Arlington’s Libraries have been a mainstay of the county landscape for generations – but how did the library system as we know it come to be?

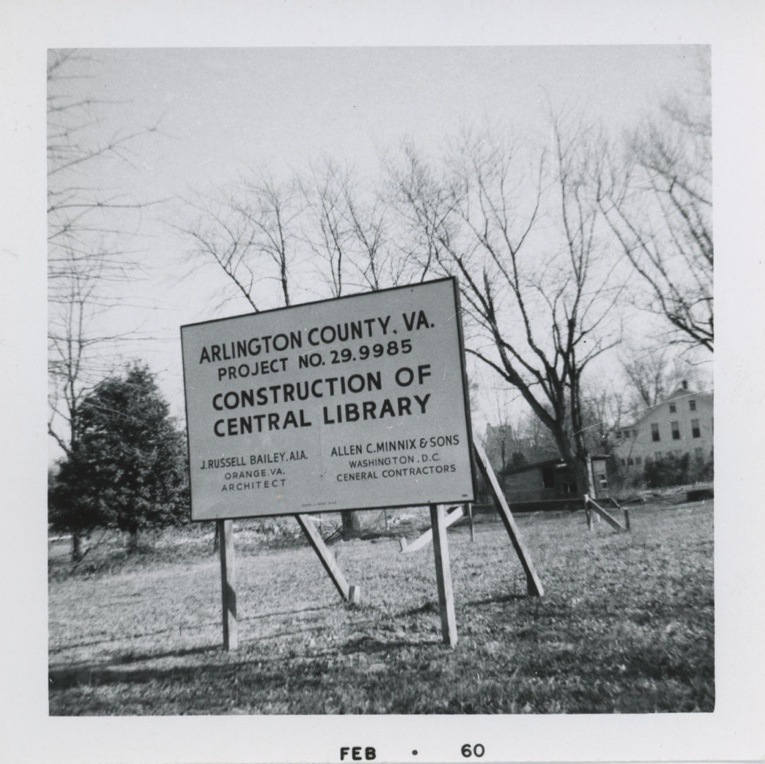

Construction signage for Arlington’s Central Library, February 1960.

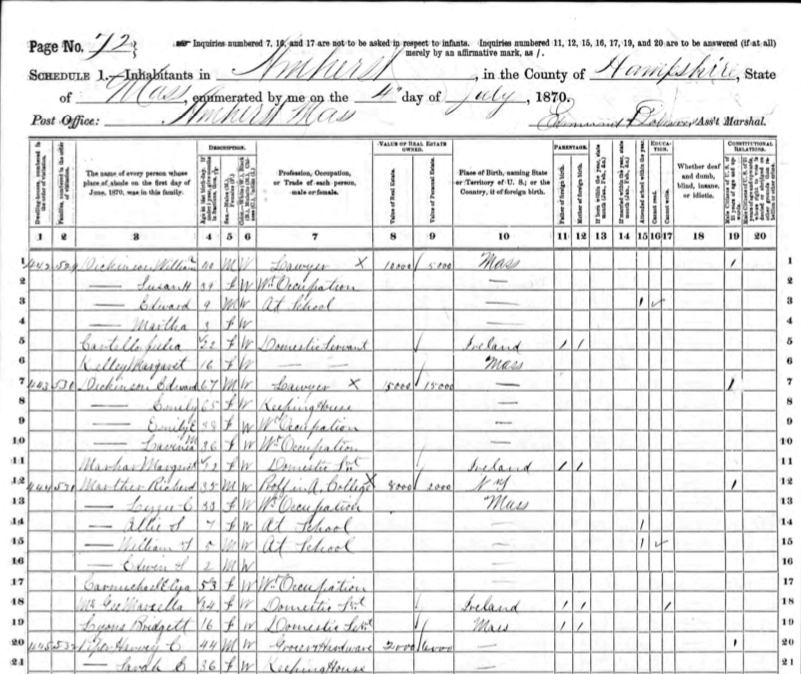

Before the year 1936, Arlington County had been served by five independent libraries: Glencarlyn, Cherrydale, Clarendon, Aurora Hills, and Arlington/Columbia Pike. These were volunteer-led efforts run independently rather than as a unilateral system, and that individually received limited financial support from the County. These locations were largely established and managed by women members of the Arlington community.

In 1936 however, the Public Library system changed forever. A group of citizens and representatives from those five libraries joined together to form a collective Countywide system and to appeal for increased County financial support. Four delegates from each branch as well as four delegates at large met to discuss the possibility of a cohesive, singular library system and what that would entail.

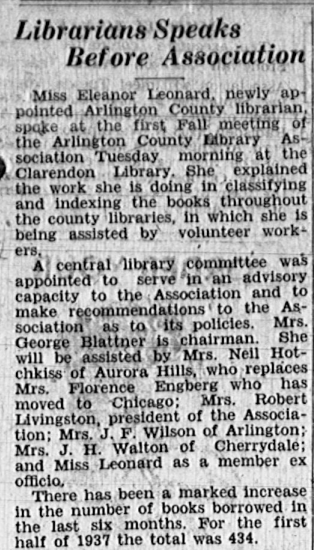

Articles from the Northern Virginia Sun describing the early efforts of Eleanor Leonard and the Arlington County Library Association. From September 17, 1937 (L), and November 11, 1937 (R).

A year later, in 1937, the newly formed Arlington County Library Association began work to establish Arlington’s first library system. In its early days, the Association completed a survey of the County’s libraries, population and resources to help guide their planning process. The group also conducted an “educate-your-county-officials” campaign, and eventually won their support. The County Manager at the time, Frank Hanrahan, agreed to their proposal under the condition that the proposed branches would need to meet ALA standards.

