Celebrate the Fourth of July with books about Independence Day, the people who made it possible, the symbols we use to celebrate, and thoughtful explorations of what it means to be American.

(tap image to view book list)

The Center for Local History reflects on the passing of Ronald Deskins, a pioneer of the Civil Rights movement in Arlington County.

At the young age of 12, Ron Deskins played a crucial role in integrating Virginia public schools. On Feb. 2 1959, Deskins, along with classmates Michael Jones, Gloria Thompson, and Lance Newman, entered then all-white Stratford Junior High in quiet but determined defiance of Virginia Senator Harry Byrd’s policy of Massive Resistance.

This historic moment – often referred to by the press at the time as “The Day Nothing Happened” owing to the lack of violence – is now marked by banners at Dorothy Hamm Middle School, housed since 2019 at the original site of Stratford Junior High School.

"I was pretty nervous that first day," Deskins said at a 2016 tribute to the actions taken in 1959. He went on to mention that a few students "made it their business to make our lives miserable…They were not successful…Although they called us plenty of names."

Three police officers stand at the entrance to Stratford Jr. High School as the four black students enrolled in the previously all-white school arrive for classes in Arlington, Va., on Feb. 3, 1959. One of the officers records the scene with a movie camera. Approaching the entrance are, left to right, Lance Newman, 13, Ronald Deskins, 12, Michael Jones, 12, and Gloria Thompson, 12. (AP Photo)

Edward Hummer, a fellow Stratford and W-L student, interviewed Ronald Deskins for induction into the W-L Athletics Hall of Fame in 2018. At the time, Deskins was volunteering at a public library in Berryville, VA. Hummer recalled the experience of speaking with Deskins about his life:

“I was struck when I read about his very first reaction upon entering his first classroom...The four black kids were taken in a rear door to escape the throng at the front door…the other kids in Ron's homeroom were already seated and had been prepared for his arrival. When he was escorted in a few minutes after the bell, all their heads naturally turned to him as he entered. His first thought on seeing all those heads turn his way was to say to himself, "It's just me."

Dorothy Hamm Assistant Principal Lisa Moore remarked that it is "our expectation, for all our students and staff to know this history. The history that took place in this building, they need to know that, and live that."

"Our hearts are devastated," Moore added. "This was a huge loss for our community."

Mr. Deskins’ self-effacing manner was typical of his attitude towards his accomplishments and the contributions he made during his lifetime, including his role in the integration of the Fairfax County Fire Rescue Department. Mr. Deskins was the fifth Black firefighter employed by Fairfax County and he helped establish Northern Virginia Minority Firefighters Combined. He eventually achieved the rank of Captain and retired after 34 years of service.

Edward Hummer remembers the man who thought of himself as just me as “quite a guy. It was a great pleasure and a great honor for me to get to know him so many years later when he was inducted into the W-L Athletic Hall of Fame. I am greatly saddened by his death.”

The Center for Local History (CLH) at the Arlington Public Library collects, preserves and shares historical documents that tell the history of Arlington County, its citizens, organizations, businesses and social issues.

The CLH’s Community Archives includes thousands of pages of material related to the desegregation of Arlington Public Schools, and makes these materials available to students, researchers, scholars, authors, teachers and the community.

To learn more visit the Project DAPS website and read the 2018 blogpost, The Desegregation of Arlington Public Schools.

Because there are always more layers of history to find and examine, the CLH continually seeks community donations and oral histories; use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History or contact us at localhistory@arlingtonva.us.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields

Milton Isiah Rowe, Sr., (1925-2016) was born in Washington, D.C., to Hester and Isiah Rowe. His family moved to South Arlington, a community where they had longstanding family ties, in 1927, when Rowe was a young child.

With this move, Milton Rowe began his long life as a Green Valley resident. Over the next 89 years he served in many community and civic roles across the County, and became part of an Arlington legacy.

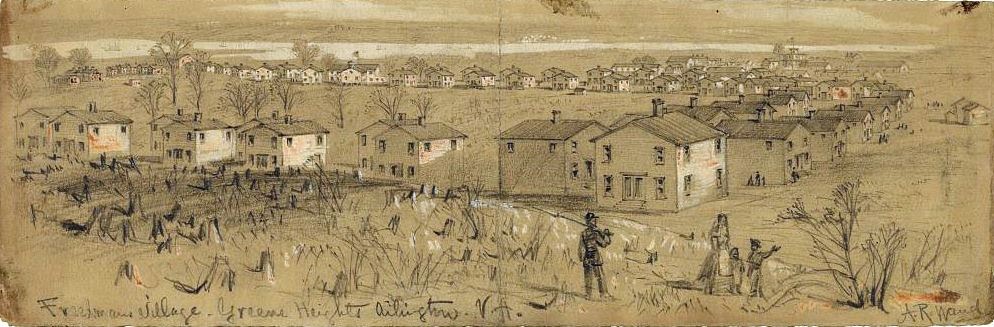

Milton Rowe's great-grandfather was William Augustus Rowe (1834-1907), a pivotal figure in the early development of the Green Valley neighborhood. William Rowe had been born enslaved, and later escaped to Freedmans Village in Arlington.

Freedmans Village was established in 1863 on land seized from Robert E. Lee and occupied by the Union Army during the Civil War and became a thriving community for freed slaves.

Artist representation of Freedmans Village, circa 1864.

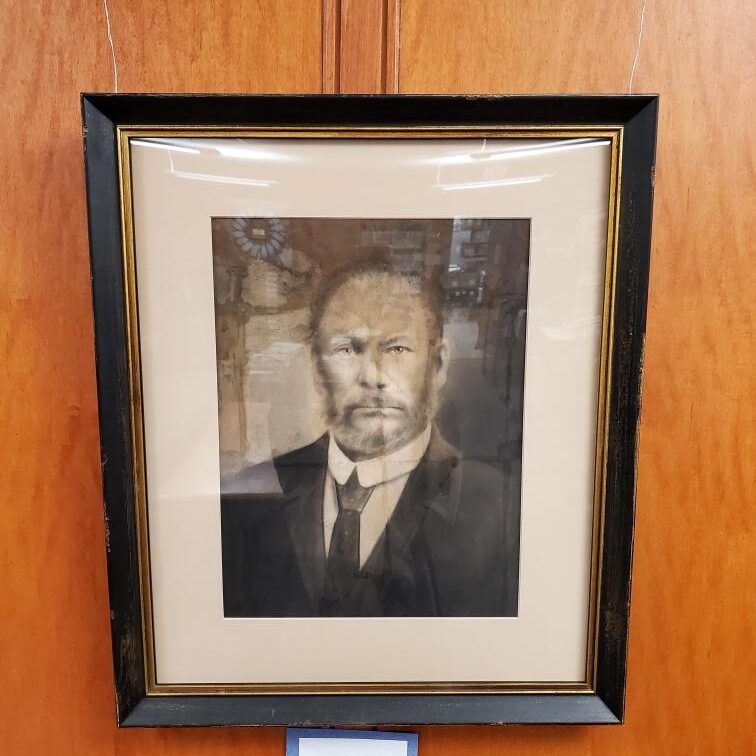

William Rowe first trained as a blacksmith and later served in numerous civic roles, including as the first Black member of the Board of Supervisors and Arlington District Board Chairman.

Learn more about William Augustus Rowe in our blogpost from March, 2021.

A portrait of William A. Rowe currently hangs in the Center for Local History.

Milton Rowe first attended Kemper Elementary School in Green Valley. At this point, Arlington’s public school system was still segregated. Kemper was the school designated for Black children, and had opened in 1875 within Lomax A.M.E. Zion Church.

By 1893 the school had moved into a new brick, two-story building constructed by Noble Thomas, the first Black contractor in the County. Hoffman-Boston School was the only secondary school available to Black children in Arlington, and many chose to commute outside of the County for educational options.

Rowe attended Garnet-Patterson Junior High School and Armstrong Technical High School in Washington, D.C., for his secondary education. Armstrong was one of only two high schools open to Black students at the beginning of the 20th century

After high school, Milton Rowe went on to work at the Pentagon and subsequently enlisted into the Coast Guard, where he served on the USS Pocatello during WWII.

Upon his honorable discharge, Rowe returned to the Arlington area to work at the Pentagon and on March 31, 1945 married Ruth Mae Robinson, who also worked at the Pentagon as a typist. They were married in Lomax A.M.E. Zion Church, the church William Rowe and his wife Ellen helped organize in 1863 and where William Rowe had also been an early member.

Ruth and Milton Rowe went on to have four children – Gloria, Milton, Jr., Elroy and Brian (as of June 1, 2022, there are 2 daughters-in-law, one son-in-law, 12 grandchildren, 11 great grandchildren and 3 great, great grandchildren).

In 1995, Milton and Ruth celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary. Ruth died in 2004.

Milton and Ruth Rowe were early owners of a home in the Paul Dunbar housing community in Green Valley, a wartime housing unit for Black residents built in 1944 by the Federal Public Housing Authority. They featured 15 masonry buildings with 86 units.

The Dunbar Homes were one of two major housing cooperatives established during the war, along with the George Washington Carver Homes. After the war, Black residents pooled their resources and bought the housing complexes, establishing the first two Black-owned housing cooperatives in the country. The Dunbar Mutual Homes Association maintained the property until 2006, when it was demolished.

In 1955, the couple built and relocated the family into a home near the Army Navy Country Club in south Arlington.

A historic marker celebrating the original members of the Paul Lawrence Dunbar Mutual Homes Association is located at the corner of Shirlington Road and South Four Mile Run, across from the W&OD Trailhead.

Rowe retired from the Pentagon after 37 years of service with the army, receiving many letters of commendation for his outstanding performance of duty.

He continued his career as a professional butler, a second job he held throughout his working life.

In this role, he worked at various embassies and the home of Robert F. Kennedy in McLean. There, he remembered meeting John F. Kennedy, whom he once loaned a pair of boots to on a snowy Virginia day.

Rowe also served at numerous events at the White House, where he met many of the presidents of the 20th century.

Milton Rowe was active in the Green Valley community and served on the Trustee Boards and various committees at Lomax A.M.E. Zion.

He was also a member of the Nauck Citizen’s Association (now the Green Valley Civic Association), the Arlington Housing Committee, the NAACP, the Y.M.C.A., the American Legion, and several seniors’ groups. He was also an advisor to his sons’ Boy Scouts Troop #589, which has a historic legacy as one of the first local scouting groups for Black children, established in 1952 by Ernest Johnson.

A February 17, 1962, Northern Virginia Sun article mentions Milton Rowe’s role as chairman of the Men of Lomax organization, along with details from a church event. Newspaper image courtesy of Virginia Chronicle.

In 2010, NBC reported on Milton Rowe in a feature about the legacy of Freedmans Village on the grounds of Arlington National Cemetery. The cemetery was constructed on the grounds of Freedmans Village, which had been closed by the government in the 1890s to make way for the burial grounds. The closure of Freedmans Village displaced the nearly 1,000 Black residents who had made their homes there. No markers exist to commemorate the freed slaves who had once lived on the land.

Milton Rowe’s life touched many important parts of the County’s history, and his legacy lives on through his many achievements and experiences that made him a pillar of both Green Valley and Arlington at large.

Learn more: Milton Rowe is featured in Dr. Alfred O. Taylor’s book “Bridge Builders of Nauck/Green Valley: Past and Present.”

The Center for Local History at the Arlington Public Library collects, preserves and shares historical documents that tell the history of Arlington County, its citizens, organizations, businesses and social issues. The CLH operates the Research Room at Central Library and the Community Archives program.

Because there are always more layers of history to find and examine, the CLH continually seeks community donations and oral histories.

Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History or contact us at localhistory@arlingtonva.us.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields

Our theme this year is Oceans of Possibilities.

Dive into new depths of reading and programs, join Potomac Conservancy in their fight for clean water, and win tickets to Washington Nationals Games!

Pride Month is celebrated each year in June, to recognize the impact that LGBTQIA+ individuals have had on our history - locally, nationally and internationally. Learn more from the Library of Congress.

A note about LGBTQIA+ These letters stand for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex and Asexual. The + sign in this context recognizes that our understanding of labels and vocabulary is personal, and continues to evolve.

{{ e.description | plainText | trunc(descMax) }} [see more] RSVP

Oral histories are used to understand historical events, actors, and movements from the point of view of real people’s personal experiences.

The life of long-time Arlington resident Gertrude "Trudy" Ensign was recently memorialized at Clarendon United Methodist Church. Born October 4, 1920 on a farm in southwest Iowa, Ensign left Iowa to take a job with the Army Security Agency (a precursor to the NSA) during World War II, settling in Arlington, where she lived until her death on February 28, 2022.

In November 2017, Ensign recorded an oral history with the Center for Local History. She spoke about her work during the war, as well as life in Arlington.

In this excerpt from the oral history, she talks about her work during the war. While not a code breaker herself, Ensign worked in Army communications.

Col. Mosser presents Mrs. Gertrude C. Brown (Ensign) with an Outstanding Performance Rating Award on 30 March, 1971 at Arlington Hall Station (from reverse of photo)

Narrator: Gertrude Ensign

Interviewers: Judith Knudsen

Date: November 6, 2017

INTERVIEWER: Well, when you say there were people there, they were cracking Japanese code. That was not your job.

NARRATOR: Yes. Not my job.

INTERVIEWER: So what codes were you getting? Were you getting the codes that had been cracked, and then you had to encipher with the—

NARRATOR: Okay. This is the part that I think we have to understand, that none of this could happen if we didn’t have field stations.

INTERVIEWER: Okay.

