Oral Histories with Michael Jones and Lance Newman

This Halloween came with hordes of masked and painted trick-or-treaters, tiny ghouls and monsters haunting Arlington’s doorsteps in search of candy. Although this ritual of begging door-to-door for sweets goes back centuries, “trick-or-treating" did not become a widespread phenomenon in the United States until the 1930s.

It wasn’t until after World War II, with the end of sugar rationing and the beginning of national marketing campaigns surrounding Halloween, that trick-or-treating became standard practice for children in cities and suburbs.

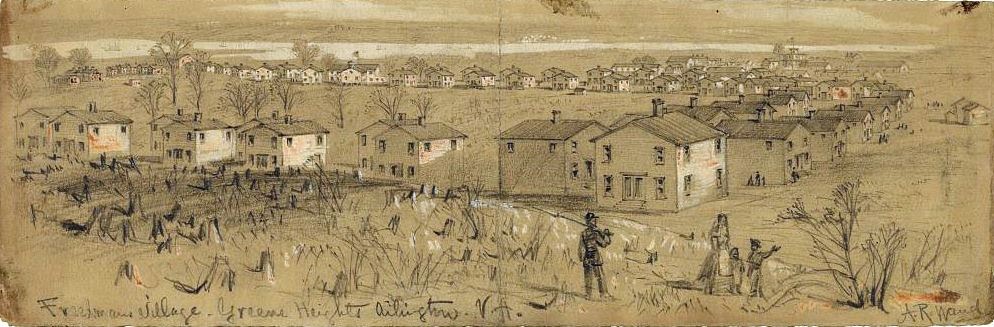