The group also voted unanimously to hire a professional librarian to oversee the formation of the library system. The County government later designated $3,500 to the libraries', $3,000 of which was for operational costs and $500 to pay the salary of the hired librarian.

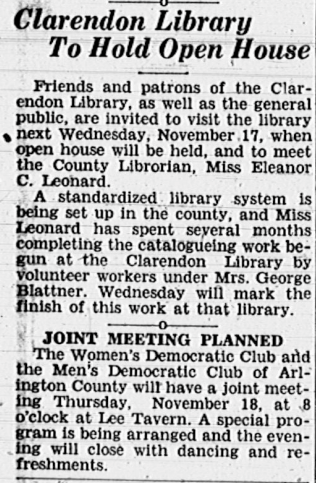

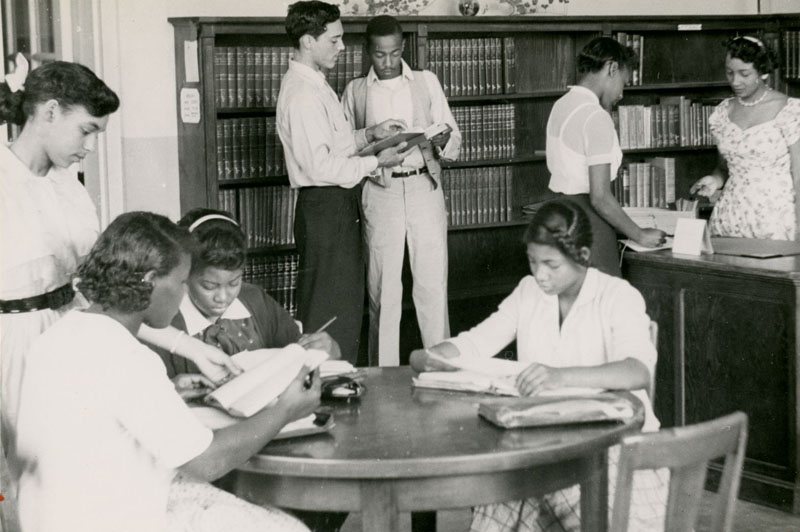

The Aurora Hills branch of the Arlington Public Library, July 1969.

In July of 1937, Eleanor Leonard was hired for the librarian position. Among her efforts to standardize and streamline the library system, she discarded damaged material, cataloged the library’s holdings, and trained volunteers in all aspects of library work. By the fall of 1939, the five libraries had been standardized, while the daily work of running the libraries continued to be done by volunteers. By July 1938, 11,328 books had been reclassified and cataloged according to American Library Association standards.

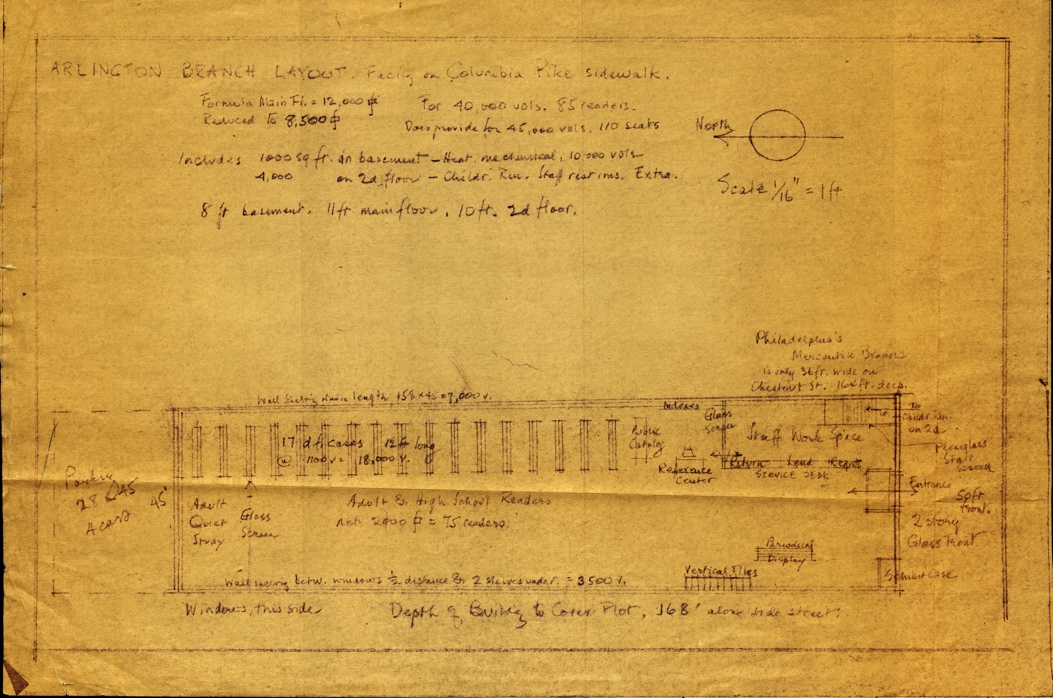

Architectural plans for the Columbia Pike Library, date unknown.

About a decade later, in 1949, eight branches were in operation, among them: Aurora Hills, Cherrydale, Clarendon, Columbia Pike, Glen Carlyn, Holmes, Shirlington (formerly Fairlington), and Westover branches.

The Holmes branch closed in 1949, and the Clarendon location became the Central Library, while the rest of the branches continue to stand where they are today, ready to serve their respective local communities again once the pandemic is over.

This post is a condensed version of the “Libraries” section of the Library’s Women’s Work project, featuring materials from RG 29: Arlington County Public Library Department Records.

To learn more about Arlington's history, visit the Center for Local History on the first floor of the Central Library.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields