U.S. piling up all these brand new, big boxes and stuff and just setting them on fire. Big old wrecking balls smashing holes into runways as you flew out. I also got to see some whales as we flew, that’s how low they went across the ocean. You can see the spouts and little tails going across.

So from there we go to Oklahoma City, so I got to meet all these Natives. They used to call it Indian Territory which is sort of a penal colony for Native Americans starting back through Trail of Tears, Andrew Jackson and all of that stuff.

From there we went and lived in Rapid [City] back where my grandma lived, lot of relatives in Rapid City, South Dakota, in the Black Hills which is our sacred area, which actually by federal courts is still our property. But they offered us $10 million or $100 million or something but we still don’t take it. Because our sacred Wind Cave is there and that’s one of our origin stories. We came from there. The thing about Wind Cave you stand there one hour of the day and it blows your hair back.

So geologists say, “Yeah, there’s probably an underground stream - they haven’t found it yet - flowing and air displacement and that’s causing your hair to go that way.” The only thing is you come back some hours later, same day, and now it’s sucking your hair into the cave. “I guess there’s a tilting rock or something under there that messes with it.” We say that’s Mother Earth breathing, that’s where she breathes from.

Learn more: View a program from the 1992 exhibit Contemporary Plains Indian Dolls, which took place at the Southern Plains Indian Museum and Crafts Center in Anadarko, Oklahoma. The exhibit featured a piece by Don Tenoso (“Gourd Clain Dancer,” figure 10).

This interview was conducted as part of The Many Faces of Arlington oral history project, which sought to document the County’s diverse population as a reflection on the 400th anniversary of the settlement of Jamestown by English colonizers.

The goal of the Arlington Voices project is to showcase the Center for Local History’s oral history collection in a publicly accessible and shareable way.

The Arlington Public Library began collecting oral histories of long-time residents in the 1970s, and since then the scope of the collection has expanded to capture the diverse voices of Arlington’s community. In 2016, staff members and volunteers recorded many additional hours of interviews, building the collection to 575 catalogued oral histories.

To browse our list of narrators indexed by interview subject, check out our community archive. To read a full transcript of an interview, visit the Center for Local History located at Central Library.