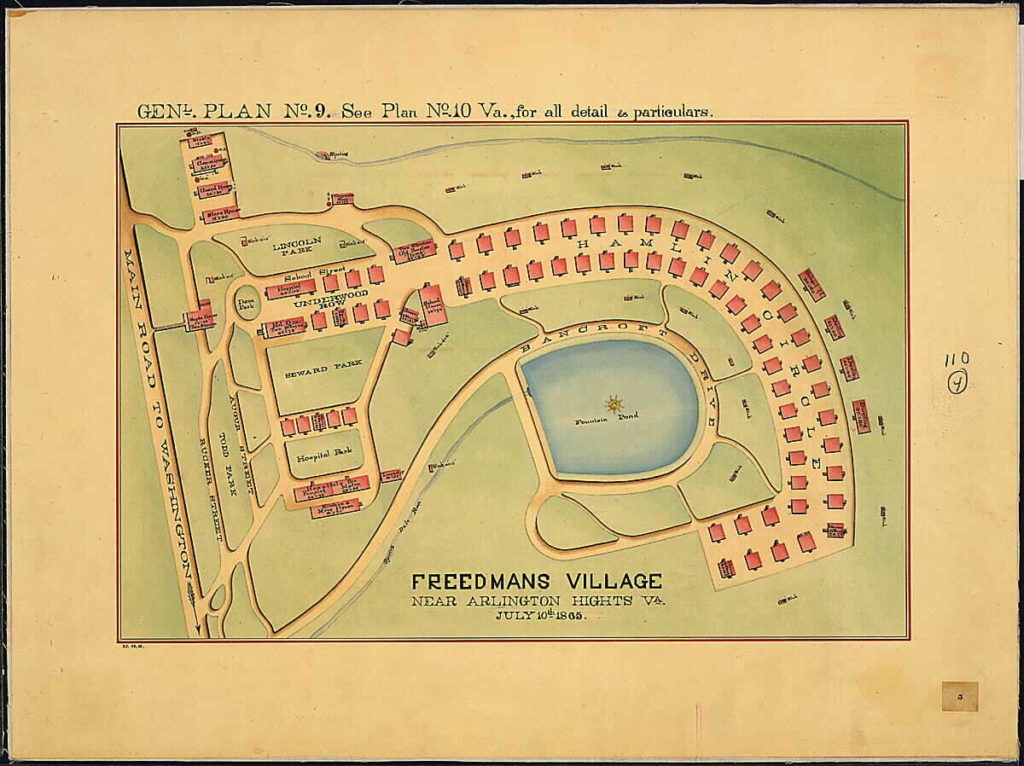

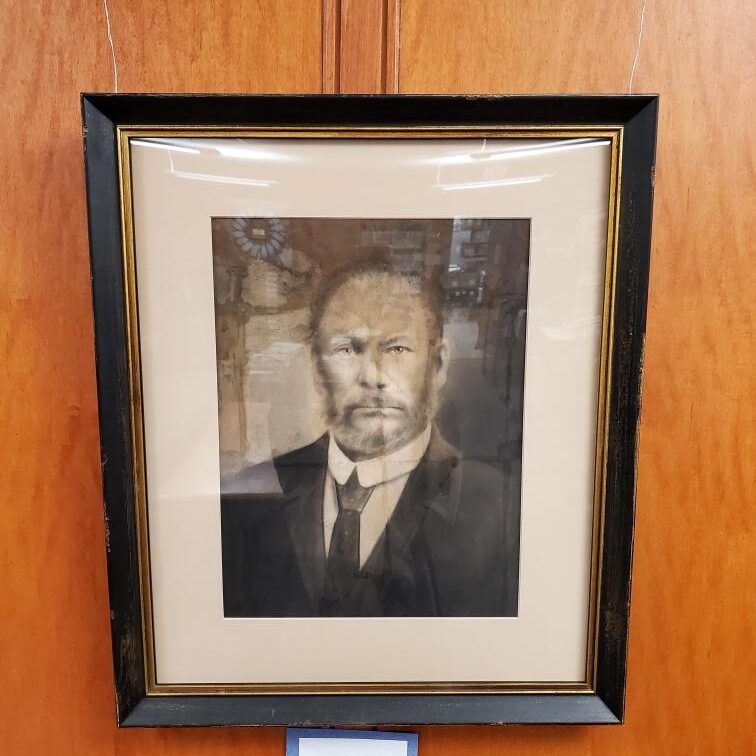

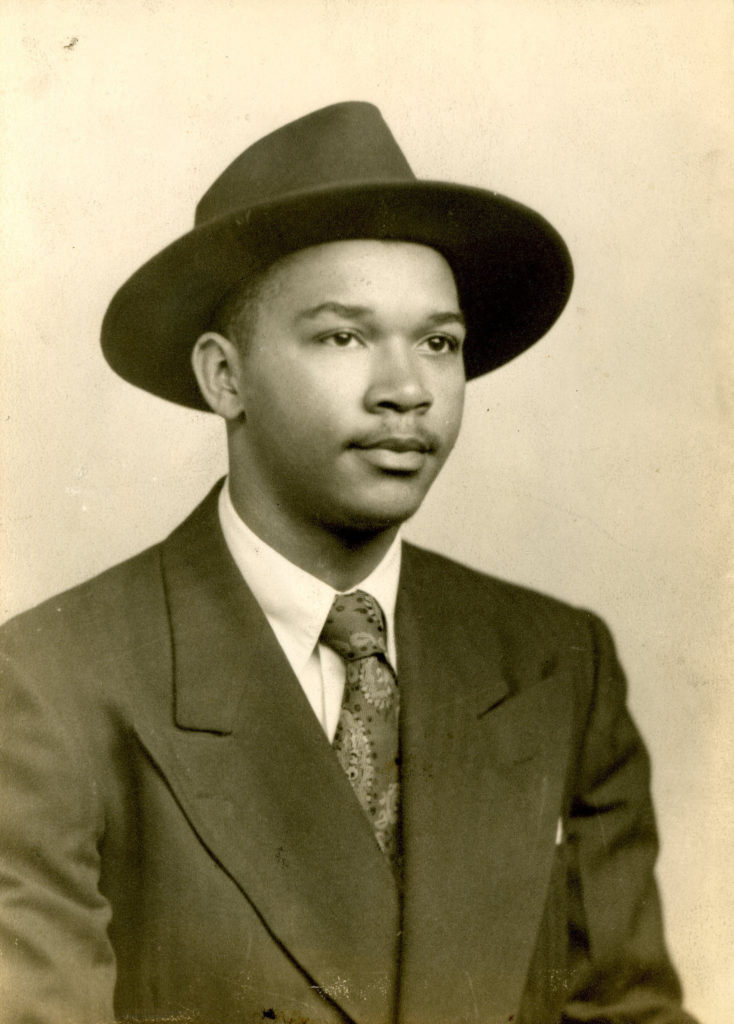

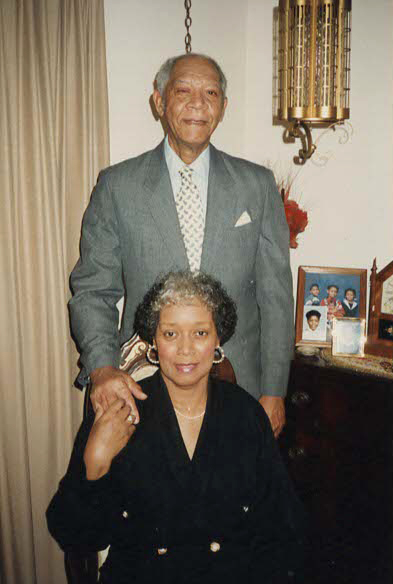

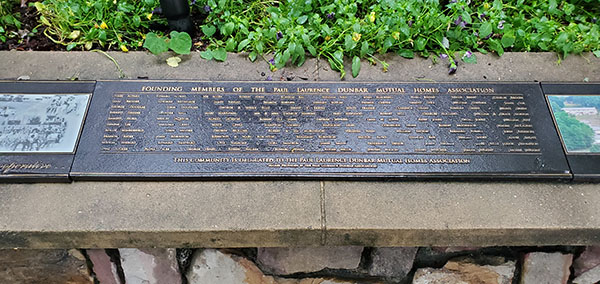

In the early 1950s, Lance Newman and Michael Jones were both children living in Hall’s Hill (now High View Park), one of at least eleven Black neighborhoods that were created during the Civil War era in Arlington. In interviews, they remember Hall’s Hill at that time as a tight-knit and self-sufficient community.

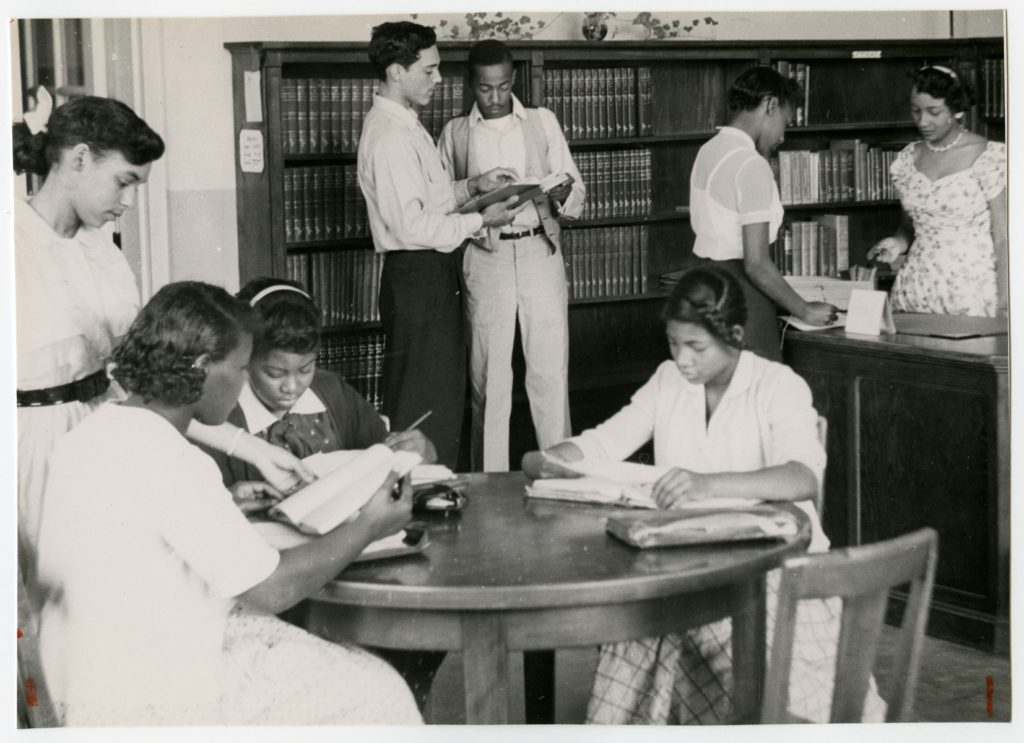

Newman, who lived on Lee Highway, said it was “a great place to grow up” where “everybody knew everybody.” Jones grew up on Emerson Street and, like Newman, attended John M. Langston Elementary, which served Black students in the community under segregation.

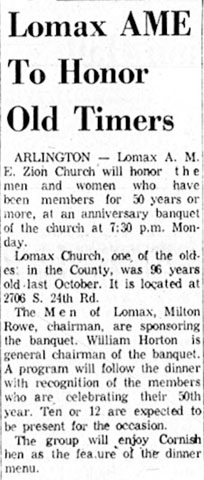

In 1959, Jones and Newman became two of the first four Black students to desegregate Arlington Public Schools when they enrolled in Stratford Junior High, along with Hall’s Hill residents Ronald Deskins and Gloria Thompson.

Ad for Halloween costumes and candy at Clarendon’s G.C. Murphy, a five and dime store. Daily Sun, vol. 16, no. 155, Arlington, Va, October 18, 1951.