NARRATOR: Because that’s where our intercept came from. Like Vint Hill Farm was an intercept station, and they had a whole field of antennas up out in the field. There were field stations in the Pacific, and there were field stations in Alaska. I think there were some in Europe, too. It made sense. If not field stations, then they had some other options. Maybe they had direction-finding stations, which, you know, you have a unit with direction equipment, maybe 180 degrees, and if you all were pointing at this thing, then you would be able to intercept—find a station, an enemy station you were looking for, and be able to intercept them.

INTERVIEWER: Okay.

NARRATOR: And if you could do that, then you could identify the location, because you were getting the signals from different locations based on where you were. So that was really the part that—our part of what happened at ASA [Army Security Agency]. I mean, we knew that there was a whole building called B Building where they were trying to break the codes. But that was not any of what we were concerned with. When the codes were broken I guess they went wherever they were supposed to go, which would have been, you know, teletyped there someplace else. But anything that we—most that we handled was administrative and keeping the field stations open and things like that. After the war we probably had more like regular communications, because we’d have the commanders of the different field stations come back in. At that point I had moved to a different job, because when—during the war there was no question about you having a job there. But when the war was over, one of the bosses came out to me one day and said, “You know, the war’s over, and the boys are coming back. They said there’s a gentleman here in the area that has the same qualifications you do, because he worked in the field during the war. And he has a promote—he can take your job,” in other words. But they said, There’s a job open down in what we call GAS50, and you can go down and apply for that job. Well, it sort of took me by surprise, of course, but that’s exactly what I did. That job then, the gentleman that interviewed me said, “Well,”—I think I was a GS6, 00:11:00 and he said, “You’ll have to take a break to a GS5.” But then he said, “When you get your promotions, it’ll be a GS5-7-9-11-13,” and so that’s what I did then. So when I retired I was GS13, which was a very nice grade.

INTERVIEWER: Yes, it is a very nice grade.

NARRATOR: It left me a very nice income.

The goal of the Arlington Voices project is to showcase the Center for Local History’s oral history collection in a publicly accessible and shareable way.

The Arlington Public Library began collecting oral histories of long-time residents in the 1970s, and since then the scope of the collection has expanded to capture the diverse voices of Arlington’s community.

To browse our list of narrators indexed by interview subject, check out our community archive. To read a full transcript of an interview, make an appointment to visit the Center for Local History located at Central Library.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share?

Use this form to send a message to the Charlie Clark Center for Local History.

Do you have a question about this story, or a personal experience to share? Use this form to send a message to the Center for Local History.

"*" indicates required fields

In 1978, a joint congressional resolution established Asian/Pacific American Heritage Week.

The first 10 days of May were chosen to coincide with two important milestones in Asian/Pacific American history:

In 1992, Congress expanded the observance to a monthlong celebration, now known as Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month.

(Source: Census.gov blogpost: Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month: May 2022)

Explore over 20 hand-picked book lists for all ages and interests, featuring fiction and non-fiction titles by contemporary authors. Topics range from history and politics to civil rights, from picture books to graphic novels, sci-fi, romance, mystery and more.

{{ e.description | plainText | trunc(descMax) }} [see more] RSVP

Writer Kim O'Connell takes us on a journey through a part of Clarendon once named "Little Saigon," drawing on her personal story to tell part of Arlington's history.

The project, “Echoes of Little Saigon,” was made possible with a generous grant from the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities (VFH) and support from Arlington Cultural Affairs, a division of Arlington Economic Development; Arlington’s Historic Preservation Program in the Department of Community Planning, Housing and Development; and the Arlington County Library’s Center for Local History. Read Kim's writing on her website.

Looking for something to read while you are waiting online or at bus stop? Get instant access to current and back issues of some of your favorite magazine titles via Flipster.

Use the app to read on the go: includes People, Sports Illustrated, Real Simple and the Atlantic.

The final day to donate is Friday, April 15, after which all items will be boxed and secured for shipping.

The Northern Virginia Regional Commission (NVRC) has organized a campaign to collect donations of much needed cold weather items for the more than 3 millions residents of Ukraine who have fled their county due to the Russian invasion.

Items to donate:

In Arlington, items can be dropped off at Central Library. The donation box is next the Quincy Street entrance, under the bulletin board near the Youth Services room.

Learn more about the Northern Virginia Regional Commission, including more places to drop off donations, on the NVRC website.

Libraries and librarians nationwide play a vital role in transforming lives and strengthening communities.

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom recently issued a statement opposing widespread efforts to censor books in U.S. schools and libraries.

Unfortunately, Virginia has been subject to these censorship efforts, and in light of this, Arlington Public Library is taking a stand to build awareness of these challenged books.

Stop by your local branch between April 3-9 and explore our collection. Pick up a free coffee and a challenged or banned book (while supplies last).

We champion the power of stories, information and ideas.

We create space for culture and connection.

We embrace inclusion and diverse points of view.