In his oral history interview, Jones explains how segregation shaped the environment of Hall’s Hill and the lives of those who lived there. He described Hall’s Hill as “a self-contained community,” bounded by a seven-foot-tall segregation wall, which included the neighborhoods of Fostoria and Waycroft.

Constructed from wood and cinderblocks on an individual home-owner level, the entirety of Hall’s Hill was quartered off in the early 1940s with only one entrance and exit. “There were no connecting sites to the other communities of white families around there,” Jones said. “Once you get into the Black community there, you had to come out by the way you came in.”

Candy apples and other Halloween treats pictured for a recipe article in the Daily Sun. Vol. 17, no. 95, October 16, 1952.

Because of the restrictions that Jones and Newman experienced as Black children under segregation, Halloween offered an opportunity to cross the physical and invisible boundaries between their world and the world “outside” Hall’s Hill.

Disguised in masks and costumes, they could trick-or-treat in their own neighborhoods as well as in the white neighborhood. The goal was to get as much candy as possible – but the “trick” was to not eat it all in one sitting and get sick!

Lance Newman: Every Halloween, we’d go trick-or-treating, and we used to go up to what we called the white section up there—22nd Street, across George Mason Drive—because they were the only ones that gave us tons of candy. Anyway, you know. Kids have masks on, and the people were pretty—and that was a big thing when you were in the second, third, and fourth grade for trick-or-treating, and we just went—you know. That was another thing that’s different today. Nobody lets their—if you were at that age, you let your kid go alone for pretty good reasons. But you did it in groups, and so that was a fond memory from my experience.

Michael Jones: Halloween was great when I was growing up, because Halloween, because of the masks and the outfits, you couldn’t—you didn’t have to just trick-or-treat in your own neighborhood. Of course, you did—if you put on a good outfit, you could go outside to the white neighborhood and go trick-or-treating, because they wouldn’t know who you were if you had your mask on. So, you could go instead of—if you didn’t get enough candy in the Black neighborhood, you go outside to the white neighborhood and get it. And the one thing—you get those big shopping bags—you know—those bags like you get at Whole Foods—stuff like that—and full of candy. After a while, you grew up, you learned you couldn’t eat all your candy in one night or you’d get sick. You had to put it aside, so it was bountiful once—you know. I guess I learned once I—I guess once I get into Stratford or something—elementary—a little above elementary-school age—where to go for Halloween and things like that. But otherwise, it was—Halloween was great.

A Halloween-themed ad for Alexandria Dairy. Daily Sun, vol. 21, no. 76, Arlington, Va, October 25, 1956.

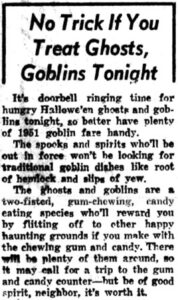

Daily Sun, vol. 16, no. 165, Arlington, Va, October 30, 1951.

For Jones and Newman, trick-or-treating with friends and enjoying the spoils for days (or hours) afterward was their fondest memory of Halloween. Do you have any memories of trick-or-treating in Arlington, or celebrating holidays in Hall’s Hill? We want to hear from you in the comments!

Works Cited

- Lindsey Bestebreurtje, “A View from Hall's Hill: African American Community Development in Arlington, Virginia from the Civil War to the Turn of the Century.” Arlington Historical Magazine. 2015.

- Mark Blitz, “Once There Was a Segregation Wall in Arlington.” Arlington Magazine. June 1, 2020.

- Michael Jones Interview. Arlington County Public Library, Oral History Project. 2016.

- Wilma Jones, “24 Years is a Long Time to Desegregate.” Arlington Virginia History…From the Black Side (Blog). July 19, 2020.

- John Paul Liebertz, A Guide to the African American Heritage of Arlington County, Virginia.

Arlington, Va: Dept. of Community Planning, Housing and Development, Historic Preservation, 2016. - Lance Newman Interview. Arlington County Public Library, Oral History Project. 2016.

Related blogposts from the CLH

Help Build Arlington's Community History

The Center for Local History (CLH) collects, preserves, and shares resources that illustrate Arlington County’s history, diversity and communities. Learn how you can play an active role in documenting Arlington's history by donating physical and/or digital materials for the Center for Local History’s permanent collection.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

Center For Local History - Blog Post Message Form

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields

![[Holmes Branch Library] Exterior of the Holmes branch of the Arlington Public Library system. 1946, 1 print, b&w, 8 x 10 in..](https://library.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/29-0046p6-scaled.jpg)

![[Interior of the Holmes Branch Library] A librarian and two children inside the Holmes Branch of the Arlington Public Library 1946, 1 print, b&w, 8 x 10 in..](https://library.arlingtonva.us/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/29-0359p6-scaled.jpg)